Many years ago, an editor at The Chicago Quarterly Review sent me one of the most colorful rejections I’ve gotten from a magazine: “I can’t think of a single person who’d want to spend thirty seconds with these morons,” meaning the characters in my short story but also, in a way, me.

It was a story about falling in love with a stripper in Missoula, titled “The Machinery Above Us,” and Eclipse Magazine took it some time after that. There were graphic parts in it and I noticed that the rejections came most fluidly from the Ivy and Ivy-adjacent literary journals on my submission A-list. The Partisan Review, The Paris Review, Doubletake, Story, and Boulevard rejected it with a quickness. They seemed to find the material distasteful.

It would’ve been useless to point out the long tradition in the West, especially in post-1940 American realism, of writing about sex workers, strip joints, addicts, dive bars, diners, and cheap hotels. That was the subject matter of my 20s, the emotional terrain I knew, and much of what I read. I was uninterested in writing complex social satire about managers of art galleries, dinner parties in Manhattan, and socialites discovering bisexuality, which were dominant themes in publishing at the time.

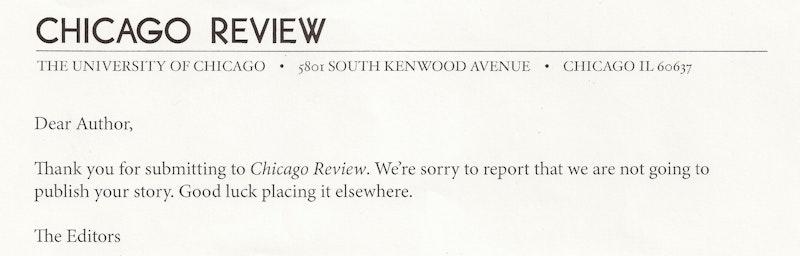

The TCQR editor had scrawled his response on a “rejection slip,” which, for most magazines and journals, amounted to a small piece of paper with the logo and a standard boilerplate rejection. Most of them went something like “Dear Writer: unfortunately, there is no place in Lost Nose Monthly for your story. Thank you for submitting. — The Editors.”

Traditionally, if an editor summoned the herculean effort necessary to write anything by hand on one of these slips, he or she was implicitly encouraging the writer to send something else. In the rapey, atavistic world of small magazine publishing, no often meant yes. But those were different times, before sterile cut-and-paste email rejections replaced the little colorful soon-to-be bookmarks.

I had two shoeboxes of them by 2000, when most publications started transitioning to a digital slushpile. In one of my graduate student apartments, I created an enormous collage of rejection slips over my writing desk—because they didn’t depress or discourage me at all. I didn’t see them as a monolithic testament to my inability as a writer. Mostly, I liked the logos. A lot of them had handwritten messages, some nicer than others. And whenever I questioned what I’d been doing with my life, I could read them and nod. Yes, I’d taken a beating just like every other serious writer.

In our present all-online-all-the-time world of digital platforms, print on demand, coercive reading fees, and auto-responses, “no” nearly always means “no,” even if you do get a personal response from an editor. Often it means, “Never submit to us again and don’t let the door hit you on the way out.” And these days, it can sometimes mean, “I looked you up on Twitter and am rejecting your writing because physically assaulting you is not feasible at this time.” It rarely means, “We all love you over here and want to send you a cupcake.”

Small magazine publishing has never been so weaselly, so desperate, so unprofessional, and so caught up in reactionary politics. The humor and directness that used to be a welcome part of the submission process is in short supply. And some magazines now ask for a picture along with the manuscript instead of after acceptance, suggesting that the identity of the writer is just as critical to acceptance as the writing.

I miss the ugly poetry of paper rejection slips, especially the colorful (if sometimes blunt) rejections I sometimes got. I say “colorful” instead of “harsh” because, after writing professionally for a few years, I developed a certain toughness. When a Thai boxer kills the nerves in his shins from kicking a heavy bag full of rocks every day, what does he do? He keeps kicking. So I kept kicking. And it mostly worked. I’ve published a lot of stories and essays in a wide variety of digital and print magazines, two books, and a third coming out soon.

But I’m not boasting about small victories. Like most writers, I learned to accept occasional abuse as part of the life. “Learn to love the hate,” the crime writer, James Crumley, said to me once, along with, “If you’re not pissing at least some people off, you’re not doing your job.” Come to think of it, that’s probably true for everything. The students everyone loved in my MFA program were those who never finished their books, never submitted stories, and generally stayed drunk.

Another story, “The Problem of Evil in Hauberk, MO,” got taken by The Georgia Review that same year. Earlier, an editor at The Harvard Review had rejected it with one sentence in a formal full-block business letter format with Harvard letterhead. It read, “Your story about men behaving poorly made a few of us laugh, but we’re going to take a pass on this one.” No cupcake for Michael.

I thought about the story. Was it really about men behaving badly? It was about a high school teacher being sexually harassed by his landlady while he wrestles with the attraction he feels to one of his students. I wondered if the Harvard editors read the whole story or if they just looked at the first page and decided it was icky. A lot of my stories are icky, but I always hope the mathematics undergraduate employed by the magazine as a first reader gives me at least two pages.

Years later, I was delivering a lecture at a university book festival about small magazine publishing. An unfortunate, possibly cross-eyed editor of a local Christian publication raised his hand in the Q/A segment. He’d brought Gravity, my first collection, with him and quoted aloud from “The Problem of Evil.” Then he asked me if I was a pedophile. I said no, that it was a story, by definition something I’d made up for artistic effect and submitted to magazines for publication, which was what I’d been talking about for the last hour. You know, fiction. Then I realized he probably hadn’t read the whole thing, just the saucy bits.

Some editors are brilliant. Some will pay you. Some, like a friend of mine who was an ad exec before going into publishing, care so much that they’ll go to a writer’s house and confiscate her weed until a project gets done. Others barely know what room they’re in, like someone at BOMB who wrote back, “Hemingway has been dead for years and so has his writing” as a way of rejecting one of my stories so unlike a Hemingway story that I thought maybe they’d mixed up the manuscripts.

I’ve had work accepted only to discover that the magazine folded between the time of acceptance and slated publication. I’ve been explicitly and implicitly rejected on the basis of my skin color, gender, and ostensible sexuality. I’ve received payments for half as much and three times as much as I was told I’d be paid, praised by random magazines for writing I never wrote, and was even told by a magazine I never submitted to that they didn’t care for my work. If it sounds like I’m hallucinating, I’m not.

I got my another rejection this morning for a military sci-fi story, titled, “The Shape of Things To Come.” I don’t often write sci-fi, but I enjoy it and I think this one will eventually find a home. I’ve got that feeling I always get when a story’s about to be taken. The rejection was from Analog, a dedicated sci-fi magazine, one of the few good ones. It was polite and professional. But, as I sit here thinking about it, I might write back and ask, “Didn’t you hate it, though, just a little bit?”