I grew up in a family possessed of a ruin in progress, an antique set of Anker-Steinbaukasten, the classic German toy building blocks. Never sequestered as precious heirlooms, roughly rubble-piled in a rude, unoriginal corrugated cardboard carton, the stone blocks were at least old as my grandmother and impossible to imagine new on a toy shop shelf as granny teething a binky.

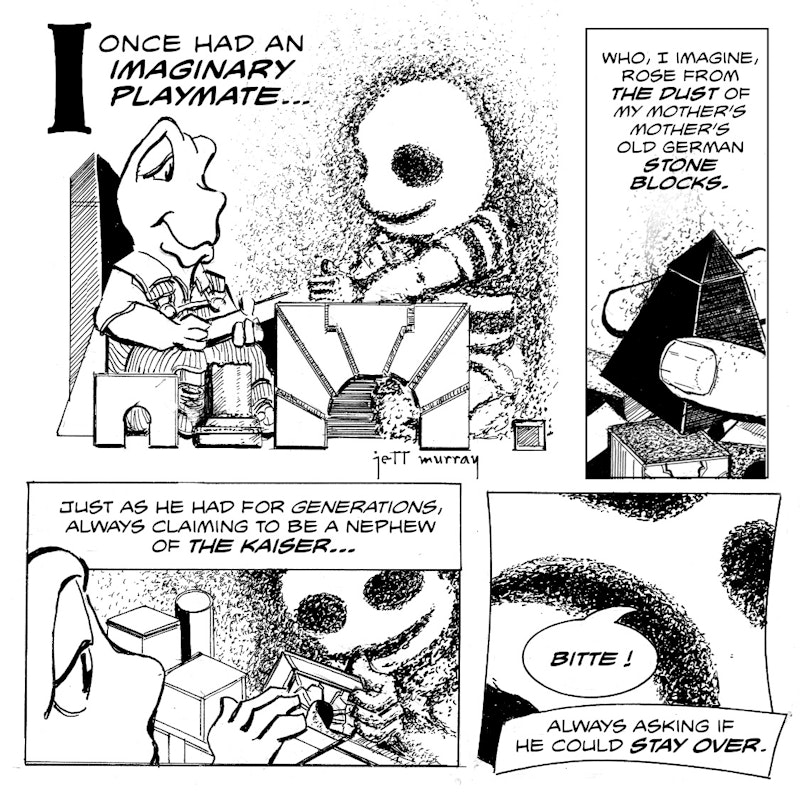

Forever old, forever there. Their strange domestic presence latched on and never let go. Much later, as a cartoonist, inspired by the household spirit Odradek in Franz Kafka’s story “Cares of a Family Man,” I portrayed the blocks as haunted by a ghostly self-styled nephew of the Kaiser.

Manufactured since 1880, inspired by Friedrich Froebel’s early minimalist wooden kindergarten blocks but rendered realistically in the manner of old European masonry, Anchor sets are still marketed today at fancy-pants prices. Yet through no fault of their own, the new blocks lack the tumble-down charm of my family's broken-in set, wonderfully melancholic after three or four generations of wear and tear.

Can’t recall when my mom first hauled them out. Seemed like they were always around, without sentimental backstory, just there, matter-of-fact as a coat hanger, paradoxically out of place as a chunk of medieval cathedral at the bottom of a bedroom closet. The eroded, decomposing columns and arches and keystones and obelisks and pedestals and still other shapes that exceed my architectural vocabulary and couldn’t be more persistently memorable.

Fair into middle age I caved into temptation knowing better. Killer bee lodged in my bonnet, I checked out contemporary Anchor blocks at a Massachusetts Ave. egghead game and toy shop between Harvard and Central Squares in Cambridge.

Didn’t take long. My unreasonable expectations and I walked out in a brown study predictable as croaking and capital gains. These weren’t my toys and couldn’t be, any more than I could step in the same Charles River twice.

Anchor blocks are real stone, cultured from the stuff of beaches and golf ball traps, quartz sand. The clever, likely proprietary process behind the blocks’ manufacture involves mixing sand and chalk and traditional masonry colors with linseed oil, and then molding and baking precisely to shape.

The kicker was, how artfully my family’s Anchor collection partially and artfully crumbled, over two world wars and several lifetimes of water over the dam. As such, the blocks beggared comparison with any construction toy of my mid-century modern experience. New, they might be appreciated simply as a cut above Legos, Lincoln Logs, Tinker Toys and Erector Set mechanical kits. But authentically roughed-up just-so like a proper Pre-Columbian fake, they suggested provenance to burn. Their talismanic, eerily evocative geometries, charged with the imaginations of children who were my ancestors, were the strangest attractors for me, albeit nothing I’d ever have thought of as romantic, my only sense of the term at the time being hearts, flowers and mush.

I discovered my attraction wasn’t universal. When I had friends over, I tried mashing-up the Anchor blocks with our house set of steroidal,minimal, solid maple, then-educationally fashionable Neo-Froebel blocks with limited success.

The new, heavy-lift lumber was a crowd-pleaser and went with plastic army men like tonic with gin. We built living room rug forts of grand scale, arrayed with molded machine gunners, grenade throwers, snipers and minesweepers, a nebulous war game that might include an imaginary King Kong or Godzilla at the gate, pretext to wreck what we just constructed. For that, no matter how cyclopean, how much you squinted, how many bazooka guys lined the walls, whatever we built looked like kids’ stuff compared to my vintage stone blocks.

At least they did in my mind’s eye.

My buddies grudgingly allowed that one stone block shape was cool, once I pointed out the smooth black pharaonic obelisks reminded meof nuns. That got traction. While nuns didn’t fly or sing back then, no toy soldier brought so much spooky to the battlefield. So, as a force multiplier we posted stone “nuns” between bazooka guys on the wall to put the whammy on the invisible monster, or the flavor of Axis enemy du jour at the gates.

For that, nobody aside from younger siblings paid much attention to our Anchor blocks. And I lacked the vocabulary, the history, and the elevator pitch to close the deal. I couldn’t say, “Doesn’t this worn-away Roman arch look sacked by barbarians? Doesn’t that make you feel like a minor chord?” Come on, I was eight, all right? Didn’t know from Romans beyond Androcles and The Lion on Million Dollar Movie. And minor chords? All I knew was, I liked when Gene Autry sang “Ghost Riders in The Sky.”

All right, our Anchor blocks largely remained an inside family fascination, and that was okay. For a while they were stored at my grandmother’s summer place where the play masonry and I killed a lot time together. I raised ruined sacrificial temples close to active fires in the fireplace. I recall working the temples into an interior cinematic scenario likely inspired by my apocalyptic favorite, “When Worlds Collide.”

Earlier I referenced Kafka’s Odradek, an animate diminutive household entity of which a father speaks ruefully, a spectral presence without precedent or identifiable purpose beyond hanging out, no plaything so much as a ghostly bot playmate, an enigmatic familiar of his children he fears will outlive him, retained by succeeding generations. While I have no children of my own, I wonder if the ancestral stone blocks will continue to benignly haunt some of my siblings’ offspring, and give anyone heavy-hearted pause at this vestige of something that cannot be quite lost or found.

While casually researching Anchor blocks, I accidentally unearthed Pleasure of Ruins written by English novelist Rose Macauley in 1953, a historical meditation on the enduring fashion of architectural decay. Now a must-read for me, if you’re not already familiar and dig my drift, it might bear excavation.