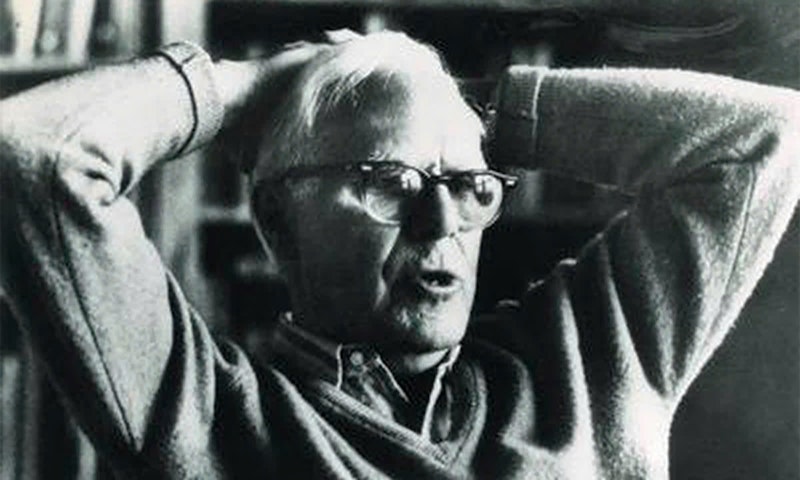

Martin Gardner (1914–2010) was a science writer known for debunking paranormal and supernatural claims, but when asked if he was the most skeptical man alive, said, “I doubt it.” He believed in God and an afterlife but adhered to no religion. In The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener, he wrote: “Although there may be rewards and punishments in the afterlife, who are we to know what forms they will take? And there are many other questions involving space and time in the life to come that it is wise not to try to answer.”

Gardner added: “William James, in his little book Human Immortality, said that as far as he was concerned every leaf on every tree could be immortal. Maybe, but the remark leaves me more bemused than cheering. How about strands of hair snipped off by a barber, or clipped fingernails?”

I thought back to Gardner’s writings on immortality as I read about an emerging physics hypothesis, called quantum memory matrix, propounded by Florian Neukart of the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, who writes: “In this approach, spacetime is not perfectly smooth, as relativity suggests, but composed of discrete elements, each with a finite capacity to record quantum information from passing particles and fields. These elements are not bits in the digital sense, but physical carriers of quantum information, capable of retaining memory of past interactions.”

Neukart: “Each interaction writes something permanent into the structure of the universe, whether at the scale of atoms colliding or galaxies forming.” The universe, in a sense, “remembers” everything that’s happened in it, which may offer insights into physical phenomena. An extra gravitational effect on stars and galaxies, long attributed to unknown “dark matter,” could have a different cause: “Regions that have accumulated more informational imprints respond more strongly to motion and curvature, effectively boosting their gravity. Stars orbit faster not because more mass is present, but because the spacetime they move through carries a heavier informational memory of past interactions.”

Future studies of black holes, using technology more sensitive than currently available, could offer a test of this hypothesis. Hawking radiation, emissions from black holes theorized by the late cosmologist Stephen Hawking, would carry subtle traces of the history of the high-gravity objects, if the informational view is correct. Lab experiments with quantum computers may also assess the quantum memory matrix proposition.

Yet Gardner, writing in the 1980s well before this concept developed, argued that no cosmic pattern could substitute for personal immortality: “What difference can it make to you and me if the mass-energies of our body’s particles will be conserved, or if the atoms of our brain will continue to vibrate somewhere in the cosmos? In that sense of immortality, every blade of grass, every pebble, every snowflake is immortal. To say it in plainer language, nothing is immortal except perhaps mass-energy, and for all we know, it too may eventually vanish into a black hole if the universe stops expanding and goes the other way.”

What would personal immortality be like? Gardner contemplated various theological debates about the afterlife, noting for example that Muslims and Christians have broadly differed on whether there’ll be sex there (the former saying yes, the latter no). Gardner regarded such speculations as “frivolous guesses about details God has wisely concealed,” but also noted that “we cannot leave the nature of the afterlife a total blank,” if we want to construe it as something desirable.

Hence, he sketched out some hoped-for conditions: “We do not want to live again in some vacuous disembodied state. We want to live again in a manner that somehow resembles life on earth.” Also: “We cannot, at least I cannot, imagine how I can ‘live’ unless I am in some sort of time and space, retaining my consciousness of self, which means retaining my memories.” Without weighing in on sex, he noted: “Nor can I conceive of living again unless there are others there whom I have liked and loved, and others yet to like and love.”

Any afterlife worth living in, Gardner argued plausibly, would require “things to do, challenges to be met, struggles and adventures to undergo.” He acknowledged, though, that all this is a matter of faith and hope, adding: “We know nothing—nothing whatever—about heaven. At the same time let us not be ashamed, when we dream our crazy dreams of hope, to model heaven in the only way we can: as life that deserves to be called life, not something it would be more honest to call death.”