Not long after 1936, the United States was invaded and almost conquered by the Purple Empire. Having already overwhelmed most of Europe and established bases in Canada, the Germanic aggressors killed the entire population of Maine in a gas attack and struck south to take New York and New England. From there, Purple Emperor Rudolph I was unstoppable—or would’ve been, if not for master tactician and spy Jimmy Christopher, code-named Operator No. 5. Thanks to him, Americans fought back, regained their independence, and defeated the Purple Empire.

It’s a great story, even if it didn’t happen. Operator No. 5 was a hero in the pulp magazines of the 1930s, alongside Doc Savage, the Shadow and the Spider. Every month, armed with a trick rapier that coiled inside his belt, Jimmy Christopher fought off would-be conquerors of the United States aided by twin sister Nan, lady-love crusading journalist Diane Eliot, scrappy youngster Tim Donovan, andothers. Frederick C. Davis created the character and wrote 20 issues before the grind of inventing new fictional nations to threaten the USA became too much. He handed the reins to veteran pulp writer Emile C. Tepperman with issue 21, Raiders of the Red Death, and Tepperman found a radical solution to that particular problem.

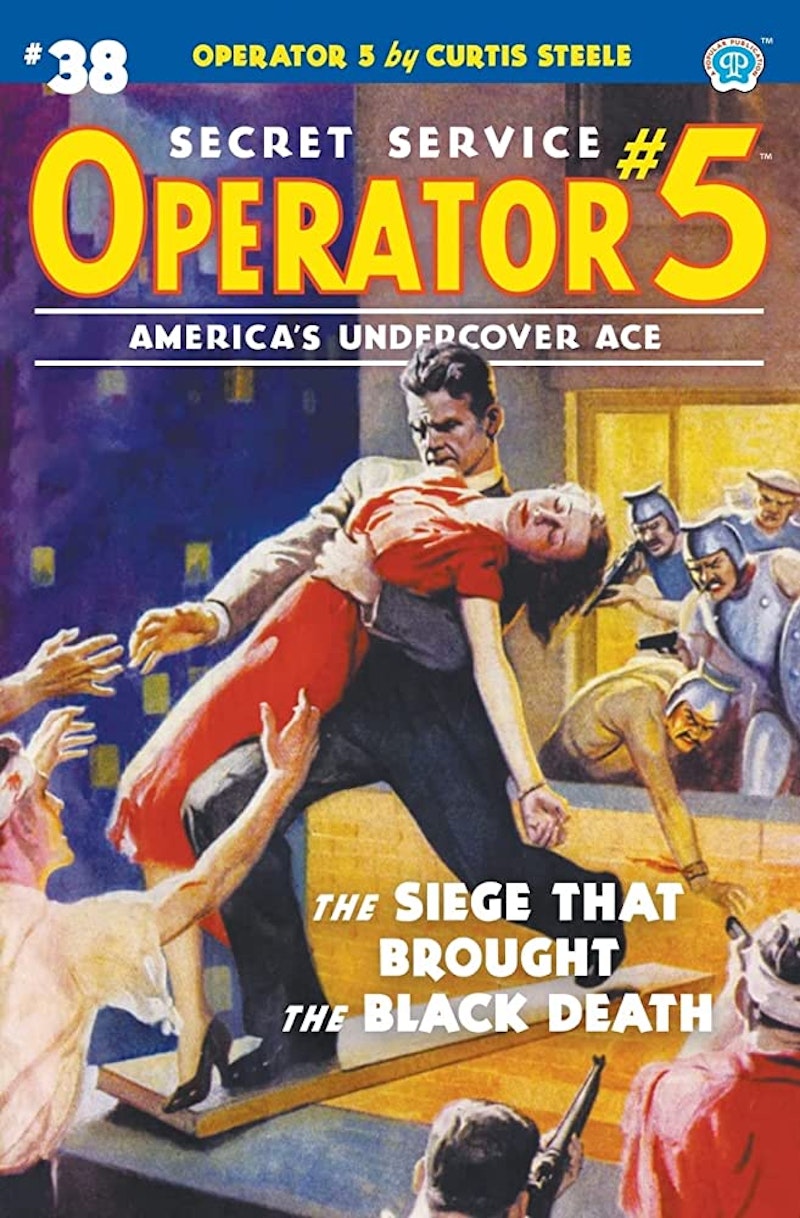

Starting with issue 26, Death’s Ragged Army, he began a multi-issue storyline which opens with Jimmy Christopher as a spy and saboteur behind enemy lines in occupied New York City. Over the course of the saga Christopher rallies American troops, arranges a new air force, liaises with a force of doughty Canadians, and oversees the longstruggle against the Purple Empire. Pulp hero tales were almost always completed in a single volume, but this one sprawled on through 13 issues, up to The Siege That Brought the Black Death in June of 1938—with a 14th issue, Revolt of the Devil-Men,as a follow-up in which Christopher and friendsrebuild their shattered country.

The story’s been called the War and Peace of the pulps, and it’s still a blast to read. Tepperman’s prose is smooth and hyperbolic, vigorous and energetic and over-the-top to exactly the right degree. It’s not sophisticated, but sentence and paragraph structures vary enough that it’s never monotonous. And while this isn’t writing that relies on subtlety or detailed character-drawing, there are jaw-dropping depictions of war and the imagined occupation of the United States, as familiar places become sites for major battles and foreign castles are built in NYC.

There are berserk action sequences—sword fights on top of moving trains, aerial dogfights, desperate battles in imperial throne rooms, color and chaos and high adventure. But you can also see Tepperman experimenting. He develops the idea that the books are being written by a historian in some distant future, and as the series continues he uses that concept to bring in exposition and catchreaders up to date. It’s a striking science-fictional perspective that builds up the reality of the books and also sets them apart from the real world of the 1930s.

More immediately, the books are full of strange images of a battle-torn America reverting to medieval times. The war’s so savage fuel and technology are used up. Phones become unusable, electricity rare, and swords and catapults return to the battlefields. Leprosy and the Black Death spread. By the end of the series, a Mongol hordesweeps across Pennsylvania toward Valley Forge.

It’s tempting to view the series as foreshadowing the Second World War, not least because the Purple Empire is German-speaking with mostly German names and a stylised logo. But this is wrong. Tepperman couldn’t imagine the future, and there’s even a mention of America staying out of a Second World War. Instead, the imagined invasion echoes World War One and the Civil War. Sometimes a modern reader’s wrong-footed by that look backwards; when you read about the Purple Empire using advanced new aircraft, you can’t help but imagine jets. But then you realize these are only more efficient biplanes, just as the gas that obliterates Maine is less an anticipation of nuclear bombs and more an enhanced version of mustard gas.

There’s a consistent idea across the novels of America and what it means to be an American—or what it meant for Tepperman. There’s an insistence on freedom, and an American desire to fight for freedom. A sense also that America’s struggling not just with a European empire, but a European past, with monarchy and medievalism. The books focus almost entirely on white Americans, and if that’s an outdated perspective, it does create a sense of America fighting a specifically European ideology that birthed it and threatens to strangle it.

The patriotism in the books is uncomplicated but also old-fashioned, looking back to the Minute Men and Valley Forge and a set of images not often evoked today by either side in America’s current culture war: an America of yeoman farmers, not titans of industry. It’s an egalitarian ethos; Tepperman shows women as soldiers, fighting and dying in front-line combat alongside men, driven by the same patriotic ideals and commitment to freedom.

Mainly, though, these books provide action thrills on a previously-unimagined scale. The overallstructure holds together surprisingly well, though the end’s somewhat abrupt and the follow-up book feels aimless after the epic’s concluded. Still, itworks, a thrill ride in prose with lots of excitement,terror and fun. It’s surprising it hasn’t been revived in some way. You could easily imagine it adapted into a season-long Netflix show. But the story’s also perfect just as it is: the most epic of all pulp adventures.