I shouldn’t have trusted Elif Batuman, but I did. I like The Possessed. I like it more than most playful belles-lettres books about odd topics and weighty cultural items (in this case, a summer in Uzbekistan and the study of Russian lit, kind of). I like the author too, at least as she comes across in her book. Batuman went to Harvard and then got a doctorate from Stanford, and she published her first article in The New Yorker. That kind of thing dazzles and intimidates me. But she presents herself as being a bit of a goof, so she’s a dazzler who’s ingratiating. Reading the book, I came to think of her as a buddy. I wish I hadn’t, because after The Possessed I decided to read a London Review of Books essay she had written, and that essay has broken my confidence. I’m now in the middle of a depression.

The essay has to do with short story writing. Batuman read two years’ worth of literary short fiction as collected in a Best Of series. By the time she was done, she had figured it was all pretty much a crock. Which pleased me, since when I was in college I wanted to write and I knew that short stories were how you started. When the TA for my first writing class told me I had a future, I bought the latest anthology of O. Henry winners and was then stumped to find I couldn’t read most of the stories. Maybe it was their fault, I’ll never know. The truth is that I had stopped enjoying literature when I was 15, the same age that I decided I would be a writer and impress all the adults. By the time I took my undergrad writing class, I pined to be accepted as an author of the sort of thing I couldn’t read. Let me underline that word: pined. My life was hollow because I wasn’t a writer after all.

I wadded together a substitute life, one that was eventually touched by a brief ray of pleasure when The Possessed informed me that the elect, the people who made the cut, were a bunch of trivial woodworkers in prose, drones who allowed their sanctimonious mottoes (“Kill your darlings,” “Omit needless words”) to turn literature into a midget exercise like whittling or newspaper puzzles:

I thought it was the dictate of craft that had pared many of the Best American stories to a nearly unreadable core of brisk verbs and vivid nouns—like entries in a contest to identify as many concrete entities as possible, in the fewest possible words. The first sentences were crammed with so many specificities, exceptions, subverted expectations, and minor collisions that one half expected to learn they were acrostics, or had been written without using the letter e. They all began in media res. Often, they answered the ‘five Ws and one H.’

A Stanford doctoral candidate in comparative literature delivered this judgment. She wrote better than the writers, and she was more elect than the elect. But then I read the article from which the words above had been mined. And I realized something. Those busy opening sentences are a bit much, but they’re still the same sort of thing I try to write when I try to write fiction. I realized this because Batuman’s article singles out the following as an example of egregious tendencies:

In later years, holding forth to an interviewer or to an audience of aging fans at a comic book convention, Sam Clay liked to declare, apropos of his and Joe Kavalier’s greatest creation, that back when he was a boy, sealed and hog-tied inside the airtight vessel known as Brooklyn New York, he had been haunted by dreams of Harry Houdini.

I think that’s a good sentence. There’s a lot going on, but you don’t get overload. Reading that sentence, I’d like to read on. In fact I did read on, since The Adventures of Kavalier and Klay is one of the few pieces of quality lit that I’ve managed to enjoy. Now I find out it’s no good.

As it happens, I’m writing a novel. I was already middle-aged when I started it and work has been going on for a decade-plus. During that time I haven’t been doing much else, not unless you count reading political blogs. So you could say I’ve got a lot riding on my book. The novel has a grabber first sentence of its own, not as action packed as the Chabon but still in media res and equipped with a character name. Note that I didn’t imitate Chabon—God help me, I wrote the sentence so long ago that Kavalier and Klay had yet to be published. My first sentence is a cousin to his just because it’s typical. If my novel is ever finished, the manuscript will land on some agent’s desk, part of a fat pile of would-be books with their buzzy little openers.

My dive-right-in first sentence wasn’t even the result of reading other such sentences. Instead I had the wisdom handed on to me. A girl I worked with told me how her friends, when they tried writing stories, always committed the blunder of beginning in long shot. “‘A man was standing on the street near a house,’” she said, with a marked tee-hee element to her voice. Another girl, also a colleague, said her fellow writing students always turned out first sentences lacking in “authority.” As an example of how to do it right, she cited the opening to a Flannery O’Connor story, a sentence with a character’s name, a reference to the character’s aunt, and a brief description of their typical routine and of how they broke their routine on the particular day the story opened. The sentence may also have given the day of the week. All that sounded good to me. When I decided to write my novel, I went with the same approach.

I thought I was being special, since being a good writer is a special sort of thing. Instead I was being ordinary. Of course, if I read more I might not have been stuck with whatever scraps of wisdom had washed up on my personal shore. Kind of foolish, when you think about it, basing your life’s work on driftwood. But my whole approach to writing has been neurotic. If you don’t like reading literature, why decide to write it? From a mistaken idea of prestige, in my case. My life is a mistake, and I know it because my first sentence is a mistake. Up there in Stanford, Elif Batuman could tell.

My Life is a Mistake

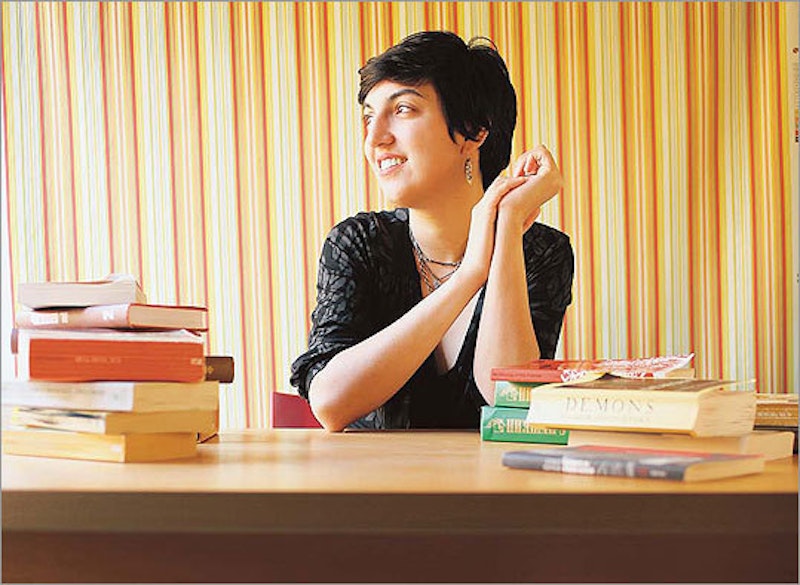

A self-doubting man reads Elif Batuman's The Possessed.