I have been a street map collector since my grade school years. Though I had friends and played in the schoolyard for sure—though I was no one’s idea of an athlete—many of my spare hours were spent poring over street maps of Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the other three boroughs (which I wouldn’t familiarize myself with until a few years down the road) as well as consulting the Little Red Books published by a map company called Georgaphia (they still sell the only widely available hand-drawn current NYC map). I’d look up where streets began and ended; their cross streets; and the house number addresses at the cross streets.

Even at that age, I’d check over the map carefully, with either a magnifying glass or eye pressed closely near the page, for dotted lines signifying demapped or ancient roadways, and look them up in the Red Book Talmud. I would buy lined paper with my allowance, the kind used in school for what they used to call “themes,” and copy down the street names in order, as well as where they began and ended, an activity that sharpened and honed my handprinting into a preeminent example of legibility, a skill that helped me label mixtapes in future decades but hasn’t made me a lot of moolah.

When I began high school, I began to spread out a bit from the five boroughs and purchased an entire set of what Hagstrom had to offer, from northern New Jersey and Philadelphia to Long Island and Westchester. I began to notice what letterer and artist did which maps by letterforms and strokes; I’m disappointed that Hagstrom draftspeople always remained anonymous, unlike comic book artists. To me, rival Geographia, while a bit more legible, was always a slight step down, Pepsi to their Coke, Hydrox to their Oreo.

I wasn’t done with Geographia, though. In the mid-20th century, they had a nationwide reach. When the company discontinued their line of maps outside the NYC area in the early '70s, I ordered one each of their entire inventory. To this day, if one needs a 1950s map of Akron, Ohio in reasonably good shape, I can be reached at kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com. In the 1980s, I discovered the Thomas Brothers line of Los Angeles-era maps. I became something of a connoisseur. Then came the 2000s, and computer-generated paper maps that were bland and boring. The city maps available on CD in the 1990s and 2000s were horribly crude, but Google has stepped up its game in recent years and has turned in gorgeous, super-detailed city maps, and, with the Street View trucks, provided scenes of cities that I could only guess what they looked like from maps.

A “new” old map of Manhattan is always a pleasure for me. I scan it carefully for things not shown on other maps, or archaisms left over from previous NYC eras. Just this week, I found a few things on a 1903 Manhattan map by the J.N. Matthews Company, one of a number of companies that produced NYC maps before Hammond and later Rand McNally and Hagstrom largely took over the market. The company was founded by Buffalonian George E. Matthews, who named his publishing company after his father. The main business was the newspaper, The Buffalo-Courier Express, which J.N. Matthews purchased in 1878, and with a new four-color “prism print process” J.N. Matthews also expanded into publishing of other kinds, including this map.

I was intrigued by the “Cemetery” shown between 1st Avenue, Avenue A, East 11th, and 12th Streets. Though there are an existing pair of ancient cemeteries in this neck of the woods, the New York Marble Cemetery and New York City Marble Cemetery on East 2nd Street on either side of 2nd Avenue, the “Cemetery” site today is dominated by stores and apartment buildings on A and 1st, with a pair of middle schools and a playground on East 11th and 12th in between.

The website New York Cemetery Project had the answer. In 1833, the old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mott Street, still standing, founded a cemetery on this block for parish interments, and laid over 40,000 parishioners to rest here. In 1848, St. Patrick’s opened a much larger cemetery in southwest Queens, Calvary Cemetery, and the old cemetery in Manhattan lay unused and eventually, vandalized by young rapscallions and bootblacks. It wasn’t until 1909 that St. Patrick’s relocated the interred to plots in Calvary Cemetery, and the old grounds were built on over the decades.

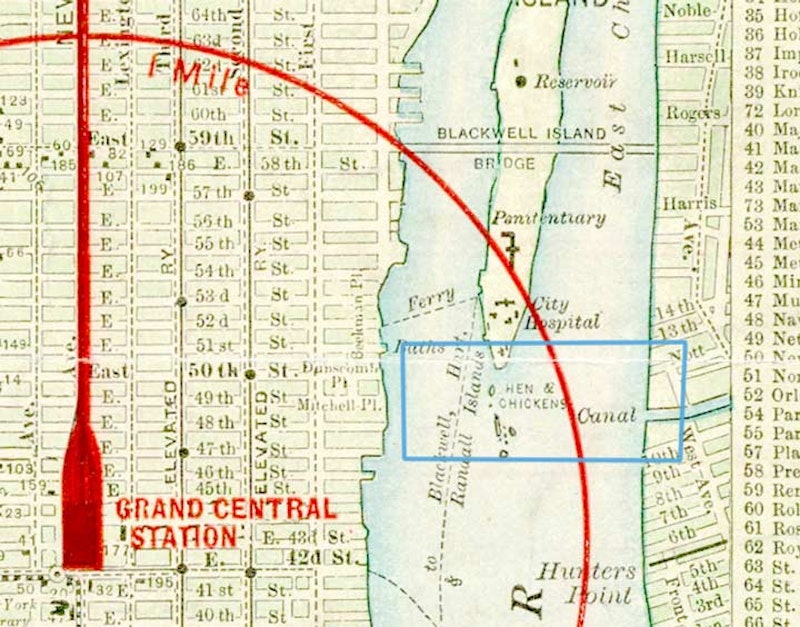

It wasn’t until 1899 that Broadway was Broadway all the way from Bowling Green to the Harlem River (and north of that, into Westchester County). It follows a Native American trail that was straightened somewhat into Bloomingdale Road south of Columbus Circle and followed an old road called Kingsbridge Road (so named because it crossed a colonial-era toll bridge by the same name over the Harlem) into the Upper West Side and Washington Heights. This map from 1903 still insists on the Boulevard Lafayette name Broadway carried above Columbus Circle (though it shows the IRT subway, which wouldn’t open until the following year). As we learn from Gil Tauber, the entire stretch of Broadway from 59th to 188th straightened Kingsbridge Road into The Boulevard in 1868, while the great French general’s name was appended in 1894 for only 5 years—when the whole stretch became Broadway.

The East River was quite treacherous for navigators from pre-colonial times until its large collection of rocky stretches at the Hell Gate was exploded by the Army Corps of Engineers, who produced the largest man-made explosion in American history in 1885, shattering the minuscule islands in the strait. The bits were later used to construct Mill Rock in 1890, which is today a nature preserve.

The East River still has a number of small islands south of Roosevelt Island that become visible at low tide, such as Hen and Chickens. The Matthews map is the only one I’ve seen that happens to list them. I came up on Hen, at least, while visiting the FDR Four Freedoms monument. Beyond Hen to the south is U Thant Island, a man-made island formed from excavations for what became the #7 train tunnel. Other colorful East River island names were the Gridiron, Hogs Back, Holmes Rock, and Frying Pan; the Army Corps ended their existence in 1885. But the Hen still pecks, as may the Chickens.