I didn’t think I would be alive to write this. As December 21, 2012, got closer and closer, a part of me really believed that the Mayans were onto something with their expiration date for the world. Maybe, like modern believers of the apocalypse, the Mayans pondered fiery pits of Hell or the left behind wandering among empty sets of clothing, but they gave no visions of what would happen on 12/21/12, just that the 22nd would never come. But it did come, and here I am on Christmas night, half listening to a radio special on Santa and eating hummus that I think might have gone bad. This is my 30th Christmas, an age I never thought I’d live to see.

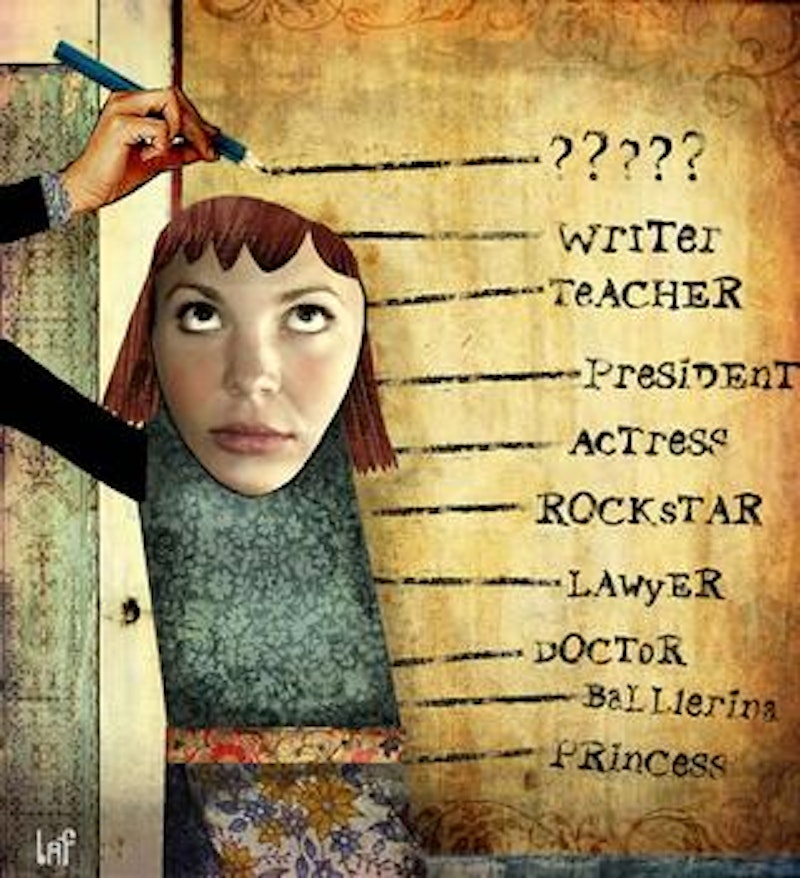

When asked as a child what I wanted to be when I grew up, I gave the usual answers—a doctor, a lawyer, an artist on the streets of Montreal who drew tourists with giant buck teeth and tiny bodies—but really I had no plans to have a career because I had no plans to grow up. Many people think they will never live to the age of 30 or 50 or 80, maybe because it’s too hard to imagine ourselves with crow’s feet and gray hair, yet when I used to hear other people say this, I would think, That’s ridiculous. The average life expectancy in this country is 78 years old. Of course you grew up. Me, on the other hand, now that is a surprise. It’s not that I thought I would die young, just that I would never get old, a natural extension of believing, as I did, that I would never die. Everyone else would, of course, but I, Katie Herzog, nearly born in the parking lot of Pedro’s Porch Mexican Restaurant in Asheville, North Carolina, with a low weight of eight pounds, 12 ounces, would not die.

Articulating thoughts like this are the reason the therapist I saw for a few years was always trying to get me to see that I was not, contrary to my own belief, special; that I would die just like every other human. It was less those 50 minutes a week on a shrink’s couch that made me finally admit that I’m no more exceptional than anyone else you’ve never heard of. I hit 25, and that was unbelievable, and then, even more remarkably, I hit 29. Now 25 seems young, almost infantile. Still, though it’s only days until the calendar flips to the year of my 30th birthday, I’m often surprised that I am not just old enough to be a lawyer or a doctor or a Canadian street artist, I’m on the verge of being too old to start doing those things. I’m equally as surprised when I hear of my friends and peers having children now, at the tender age of 30. When told the good news of a friend’s pregnancy, I smile and think, babies having babes. How could the people I went to kindergarten with be parents when I’m scarcely closer to knowing what I want to be when I grew up than I did when we were five? For this reason, I half wanted the Mayans to be right—if the world ended, I’d stop worrying about getting older.

It wasn’t just aging that I used to think I was immune from. It was everything. I could smoke a pack a day and not get addicted. I could drink every night and never get the shakes. I could be late for work, show up stoned or not show up at all, and I’d never get fired. And the person I ended up with would be no less than perfect. I would never settle for anyone less than my soul mate, a concept I don’t actually believe in but was sure applied to me anyway. For the most part, time proved me wrong: I have the lung capacity of a 9/11 cleanup worker; I had the shakes for weeks on end and finally had to quit drinking; and I got fired so many times that my resume isn’t worth the cost of a sheet of paper. But, surprisingly, I think I’ve found my person, and she really is perfect.

In my early and mid-20s I dated some and had plenty of mediocre sex with people I wished were gone when I woke up the next morning, but I never saw myself actually marrying anyone. The older we get the more some people worry about never finding a partner, but I never did because I’d rather be an old maid than with someone who was less than perfect. If I couldn’t find someone who was smart and funny and beautiful and interested in the world, I would be alone, and contentedly so. This had begun to seem more like a possibility in recent years. After my 29th birthday and still never having really loved someone enough to wed them, I started reading pop psychology articles about how being single can be a whole identity, like maybe some of us really are meant to be single for life, and I tried to embrace this.

It’s not that I couldn’t find someone, it’s that I chose not to, I told myself. But then, a few months before the world was supposed to end, I met Lorillin, who is better than perfect because she is only perfect for me. Actually, there are both men and women who would disagree, who would argue that she is perfect for them as well, but this time I’m sure that I’m right. We are not the best people—we laugh at Holocaust jokes and see the value in getting big dogs because they have shorter life spans—but we are the best for each other. She is funny and smart and beautiful and interested in the world and when I’m with her, I stop thinking and worrying and just am. After I met Lorillin, I started to imagine a life with another person—settling down, getting married, doing the things people do when they get older—and it sounded good.

Meeting Lorillin wasn’t the only thing that happened in 2012. I also traveled around the country, staying alone in hotels and changing all the pre-set radio stations to NPR in rental cars. There was a lot I didn’t get done: I didn’t finish, or start, that book I hoped to have written by now, and I didn’t master the forearm stand or learn how to bake bread without the density of wet newspaper, but I did run a mile once last spring and I finally started paying my own car insurance. But mostly when I look back on the past 12 months, it’s only fall and winter that are truly memorable, because that’s when Lorillin entered my life, and it changed everything.

I’m now preparing to do something that I would consider crazy if anyone else did it: I’m going to move 3000 miles across the country to be with this girl. If an acquaintance told me she was going to do this, I would state my congratulations while thinking, She has lost her damn mind. If a friend told me the same, I would try to talk her out of it and if my sister said this was her plan, I might even call our mother. And yet, here I am on this holy night, looking for jobs in a new city and hoping that my next Christmas will be with Lorillin. This could be the biggest mistake of my life, giving up my house and my job and my life to move to a city and a girl I barely know, but I’m ready to grow up, and I want to do it with her. We’re all going to die, after all. Might as well start living.