While I was lounging on the poop deck of a Seastreak ferryboat, getting soaked by propeller wash and fending off other photographers on an overbooked ride to visit several NYC lighthouses, a thought occurred to me. I might’ve discovered my ideal job. Lighthouse keeper.

Give me a couple of hundred books, Internet, TV, radio, a Coast Guard visit once a week to get into town for groceries, and I’m happy. I’ve lived by myself for over 30 years and never had a desire to begin a family. Lighthouse keeping would get me even further away from the madding crowd in Little Neck. However, lighthouse keeping is, even more than copyediting, an extinct job description. Most lighthouses are automated these days.

I jumped at the chance to get closer to area lighthouses. There are some land-based lighthouses but most are too far off the coast for even my 18X zoom lens to do much good. When the Working Harbor Committee scheduled a three-hour tour, minus Gilligan and the Skipper, I signed up. Seastreak boats, though, are far from ideal for sightseeing since they’re primarily for ferry use. I persevered, but once I found a good spot on the small deck area, I stood my ground with teeth and nails. The boat traveled south from South Ferry as far as Sandy Hook Bay and then north again, past eastern Staten Island.

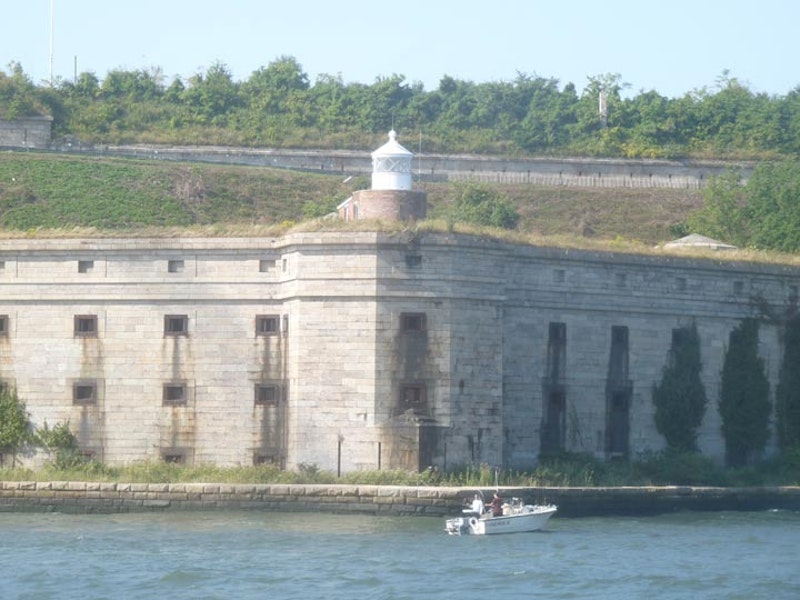

First on the itinerary was the lighthouse at Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island. It entered service on May 11, 1903 atop Battery Weed, and was active until the much taller lights were placed atop the adjacent Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in 1964. The light is 75 feet above water and flashed green for aviators and white for mariners. The Wadsworth’s light is similar in its situation to the Jeffries Hook Lighthouse, or Little Red, which adjoins the immense George Washington Bridge. There’s been a light tower in this location since 1828.

By 2002 the lighthouse was in decay and disarray, out of service almost 40 years. A lighthouse enthusiast, Joseph Esposito, organized a band of volunteers to restore it, and obtained a $27,000 grant for the Parks Department for its restoration. The light was switched on again in September 2005, four months after Esposito’s death.

The Coney Island Light, located in Sea Gate at the west end of Norton’s Point on Coney Island, was the last lighthouse in NY State attended by an actual keeper. Frank Schubert and his family lived in a house next to the light, and Schubert continued his watch until his death at age 88 in 2003, after 43 years as keeper and later, caretaker after the light’s automation in 1989.

One of two lighthouses in Brooklyn (the other was constructed on the Kingsborough Community College grounds in 1991) was built in 1890, flashes red and can be seen for 14 nautical miles. There are 87 steps to the top of the 61-foot tall light, which Schubert climbed daily well into his 80s. The design was copied from a now-razed lighthouse in Throgs Neck, Bronx.

The West Bank Light, raised in 1901, is located in Lower NY Bay approximately equidistant from Staten Island and the west end of the Rockaway peninsula. It’s 55 feet in height, stands on a J-shaped rock jetty, and works in tandem with the land-bound Staten Island Lighthouse near Richmondtown. Lighthouse life is not necessarily quiet. Generators for the lights and sound equipment hum all day and night. Then there are the storms…

“I met a lady once who was all filled up with what she called the romance of the lighthouse. She said she often longed to be a keeper and live alone in a tower on a rock far out in the sea, and have peace and quiet. She couldn’t understand why I snorted. Peace and quiet! A lighthouse is about the noisiest place in the world. Out there on West Bank, for instance, with a gale blowing. When I was there the tower rose right out of the water, with no footing at all around it, so the waves crashed against the whole tower; shook it until sometimes the mantles over the burners in the light broke. Sometimes the waves went clear over the gallery, and the spray over the light itself.”—Longtime West Bank keeper Ed Burge, in lighthousefriends.com

West Bank Light was finally automated in the early 1980s.

Southeast of West Bank Light and north of the tip of Sandy Hook is 54-foot tall Romer Shoal Light, raised in 1898. The lighthouse, and the shoals in Lower Bay, was named after the pilot boat William Romer, which sank in these waters in 1863. Colonel Wolfgang William Romer, a British military engineer (of German birth) sounded the waters of New York Bay in 1700 on order of the governor of New York. There has been a day beacon, and later, a lighthouse, on this site since 1838. Along with other lighthouses of the Lower Bay, it kept close watch for enemy vessels during World Wars I and II. The aforementioned Joe Esposito helped save it when there was a possibility that it might be torn down. The light is “in excess to the needs of the Coast Guard” and may be moved to the Staten Island Lighthouse Museum. The Romer Shoal light was severely damaged during Hurricane Sandy in October 2012; indeed, a nearby lighthouse, the Old Orchard Shoal Light, was destroyed by the storm.

A shoal is a sandbar, where the sandy bottom comes close to the surface. Lighthouses warn vessels away from them.

Found on the Sandy Hook peninsula, this is the oldest working lighthouse in the United States—it’s been in continuous service since built by Isaac Conro in 1764. It’s 90 feet in height and has used the same Fresnel lens since 1857. It was occupied by the British during both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, and was turned off during the World Wars because of its pivotal location at the entrance to New York Harbor. Though the light was automated as far back as 1964, the keeper’s house is the center for exhibits and is home base for tours.

A Fresnel lens design allows the construction of lenses of large aperture and short focal length without the mass and volume of material that would be required by a lens of conventional design. A Fresnel lens can be made much thinner than a comparable conventional lens—in some cases taking the form of a flat sheet.

This lighthouse was surrounded by several smaller beacons beginning in the mid-1800s. One of them was moved to Jeffries Hook in Washington Heights, Manhattan in 1917, and has been beloved to kids of many generations as the Little Red Lighthouse.

The brownstone twin lights of Highlands, NJ, on Route 36, were constructed in 1836 and can be seen from as far as 70 miles in the Atlantic Ocean in some atmospheric conditions (the official number is 22 nautical miles), making them the first sign of land in many cases. The Navesink twins were the first in the country to receive Fresnel lenses, first to use electricity, and the first wireless messages in the USA were sent between the Navesink Twins and the offshore USS Ponce. Marconi’s wireless tower was located nearby in Highlands. The Twins stand 53 feet tall and because they’re situated on a cliff they are 200 feet above sea level. Though the Coast Guard decommissioned the Twins in 1949 the north light still shines at night. The longtime keeper (1921-1952) was named Murphy Rockette.

Located in Raritan Bay off the coast of Wards Point, Staten Island, Great Beds Lighthouse was constructed to guide bay traffic around the treacherous Great Beds Shoal in 1880. Its conical shape makes it unique among the lighthouses of southern NY Harbor. It’s one of the tallest in the group as well, standing 60 feet tall. It can be sighted (best with a binoculars) from the new pedestrian paths in Staten Island’s Conference House Park. It’s technically in New Jersey, and its construction was delayed for two years while it was decided what state would claim it. In the 1880s, two consecutive keepers, George Brennan and John Johnson, died and disappeared, respectively, under mysterious circumstances.

The “Beds” in the name refers to oyster beds, which were plentiful in the waters surrounding the NYC area.

Located in Prince’s Bay, an inlet of Raritan Bay near Sharrotts Ave. and Hylan Blvd. The bay, and the surrounding neighborhood, was named for William, Prince of Orange, who became King of England in 1689. He was the William of William and Mary and the King Billy of the Irish nursery rhyme:

Up the long ladder and down the short rope

The hell with King Billy and God bless the Pope.

The current lighthouse was constructed in 1864 for $30,000, which was approved by Congress. The attached lightkeeper’s cottage was completed in 1868. Previous lights had shone from Prince’s Bay since 1837.

This lighthouse was deactivated in 1922, but the building’s been maintained by The Mission of the Immaculate Virgin at Mt. Loretto, a Catholic orphanage founded by Father John Christopher Drumgoole, the “newsboy pastor,” since 1926.

On our way back to Manhattan we passed The Robbins Reef Lighthouse in Upper New York Bay, east of Bayonne and north of St. George, Staten Island, and can be seen by daily ferry commuters. The present light was built in 1883 and was kept for many years by Kate Walker after her husband, John, died in 1886. She and her two children lived at the light and she’d row the kids to a school in Staten Island. During her time at the lighthouse she was credited with 50 rescues.

There has to be a movie in Kate Walker’s story, eventually. For the time being, plans are underway to construct a Kate Walker memorial statue that will be placed somewhere near the Staten Island ferry landing in St. George.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)