When I first heard the subject of John Higgs’ new book I was baffled. He said it was based upon his observation that the first Bond film, and the first Beatles single, came out on the same day: Friday, October 5th 1962.

I couldn’t see the connection. Dr. No is a big-budget Hollywood movie which would’ve taken months, and lots of money, to make. “Love Me Do” is a low-budget, below par Beatles song that made little impact at the time. It reached number 17 in Top 20. Not bad for an unknown group from Liverpool, but hardly a musical revelation. It’s lyrically uninteresting, showing none of the originality revealed by their next record, “Please Please Me.” Dr. No, on the other hand, is glamorous, glossy, sexy, and full of adventure. Fast-paced, with set piece special effects and risqué sexual encounters, it was an immediate hit and the start of a franchise that has continued to this day.

In comparison “Love Me Do” is pedestrian.

What point is he trying to make, I thought? It’s like comparing things in different categories, like recipe books and car manuals, or types of sedimentary rock and milk-based food products.

Later I heard him talking on a podcast about the Beatles singles and it started to make more sense. He talked about the way that those early records spoke directly to their chosen audience, teenage girls. The Beatles were the first boy band; but unlike their descendants, they weren’t manufactured. There’s a hidden appeal that undercuts the rational mind. It goes straight to the heart (or the loins) of the matter. Songs like “Please Please Me” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand” are a knowing wink to the girls who bought their records, a deliberate appeal to their unexpressed sexuality.

That same day I was on the bus from Canterbury to Whitstable overhearing a conversation between a couple of teenage girls in the seats behind me. They were talking about the Beatles as if they were all still alive, comparing the characters of the Fab Four, referring to them by their first names, and talking about their records in exactly the same way I’d heard teenage girls do back in the early-1960s.

I got off the bus and across the road there was a young boy, maybe nine or 10, singing “I Want To Hold Your Hand” at the top of his voice. That’s when I got it. The Beatles are still contemporary. They still speak to a young audience, perhaps a global audience, 60 years after they first stepped into our collective consciousness and altered our view of what pop music could do. They’re still vital and relevant. Like Shakespeare after the first Elizabethan age—already immortal before he died—the Beatles will live on in our imaginations for centuries.

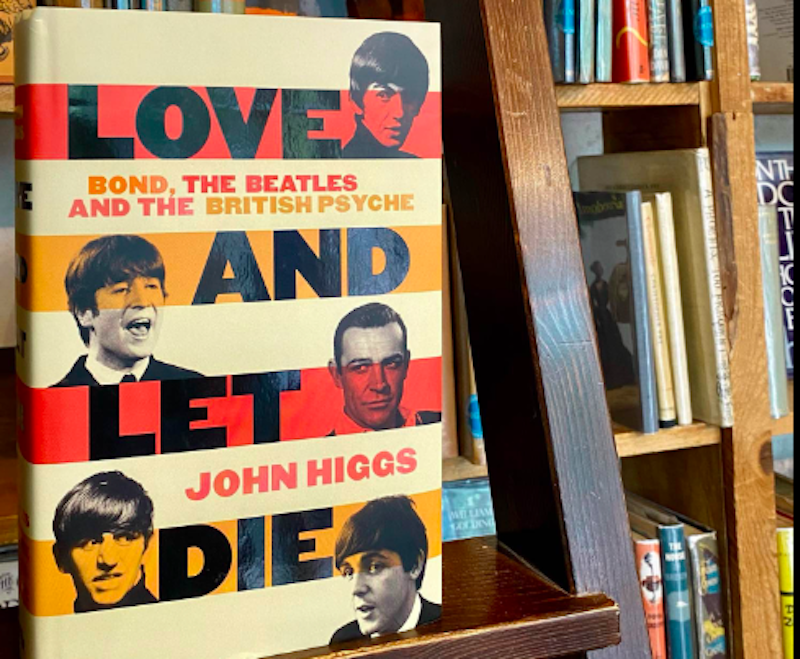

Reading Love And Let Die: Bond, the Beatles and the British Psyche is like a journey into the lost recesses of my own memory. I was nine when “Love Me Do” came out, but I wouldn’t have heard it till much later as it wasn’t played on the BBC. “Please Please Me,” on the other hand, released only three months later, was a sensation. After that the Beatles were never off the airwaves.

The history is so familiar to me that I’ve tended to take it for granted. It was the age I grew up in; but Higgs, younger, and coming at the material from a fresh angle, is able to cut through some of the myths. We get a new take on Lennon, the countercultural hero of the age. He did an interview with Rolling Stone magazine in 1970 in which he disparaged all the other members of the group and their collaborators. It was a mean-spirited attack upon his former bandmates and colleagues, born from his own pain and insecurity, in which he declares that he was the only genius. I bought into that idea: Lennon as the tortured genius, McCartney as his humdrum sidekick. But it was McCartney who wrote “Yesterday,” and who was the most dynamic and consistently creative member of the band. After the Beatles broke up and the world was forced to take sides, I chose Lennon. Reading Higgs’ book has helped me to reassess their relative merits and to see McCartney for what he always was: Lennon’s creative equal and the driving force behind his genius.

The book’s not a history. It’s a comparison between the James Bond franchise and the works of the Beatles: two of the biggest things ever to come out of Britain. Higgs makes his case in the introduction. Bond represents Thanatos, he says, the Freudian death instinct, while the Beatles represent Eros, the urge to open oneself up to love.

It’s like a dialogue between two opposing ways of relating to the world, which Higgs emphasizes by his use of a quote from William Blake: “Without contraries is no progression.” This allows him to look at a wide variety of issues, including the class system. Bond isn’t just death personified, he’s also the establishment. He has the establishment’s sense of entitlement and superiority. Like his creator, Ian Fleming, he went to all the right schools, had all the right connections, and spent his life defending upper-class privilege. He’s a sadist and a snob. The Beatles, on the other hand, are working class. They kicked down the door that blocked working class people from their full potential for centuries. They were bold, funny, sharp-witted and intelligent, as well as being almost supernaturally talented. Other working class bands followed, like the Kinks, the Animals, the Who and the Small Faces, and working-class actors and writers and artists in every art form. This was the time when Britain became, almost, a meritocracy. Anything was possible, if you were brave, energetic, committed and hard-working enough.

None of it has lasted. Today the working class are back in their box and poor again. The airwaves are dominated by affluent kids with family connections who can afford to buy the equipment to take up a career in music. The Beatles learned their trade in the dives and strip joints of Hamburg. They honed their skills as musicians by sheer hard work, sharing a single, dank room with bunk beds and doing several sets a day. That’s not to say that younger musicians don’t work hard: but they’re in a position of privilege where they can afford to fail. The Beatles never could.

Higgs tells a good story, which he heard from the writer Hanif Kureishi. Kureishi went to an all-boys school on the borders of London and Kent. In 1968 his music teacher insisted that the Beatles didn’t write their own music. It had to come from a more cultured background, like Brian Epstein or George Martin, he said. This reveals the attitude of the establishment at the time, and is a strange parallel to England’s other world-renowned genius, Shakespeare. Like the Beatles, Shakespeare’s creative originality has often been disputed, based upon the idea that a person from such a humble background couldn’t possibly have written such sublime works.

Higgs calls the upper class “The Norman Continuity Empire” and likens them to a cuckoo laying its eggs in another bird’s nest. There are two views of England here. There’s the geographical location, from which the Beatles emerge, complete with regional accents and a sense of community; and the ideology of Empire, which is actually transnational, and which supports an international network of secret correspondences in the form of concentrated wealth and power. The wealth belongs to a particular class, which has a particular accent, which you can recognize. It was the accent of the BBC at the time. The “Queen’s English,” or received pronunciation. It’s the accent of the aristocracy and royalty, of the boarding schools of Eton, Harrow and Westminster, and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. It’s the accent of Tory leaders and members of the royal family. In Britain before the Beatles it was the accent you had to adopt if you wanted to get on.

This upper class, non-localized England is where Fleming came from. It’s where Bond came from, despite Sean Connery’s disconcerting Scottish accent in those early films. There’s an irony here. While Bond was decidedly posh and English, his representative in the movies was a tough Scotsman from a poor working-class background.

The trick that’s been played is in convincing us that the ideological England of the Norman Continuity Empire shares the same needs and concerns as the geographical country over which it presides. Like Bond, the Empire is globetrotting, ruthless, psychopathic. Like Bond it has “a License to Kill.” It trades in arms and wars and will destroy anything that gets in its way. It will scheme, trick, lie, maim, murder. It’s also stupid. As Higgs says of its representatives: “Some of these people are so uninspired that all they can think to do, when they possess more money than they could ever use, is to try and make more. Typically, it does not occur to them to be embarrassed by this.”

Meanwhile, in the real England people are cut off from the money they need to put food on the table or a roof over their heads. The Beatles were a one-off. There will never be anything like them again. But there was a whole generation that followed in their wake, working-class pioneers, who in this modern world would find themselves removed from the source of their creativity by the struggle to survive. Britain, and the world, is poorer for that.

—Follow CJ Stone on Twitter: @ChrisJamesStone