Above the mahogany gun rack in my grandfather's house hung a shadow box with a small stack of colorful money that fanned out of a leather wallet. There were fives, tens and 20s, but the numbers printed on the bills were so far removed from any actual value that their previous owner had chosen to frame them as keepsakes. These were Confederate bills, and the South wouldn't be rising again.

The bills had found their way into my grandfather's house past inflation and eventual irrelevance at the end of the Civil War, through Reconstruction and the slow rekindling of the Southern economy. If my grandfather was to be believed, the bills belonged to his great-great-granddaddy, a man who fought for the Confederate States of America, was decorated in combat, captured and held prisoner, and then freed after the end of the war with nothing but a blanket to shelter him as he walked the long miles barefoot back to South Carolina.

This story, I've found, is a common one among many Southern families, and while I'm sure there were a few blanketed ex-Confederates straggling back home after the treaty at Appomattox, I think this story is more to make the descendants of a failed nation state feel a bit warmer toward their great-Uncle Johnny Reb.

The facts themselves are a bit tougher to swallow. South Carolina, the state in which I was raised, quite literally started the Civil War, ratifying the Articles of Secession and punctuating it with cannon fire in Charleston Harbor towards an island fort occupied by the Union. That first battle, as South Carolinians are quick to point out, resulted in only one casualty—a horse. But the implications ran deeper. Union General Sherman famously said in response, " … When I go through South Carolina it will be one of the most horrible things in the history of the world. The devil himself couldn't restrain my men in that state." Sherman eventually burned Charleston to the ground. And the havoc and destruction from that first declaration of war and rebellion crept all the way into my childhood one century later.

We took elementary-school field trips to see grown men re-enact battles on the fields outside of Middleton Plantation. We studied the relics in the medical tent and imagined life as young amputees. We wrote reports on the men encamped outside a war zone, ready to lead the charge. Fantastic words like "hard tack," "submersible," and "grape shot" invaded our vocabularies. That all of my Social Studies classes spent months on their Civil War sections made sense to me: It is a war that is still being fought.

And it's not just fought by costumed re-enactors. I'm still fighting with it, too.

My grandfather told me another story about my family's past, one that's told a lot less frequently than the Reb-in-swaddling-clothes myth, so I fear it’s true. There's no easy way to say it: My family owned slaves. Some great-Aunt far down the line kept about a dozen African slaves on her small plantation outside of Florence, South Carolina.

Much of me didn't want to know. I ran away from this truth as swiftly as I ran from the South, first to Michigan, then to California. I studied African-American history, praised Malcolm X and affirmative action, tried to deny and to forget. I called for South Carolina to remove their Dixie flag from the capitol building as swiftly as I had removed the traces of an accent from my voice, to the annoyance of my Southern family. But still the guilt remained.

Penniless after the war, my family moved inland to work on the canals cutting through the capital, Columbia. In 1949, they opened a small, open-air market near their home and began selling fireworks. Twice each year, I make the journey back to South Carolina to sell gunpowder with my family. But much of my time is spent in the fireworks store—my sight of the South was limited to trips to the import warehouses and hardware stores. This year, I was determined to stare down the South I had been ignoring, to confront the past I didn't want to acknowledge.

Seeking the source, I headed to the Confederate Relic Room in the basement of the SC State Museum. I was expecting a small room with a few glass cases, curated by an old lady wearing an antebellum dress. The receptionist, who wore a bob hairdo and a Christmas sweater behind a large desk, looked like she hadn't seen anyone remotely interested in the War in a long time. She waved me inside with a free admission.

What I got inside was more of an actual museum—filled with writing, quotes, exhibits, mannequins, artifacts and relics of all kinds. It wasn't a scattershot collection. This was how the people of South Carolina chose to officially remember the war. From the inscription at the opening of the exhibit hall:

"As the birthplace of secession in 1860, South Carolina stood as the very embodiment of Southern martial spirit, pro slavery and states' rights politics, and resistance to federal authority. Because of its leading role in forming the Confederacy, South Carolina was also a special target of vengeful Union armies, especially in 1865, leading to the dark time of the state's post-war era."

The museum had a lone display case on slavery. It was filled with paperwork, ledgers with prices listed next to names in perfect calligraphy. The display made sure to note that not all slaves worked for free, but neglected to emphasize that they didn't have much of a choice in the matter either way. Iconic photos of slaves weren't shown. The only artifacts of slave life were two bronze identification tags, listing number 231, a male, and 294, a female.

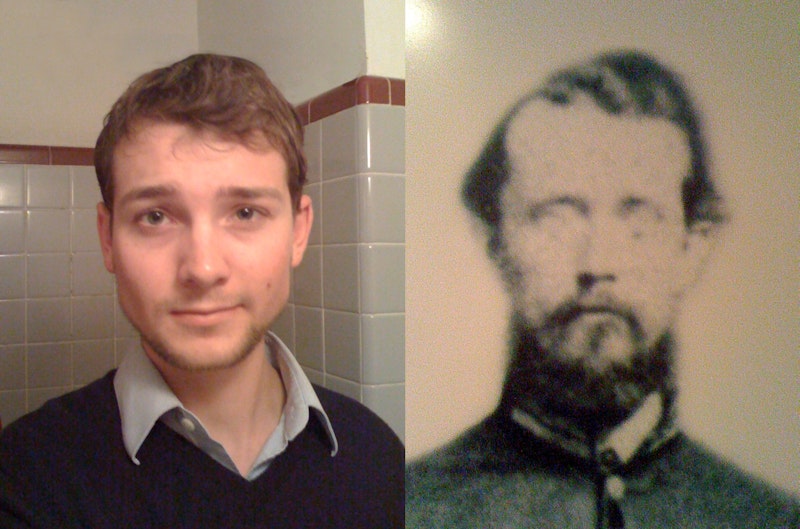

Another exhibit told stories of the revelry in Columbia that followed the signing Articles of Secession. A jubilant citizenship set off canons and made bonfires. "Firecrackers exploded in the street." I saw echoes of myself in the face of an unnamed soldier pictured next to the exhibit. I saw my family of a century earlier, shooting fireworks to celebrate a document that would unravel a nation.

And I hoped that the fires that burned Charleston and made worthless the bills above my grandfather's gun chest also cleansed me of this original sin. I prayed for it to be so, and for forgiveness.