The first asshole I knew was my dad. From the time I was five years old, I watched him beat my brother with a closed fist, punch holes in the wall, throw my mom to the ground and call her a bitch, go on coke benders, and leave porn mags stacked in the garage without caring who saw them. Penthouse Letters was the first reading I did on my own, at seven. My dad left us, sent no money for support, never wrote, rarely called, and cancelled about 75 percent of the visiting days he’d scheduled.

In college, I was trying to be a writer before I knew how to be a man. My heroes were cold-hearted examples, like my dad, writers of the West whose male protagonists barely spoke to their sons, or writers of the Midwest who protagonists all mimicked Raymond Carver’s characters and barely spoke to anybody. My favorite writer back then was Jim Harrison, whose death this year prompted many online tributes. Harrison transcended heroism and was like a father to me—and boy were his characters pricks like Dad: they screwed anything that moved, drank and ate like pigs while claiming to be conservationists, blew through wads of cash while insisting they were blue collar at heart, and committed outlandish breaches of morality against their spouses. Everything was justified in the name of Art.

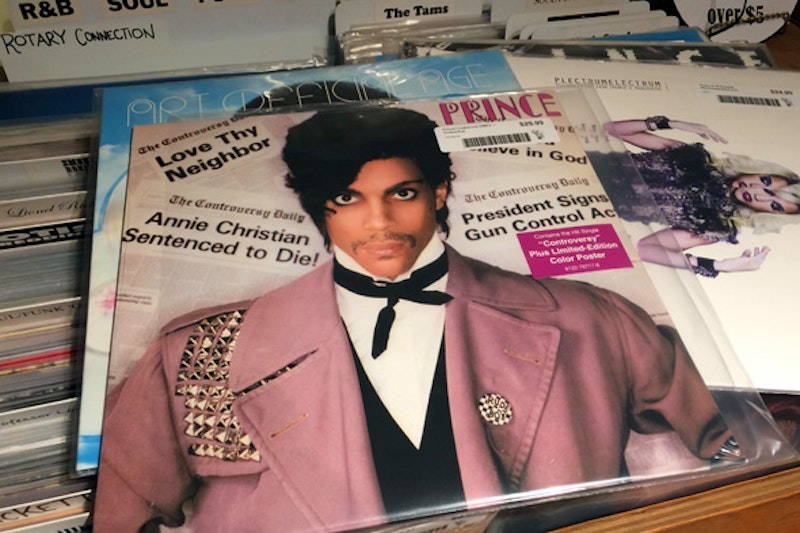

In my 30s, I found myself alone in bars, with two young kids at home and their mom a woman I could barely speak with anymore. My marriage was failing, and half of that failure was mine, as I’d allowed myself to become a character scribed by heroes who should’ve long ago vacated their seats. There was a jukebox in a bar called Mulligans, and I’d put in dollars and play “Purple Rain” over and over again while I wrestled with my crumbling family. I knew that Prince, if I listened long and hard enough, would bring me back into the fold, a cradle akin to religion or love, or to the arms of my mom before they were torn from me by rougher hands.

Prince, after all, had seen me through the moments of youth that had otherwise been sheared by hurt. His records had played non-stop in my bedroom, walking and then running me through fears, allowing me to be a freak and sexy and mindful all at once, to be weird but to expect love, to be whomever the fuck I wanted to be so long as I was nice to people and held a vision of the future that would always be greater than the reality of the present.

When I stepped through fistfights, broken hearts, or my failing marriage, Prince was there. Now that I’m becoming old, his passing is a marker. When I step forward to hear him again, I hope that what I’ve brought along, in the entire body of my work, will equal the greatness of at least one song. I have no other gifts to give him in return for his love. I have no way to thank him but to become better than what I’ve been.

Prince is the father gone from me again, but he’s the father who left me with a mandate to follow brilliance. In the afterlife, I’ll tell him what I couldn’t now, that he was there for me, and he held me, and he brought me to a foreground. In this life, I was never on my own: it took Prince dying for me to realize that.