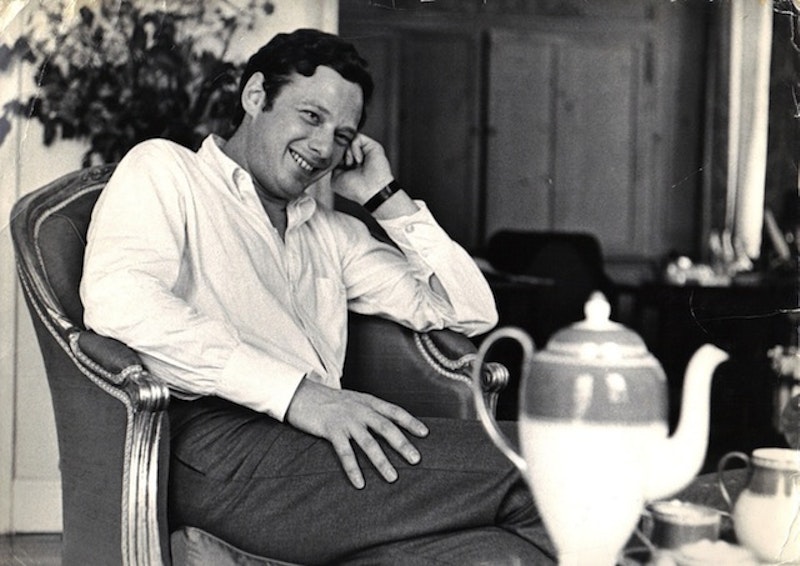

Brian Epstein looks like a cream cheese mouse that’s been topped with brown hair and is very good at passing for an English gentleman. He’s suburban. But he’s high-level suburban, and a schmo like me can admire him. That fluting sound and the assured flick of the little finger—the head waiter comes hurtling over. This is pre-fame. The group’s doing radio shows for greater Yorkshire, that kind of thing. But Brian gets special attention.

He wants me to know it’s been like that for a while. When we enter, he declines the table the maître d’ offers and points at another: by the window, suitable for three or four. The party is Brian and me, no one else, but the maître d’ accedes. At the moment the fellow does so (“Certainly, Mr. Epstein, if that is agreeable”), Brian flushes. Hints of cherry bloom near his eyes and nostrils. His chin tucks, his nose seems to project; a pinched curl of fat squeezes into view, right along his jaw. He looks like a membrane hard pressed by its contents.

He wants to see what I think about this. His eyes move sideways, one big step, the two of them together, and then one step back where they started, like he hadn’t been looking. We proceed to our table. Those two moments, a pair of beads, will be in my mind whenever I talk to Brian or hear his name.

What did he see when he cut his eyes over? Me grinning like Bobby Werndale, the top tennis star at my high school. He’d grin like the coach had just decided that sunshine was shiny and nice. Now I grinned this grin for Brian. I think it reassured him.

Seating us, the waiter is affable. I suppose Brian must tip very well. He and Brian exchange smiles. The waiter has whisked Brian’s chair into place for Brian to sit, and Brian nodded at the clean line that the chair traveled. Thus the smiles: Brian had recognized good work, the right touch, and the waiter paid tribute to Brian’s acuteness. All this would have gone on with or without me, or that’s my guess.

But here’s what I add. I’m a boy of college age wearing a dark suit, and my hair’s like Buster Brown or Prince Hamlet hair. It’s a bank of hair, floppy but straight, glossy, and it’s hanging down. The waiter can’t find my eyes. He’s seating me, and apparently eye contact is important for this process. But he has to hunt for my eyes. He’s quizzical about this.

“Begging your pardon, sir, but I’ve seen that hair only on my grand-nephew Bobby and his chums. In the council school.” That’s like fourth or fifth grade in the U.S. “Among the older boys, is this getting to be the style?”

I answer as a Beatle. I’m grinning and loud, and take a swoop in my behavior and logic, but I’m on the man’s side. Beatles are like that. Most of the world doesn’t know it yet, but they will, and here I play out the combination. I’m the lively spirit of tumult that overturns order because the two of us—you and I, me the spirit and you the civilian—both know about taking a joke. “Just a few of us,” I say, or sing out. “We said, ‘If Bobby’s doing it, okay.’” I say this with a full-bore American accent, a blare that’s guileless and jaunty, that’s proud of itself and ready to be pals.

The waiter’s long, weathered olive of a face folds at the middle. His wiry shoulders, in his jacket, take a surprise dip in the direction of his hips. He’s laughing. When he straightens up, he’s still laughing. “Very good, sir,” he says. “Very nice.”

Brian looks at me with the face of one who sees the world turning out as it should. I see that look on his face when the other boys are there. Now I get it too. I think I really am a Beatle.

“There is one thing,” Brian says. “One thing I hope.”

“And what is that?”

“I hope you shall call me Brian.”

“Brian,” I say, “I certainly shall. I see no problem there.” We clasp hands. I am now his client, his prize.

But I refer to him as Epstein. When he’s not around, that’s what I call him. The other boys don’t. With them it’s always “Brian.”

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3