Ninety-four years ago this week a steamship called The General Slocum caught fire in the East River and ran aground off of North Brother Island. 1,331 people were aboard and in the 10 minutes the ship sailed passed the upper eastside of Manhattan, 1,021 died. Most were poor German immigrants and no movie is planned about this disaster. When poor people die in a fire no one cares. Like the 1990 Happyland disco fire of 1990.

My great-grandfather, Eugene Sullivan, was a fireman stationed in The South Bronx in 1904. He rode out to the East River in a fireboat and spent all of June 15, 1904 trying to rescue non-swimmers who’d jumped off the burning boat. The fireman tried, but they were too late. The bulk of their work consisted of pulling corpses out of the water and lining them up on the beachhead of the island. For this gruesome work he received a gold medal with a carving of the General Slocum and the simple legend, “Hero.” My sister still has the medal.

Ninety-four years is a long time. I figured with only 310 survivors it would be long odds on finding anyone that was still alive, and if there were they’d be antediluvian. I looked in a 1995 Queens’ phone book and found a residential listing for “General Slocum.” I rang it up and a woman told me she knew nothing about any ship that caught fire. My next lead led me to James Driscoll, who works at the Queens Historical Society.

Driscoll had some information, “Yeah, that number was good for an old fellow named Tom Schweitzer who passed away a few years back. He led the service every year for the Slocum in Queens at Lutheran Cemetery in Middle Village. I know the ceremony is still being held, you should try that Lutheran church in Queens.”

I asked if Driscoll knew of any survivors. “As of 1994 there were two survivors left.”

One was Mrs. Catherine Gallagher-Connelly of Manhattan, who was over 100 years old. The other was Mrs. James Witherspoon, a retired teacher who lives in a New Jersey nursing home. Four years later the odds are getting thinner and thinner of anyone being left. Driscoll told me to get in touch with Florence Buchholc of Middle Village, Queens who’d taken over the ceremony honoring the Slocum dead.

Buchholc spoke to me in a voice similar to my grandmother’s, sweet and not too impressed with herself. “Every year we’ve been having the service at Trinity Lutheran Church on Dry Harbor Rd. It’s a nice little gathering. We then we go over to the Lutheran Cemetery on Metropolitan Ave. to the stone memorial for the Slocum dead. I took over the event because well, I don’t want the tradition to die out. We’re so close to the 100-year anniversary I want to keep it going. Last year we had 25 people come out. I hope there’s more this year. I like to see the young people get involved. It’s going to be on Saturday June 13 at 11 a.m.”

Buchholc told me that she knows for sure that one survivor, Mrs. Witherspoon, is still kicking, “I don’t know if she’ll make it. She was only a baby on the boat when it went down. So I guess she’s like 95 years old.”

So what led to her interest in the Slocum? “I got involved because my mother witnessed the boat burning and always told me about it. Then we moved out to Middle Village where a lot of the victims are buried and it became a part of my life. There are three huge stones in the cemetery honoring the 61 unidentified dead of the Slocum. The middle stone had a bronze plague of the ship but it kept getting stolen so a collection was made to carve the ship into the stone.”

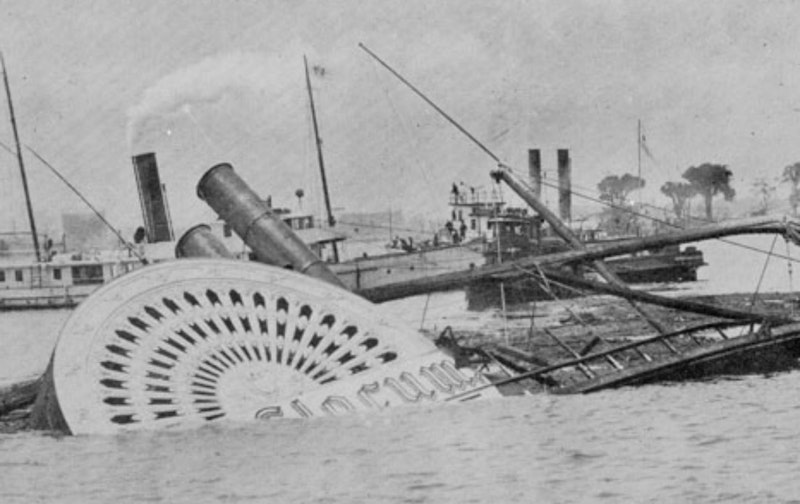

After talking with Buchholc, and begging off an invitation to travel to Queens to memorialize the dead, I researched the boat. The General Slocum was an excursion steamer built in 1891. It was 264 feet long at midship and had twin paddle wheels. It was named after Major General Henry Warner Slocum who commanded the right wing of Union Army at Gettysburg and served three terms as a Brooklyn congressman. In the 1890s it was considered a high-class vessel and for 50 cents you could travel from a New York pier to the Rockaways. But the Slocum had a couple of close calls and ran aground a few times. It became synonymous with misfortune and became a working class vessel.

St. Marks Lutheran Church on E. 6th St. chartered the Slocum for an annual excursion on June 15, 1904, a Wednesday. The church people were heading out to a picnic at Locust Grove in Suffolk County. They left the E. 3rd St. pier at 8:45 a.m. Of the 1331 people who got on board 800 were women and 500 were kids.

The boat was steered by Captain William Van Schaick. As it was passing Hell’s Gate, a little boy told a crewman about a fire on the lower deck. He ignored the kid and in six minutes the boat was in flames. Van Schaick tried for the Bronx shore at Port Morris but wound up on North Brother Island, then a home to a hospital for TB patients.

Most of the immigrant women and children were unable to swim and choose to jump into the river instead of burning. Some wore ancient life jackets called ”Kahnweiler’s Never Sink Life Preservers.” They were full of powdered cork and exploded when they hit the water, dragging the people down. The lifeboats attached to the ship’s ceilings were never put in the river. 1021 died. North Brother Island was lined with corpses. Some bodies came afloat days later in Bronx and Lower Manhattan.

On June 18 a procession of 156 bodies in glass-enclosed hearses drawn by dark horses in nettings of black went across The Willamsburg Bridge and headed to Lutheran Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens. The Slocum disaster is what made Ridgewood, Glendale, and Middle Village bastions of German culture. They moved there to be near their dead.

Only Captain Van Schaick was tried for the negligence and condition of the Slocum. He was convicted of manslaughter and was sentenced to 10 years. He served three and a half years and was pardoned by President Taft. He died at 90 in 1927. Incredibly the hull of the General Slocum was used as a barge after this disaster and was christened ‘The Maryland.” It sprung a leak loading a load of Coke and sunk in 1911 a few miles south of Atlantic City.

James Joyce set Ulysses on one day in Dublin, June 16, 1904. In his classic novel he writes about the Slocum: “Terrible affair that General Slocum explosion. Terrible, terrible! A thousand causalities. And heart rendering scenes. Men trampling down women and children. Most brutal thing… Not a single lifeboat would float and the firehoses all burst. What I can’t understand is how the inspectors ever allowed a boat like that… Graft, my dear sir. Well of course, where there’s money going there’s always someone to pick it up."