When I reflect back on the years that I spent in Charlottesville, Virginia, I remember feeling that there were a lot of disturbing things going on for such a small town. In 2009, a 20-year-old Virginia Tech student vanished after being denied re-entry to a Metallica concert at John Paul Jones Arena and then attempted to hitchhike back to Blacksburg, which is 150 miles away. Three months later, her remains were found on a farm outside of town.

The next year, varsity lacrosse player George Huguely killed his ex-girlfriend Yeardley Love in a late-night drunken rage after forcing his way into her room and banging her head repeatedly against a wall. And then, just a couple of months later, Kevin Morrissey, the 52-year-old managing editor of the University of Virginia's esteemed literary journal, Virginia Quarterly Review, went to an old coal tower by the railroad tracks on a July morning and shot himself in the head just after calling 911 to report that a shooting had taken place. It would soon come out that Morrissey had felt that his boss, 38-year-old VQR editor-in-chief Ted Genoways, bullied him repeatedly.

It was a tragedy that took place at a location with a dark history. In a seven-year period beginning in 2003, there were two reported suicides in the area near the coal tower, six incidents of vandalism, five thefts from vehicles, two assaults, one rape, and a beating and attempted rape of a woman by three men. What drew Morrissey to that particular spot for his own suicide remains a mystery, as do so many of the circumstances surrounding his death.

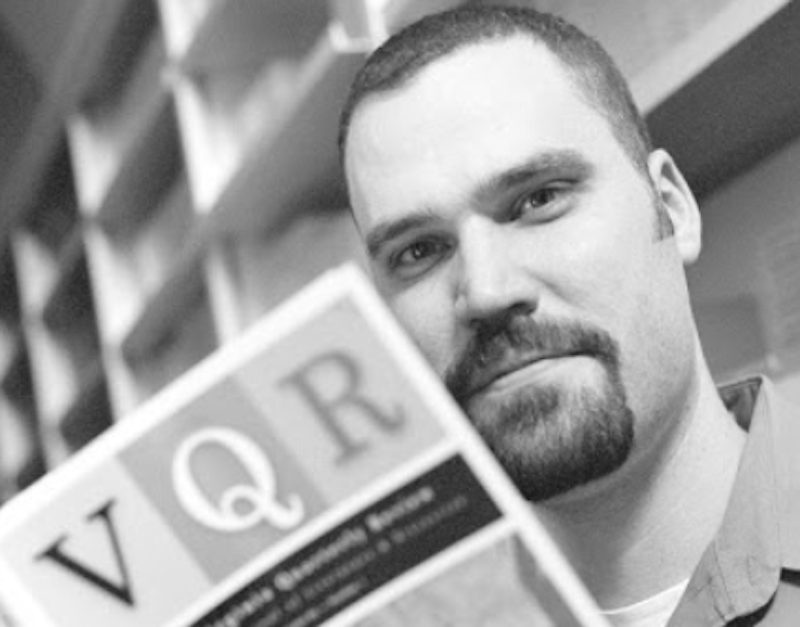

Genoways, a decorated poet who'd transformed VQR from an obscure black-and-white publication into a glossy journal that won six National Magazine Awards, was an unlikely villain. He denied having anything to do with Morrissey's death, but the Charlottesville media painted a much different picture of how he'd treated someone who'd once been his good friend. Genoways' photo was splashed all over the front pages of three local print publications, so everyone in town knew what he looked like. I recall getting the initial impression that he'd made Morrissey's life miserable and had contributed to pushing a vulnerable person over the edge. I also felt that a number of people didn’t intervene on Morrissey's behalf. This dovetailed with the impression I'd already formed of Thomas Jefferson's university as a place full of people who’ll put the institution and career considerations ahead of any one individual in need.

A major source of the ambiguity in the story behind the tragedy was Kevin Morrissey's cryptic suicide note: "Please tell everyone I’m sorry. I know they wouldn’t understand, but I simply can’t bear it any longer." Morrissey didn't specify what "it" was, but I do recall false media reports that he'd blamed Genoways in the note. Morrissey had had a long history of depression, which is what Genoways attributes his subordinate's death to. The editor-in-chief has publicly stated his belief that what brought things to a head was Morrissey's false impression that he was about to be laid off.

The Washington Post reported that one VQR staffer said Genoways had subjected Morrissey to a daily pattern of "insidious harassment, undermining, casual erasure of the person." The Post also reported that another staffer said, "Nobody killed Kevin but himself." VQR online editor and Morrissey's friend, Waldo Jaquith, went on NBC's Today show and said, "Ted's treatment of Kevin in the last two weeks of his life was just egregious, and it just ate Kevin up."

Morrissey, who'd become used to running the office on a day-to-day basis because of Genoways' odd, absentee management style, felt pushed aside when his boss gave a 24-year-old intern whose family had donated generously to the university's Young Writer's Workshop space in the editor-in-chief's private office and a salaried position. As a 52-year-old man with no college degree (although he'd scored a perfect 1400 on the SAT), he felt vulnerable, with no place to go.

It's confirmed that Morrissey called the university president's office, the UVA ombudsman, and the faculty and staff relations office to lodge complaints about Genoways, as did a number of other staffers. The gist of the response to the grievances was that Genoways was a creative person who wasn't expected to be a good manager.

Morrissey went to the coal tower, carrying his last will and testament, less than two hours after Genoways emailed him and took him to task for waiting nine days before forwarding him an email from a Mexican journalist (Genoways rarely checked his own email) with ties to VQR who'd been beaten up and had his family threatened. There were reports that Morrissey had felt that his boss was blaming him for putting the journalist's life in danger, and this was the "final straw."

It's unfair to say that Genoways is responsible for the death of someone who'd been clinically depressed for years, but that doesn't excuse his cruelty. Citing only "unacceptable workplace behavior," he'd once ordered Morrissey to stay away from the VQR office for a week and have no contact with his co-workers. Morrissey never knew what he'd done wrong. This act of bullying alone is enough to tell you that UVA should’ve intervened to stop such abuse, especially since officials already knew something had been amiss for years.

Any number of credible scenarios could be offered to explain what led to Morrissey's suicide, but here's mine, in a nutshell: VQR was the "baby" of UVA's president at the time, John Casteen. Genoways, who'd published a book of poetry by Casteen's son under the VQR banner, reported directly to Casteen, an unusual arrangement that set the stage for Morrissey to get bullied. The most powerful person on campus was partial to Genoways for reasons unconnected to his management style, and this offered Genoways substantial leeway in his behavior. Genoways didn’t attend the memorial service held for Morrissey. He resigned, of his own volition, from his VQR position in April of 2012.

As it happened, I sat next to Ted Genoways at a Charlottesville restaurant shortly after Morrissey had called for an ambulance to pick up his own dead body. My curiosity led me to strike up a brief conversation with him about how good the food was. That this "monster" who was supposed to have hounded a sensitive colleague into his grave couldn't have been more humble and friendly was unnerving. I remember wondering if it was an act brought on by the media pummeling he'd taken. I was surprised that he'd even show up at a crowded restaurant full of UVA people. Like so much of what has surrounded this tragedy, I couldn't make any sense of it.