The 2008 Nobel Prize for Literature today went to Frenchman Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clezio, who, like 1997 winner Dario Fo or 2004 laureate Elfriede Jelinek, will be greeted in America with a mild “Wha?”

That the winner is scarcely known in America (there’s only one small-press paperback available on Amazon.com) shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone. A minor skirmish broke out recently when Swedish Academy permanent secretary Horace Engdahl made the following grand claims to the Associated Press:

“Of course there is powerful literature in all big cultures, but you can't get away from the fact that Europe still is the center of the literary world ... not the United States.”

[…]

Speaking generally about American literature, however, he said U.S. writers are “too sensitive to trends in their own mass culture,” dragging down the quality of their work.

“The U.S. is too isolated, too insular. They don't translate enough and don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature,” Engdahl said. “That ignorance is restraining.”

A lot of deserved, righteous indignation erupted in the wake of Engdahl’s preposterous claims. Adam Kirsch—who was the marquee name in one of the country’s best book sections at The New York Sun until the paper tanked earlier this month—wrote in Slate that Engdahl’s comments secure the prize’s illegitimacy. He cited Philip Roth, the acknowledged American frontrunner for the award, as deserving of the prize for his mixture of realism and postmodern experimentation, and for his having edited the important (yet now out-of-print) “Writers from the Other Europe” series for Penguin in the 1970s. “Unless and until Roth gets the Nobel Prize,” Kirsch ends his piece, “there's no reason for Americans to pay attention to any insults from the Swedes.”

Likewise, Charles McGrath repeated the common complaints about the Literature Nobel in the New York Times: a number of the Academy’s ignored writers (Tolstoy, Joyce, Borges, Nabokov, Auden, and Graham Greene among them) are more deserving than many of the winners; the award is too political and more recently, too anti-American (“A US [government] aide told me that he enjoyed my plays. I did not reply,” recounted 2005 winner Harold Pinter in his prize lecture); and that it’s ironic to shun American writers for their supposed insularity.

These are all important points, but they illuminate how poorly defined the criteria for the Literature prize really is. Unlike the other Nobels—economics, chemistry, physics, and the Peace prize—the literature award is not given for a specific accomplishment; it’s something of a lifetime achievement award where occasionally (as in Thomas Mann’s case) a single work is highlighted as especially deserving. Le Clezio, for instance, was selected for being an “author of new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization,” whatever that means. (Another favorite: 1974 winner Harry Martinson, who was cited “for writings that catch the dewdrop and reflect the cosmos.” Indeed.) A writer’s selection has little to do with more easily recognizable measurements like artistic innovation, prolificacy, influence, or esteem within one’s own country.

Additionally, since the Nobel is the most lucrative and longstanding international literary award, it’s commonly thought of as more truly international than it is. Far from being a global consensus, the Nobel is strictly a Swedish award; and while the Swedes are a well-read people, it’s strange that any one country’s judgment, positive or negative, should be seen as the ultimate verdict on a writer’s career.

For all these reasons, I tend to side with Kirsch and say that the Academy’s willful disregard for American literature is indeed proof of their prize’s worthlessness. It’s true that fewer translated books are published and reviewed in America (the Literary Saloon covers this state of affairs rigorously), but that’s a reflection on the publishing and journalism industries rather than on individual writers. Only two American writers, Saul Bellow and Toni Morrison, have won the prize since John Steinbeck (a middlebrow pick if there ever was one) took it in 1962; meanwhile, American literature since that time has been as vibrant, worldly, and influential as any period in our history. Nobel odds makers frequently cite Roth, Joyce Carol Oates, and Thomas Pynchon as potential laureates, but what about John Updike, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, John Barth, J.D. Salinger, or Denis Johnson? And those are just a few of the living writers; surely the influence of Raymond Carver or William Gaddis has reached far beyond U.S. borders. To denigrate this era of American literature is not only ignorant; it’s bizarrely spiteful.

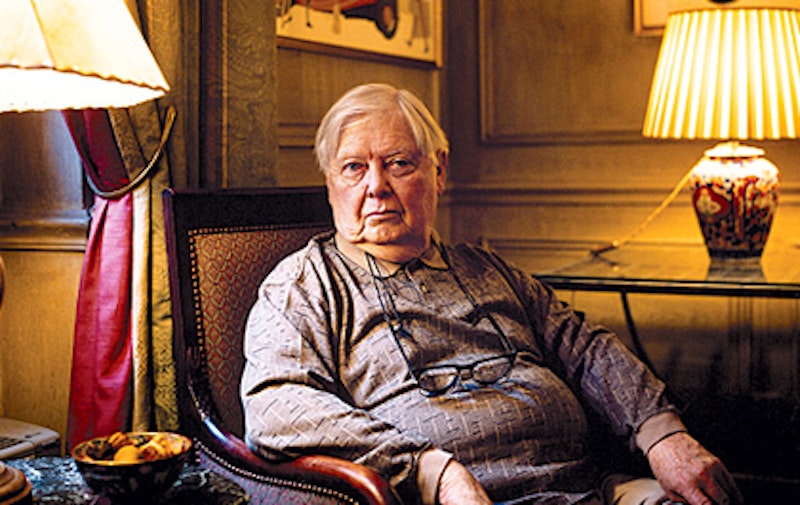

If the Nobel committee wanted to acknowledge our country, they could do worse than pick any of the above talents. But if they wanted to truly prove their knowledge of American literature’s depth, they could pick a relative unknown who nevertheless deserves the prize based on Engdahl’s nebulous “not insular/participatory in the global discussion” criteria: William H. Gass. Through novels and story collections like Omensetter’s Luck and In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, Gass established himself as one of the foremost experimentalists of the 1960s. He’s since published numerous prize-winning essay collections that encompass philosophy and literary criticism, including pieces on world authors like Rabelais, Flann O’Brien, Rainer Maria Rilke, Elias Canetti, Erasmus, Collette, Julio Cortazar, and Samuel Beckett. Additionally, Gass was a devoted and award-winning teacher of philosophy at universities throughout the country. He is a man of letters in the truest sense, and, at 84 years old, is deserving of recognition sooner than later. Otherwise, he’ll be in the noble company of the many great writers whose genius the Nobel committee was “too isolated, too insular” to recognize.