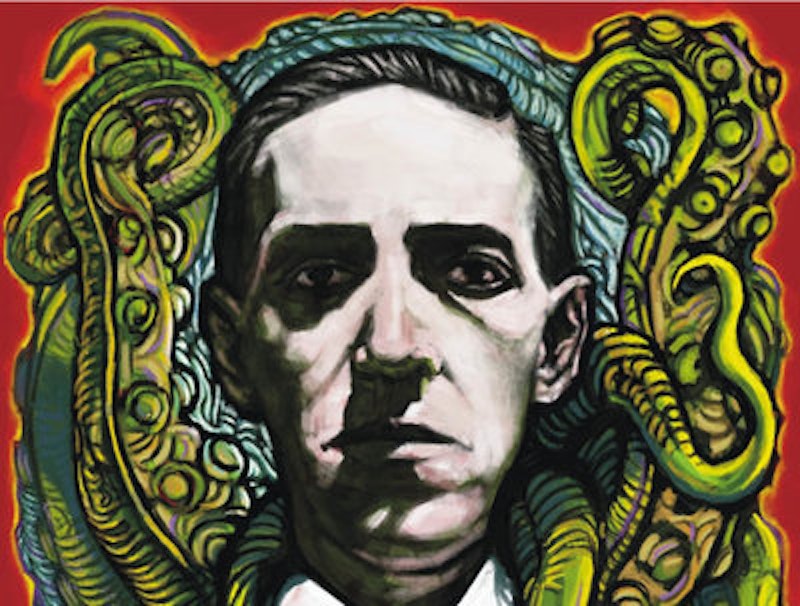

While supernatural, terrifying, and “weird” elements abound throughout the history of literature, the 20th Century witnessed a great flowering of horror as a genre unto itself. Over this period and to the present the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft, New England recluse and misanthrope, stands as model and inspiration, according to the judgment of most critics and authors. Before his death in 1937, Lovecraft was living in poverty, producing virtually nothing; just 400 copies of his first and only book of his fiction published during his lifetime were printed, half of which were destroyed.

On the face of it, Lovecraft’s posthumous success is hard to explain. While the inferiority of his prose has often been overstated, there’s no denying that his descriptions are ponderous at the best of times, his work generally lacks any developed sense of character, and many of his stories come off as sketchy and incomplete. More damning in the eyes of many, his work frequently betrays the author’s deep-seated racism, xenophobia, and misogyny. Despite these and other shortcomings, Lovecraft continues to exert a uniquely powerful influence over many who read him.

Why?

Since his death, Lovecraft’s literary and cultural stature has grown for many reasons. His disciple August Derleth started Arkham House to ensure the work would survive the neglect of the publishing houses who’s rejected his efforts to see it collected and republished. Popular authors such as Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, and Neil Gaiman avowedly carry his torch into the literary mainstream today. Perhaps most ironically, cutesy Cthulhu memes guarantee his influence upon millions who’ve never heard Lovecraft’s name. Impressive as this may be, it doesn’t explain why Lovecraft’s fiction can fill us with such profound dread a century after the publication of his first major works. More to the point, what is it about Lovecraft’s stories, despite their faults and attempts to mimic and surpass them, that inspires such dread in the first place?

Lovecraft’s protagonists tend to be academics or aesthetes, generally so implausibly naïve that we struggle to sympathize with them or understand their decisions. Though he wrote for a pulp audience, his stories are remarkably short on violence and gore, or, for that matter, action. In most of his tales there’s very little immediate, acute danger.

Instead, Lovecraft often succeeds in intimating and gradually revealing a perspective from which not simply individual human action, the welfare of a community, or even the safety of all the world’s people, but the entire scope of human life and striving become insignificant, even contemptible. As fantasist Frizt Leiber remarked, Lovecraft moved horror from the “realm of Earth to the stars.”

In much of Lovecraft’s fiction, global catastrophe is averted by desperate effort or sheer luck. At times we’re left without a clear sense of what lies beyond the story itself. At no point, however, does the reader reach the conclusion that human resourcefulness or the benign hand of Providence will ultimately save us. For Lovecraft, the best we can hope for is a mere aversion of immediate annihilation.

He bluntly laid out his pessimistic view of humanity in an essay from 1920. “We are all negligible, microscopic insects of a moment; waifs astray in infinity, born yesterday and doomed to perish tomorrow for all time. We have no reason to ask the trite questions of ‘whence, whither, and why,’ for it is our finite, subjective, rudimentary intellects which conjure up the notion of purpose. According to all the evidence we can command, we came from chaos and will return to chaos; drifting in a blind mechanical cycle devoid of anything like a goal or object.”

Lovecraft’s attitude bears closer similarity to the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer than to the muscular cynicism of his friend and fellow pulp heavyweight Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan. We’re not only at the mercy of an indifferent universe, but the victims of our own curiosity. Understanding will not save us, it can only reveal a horrifying reality we can neither escape nor ameliorate. His is a universe beyond our capacity to understand or control. The cosmic scope of both our ignorance and impotence hides from us the objective reality of our hopeless situation: “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age” (“The Call of Cthulhu”).

Like Schopenhauer’s Will, the fabric of Lovecraft’s universe is seldom intelligently malignant. Human categories such as good and evil don’t figure in the phenomena revealed by our blind delving. When the universe is conscious of and concerned with our existence at all (as in “The Shadow Out of Time”), we appear as minor curiosities toiling under the illusion of our own significance. The obliteration of this illusion, in the reader as much as in the characters of Lovecraft’s fiction, constitutes the final and defining effect of his best work.

Lovecraft’s relentless and universal misanthropy lend his fiction an oppressive weight of dread. The optimistic values of the Enlightenment are inverted and warped to appear both naively uncritical and perilous in their efforts to bring the world within the scope of human knowledge. It’s an epistemological horror, from which, once glimpsed, there can be no escape.

This nihilism, undermining as it does any faith in society, culture, or intellect, account for the enduring impact of Lovecraft’s fiction, fraught as it is with the author’s and his era’s limitations. No moral, aesthetic, or intellectual relief reconciles us to the universe Lovecraft reveals.