Ernest Hemingway elicits love and hate. A man full of inner conflicts, who created a mythical persona that eventually enveloped his being, Hemingway made a permanent mark on the American literature. A new documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, Hemingway (2021), goes beyond the persona that Hemingway created. In many ways, it’s a straightforward account of Hemingway’s life told in the typical fashion and style of Burns that audiences will be familiar with. At the same time, Burns and Novick make an incredible effort at trying to gather and understand Hemingway’s humanity.

Hemingway has been accused of too much masculinity. No doubt, today he’d be accused of toxic masculinity and promptly “cancelled.” Hemingway had a large and looming personality and a huge ego. But is that bad? In his essay, “A Tale About Ernest Hemingway,” Ralph Daigh points out that Hemingway had an “ego second in size only to Mt. Kilimanjaro and more abrasive than a coral atoll.” But, as Daigh writes, it’s also true that “an author’s ego is somehow tied to the seat of his creativity, and that without a prominent and vigorous ego there can be no big or superior writing. To excise the ego unduly is to castrate the author.” False humility is worse than an authentic egoism, so Hemingway can be forgiven there. At least when his writing is concerned.

The approach of Burns and Novick is balanced. No ideology runs through the documentary. Rather, we see presentation of fact and if there ought to be any interpretation in regards to Hemingway’s life, Burns and Novick leave that to the many interviewees that appear in the film. In particular, audiences and lovers of literature will be happy to see Edna O’Brien, Tobias Wolff, Tim O’Brien, Mario Vargas Llosa, Mary Karr, as well as a wide variety of Hemingway scholars make an appearance as they try to put together the puzzle that’s Hemingway. Especially poignant are the moments of his son, Patrick, speaking about his father’s presence and absence, kindness and cruelty, all with great sadness.

We learn about his overbearing mother, who made Hemingway and his siblings feel guilty about the fact that she sacrificed an opera career in order to take care of them. Hemingway hated her, calling her “an All-American bitch.” This hatred particularly intensified after his father committed suicide, which Hemingway blamed on his mother. The dark specter of suicide, always accompanied by extreme depression, was always present in Hemingway’s life. One could say that everything Hemingway did, every decision he made, was because of this one event and his own interior feelings that always resulted in depression, and later in life, in paranoia and psychosis.

For this reason, Hemingway sought out life. To forget about death, he rejected an ordinary existence and this is perhaps what scared him the most. He made many impulsive decisions, like being married four times, and all the relationships (particularly his marriage to Martha Gellhorn and his last wife, Mary Walsh) were volatile and unsustainable. He’d eventually become unkind and cruel to all the women he was with. When he got tired of one, he found another.

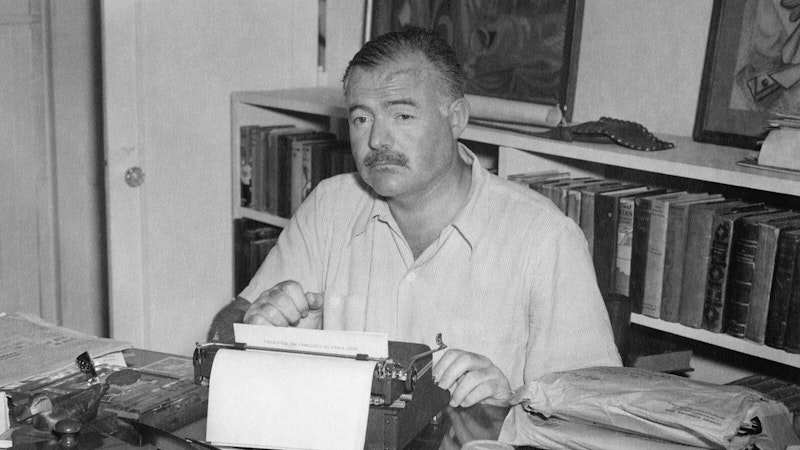

Trying to prove that he was a man was one reason for being. He quickly became famous as a writer who seeks great adventure, like safaris, and the more he sank into the myth, the more he was unable to see who he really was. Yet, Hemingway wasn’t without honor. He was in two world wars, and witnessed evil and death, which contributed to his depression later in life. Burns and Novick tie this in beautifully with his persistence to write. Hemingway was never satisfied and always wanted to push himself as a writer to the next level. He persisted, especially with his first novel, The Sun Also Rises (1926), and as he got older, with The Old Man and the Sea (1952). Every true writer will affirm that it isn’t easy sitting down and facing the blank page, and Hemingway knew this fear intimately, especially later in life.

On one hand, it isn’t surprising that Hemingway committed suicide in 1961. Toward the end of his life, he became increasingly paranoid and was treated with electro shock therapy in order to cure his depression. But this left him blank. He couldn’t compose sentences anymore.

There’s also a family history of volatile behavior, not to mention his father’s depression and suicide. It’s easy to look at all this from a purely clinical point of view; however, this approach often reduces a human being to a jumble of psychotic mess. Burns and Novick don’t do this, and this is what makes their effort noble. A balance is achieved in the documentary that never sacrifices Hemingway’s greatness as a writer and as someone who has looked into the human heart so deeply, and with such beautiful and perfect brevity.

At the same time, as Mary Karr points out (and judging from Mary Walsh’s letters to Hemingway), it’s his alcoholism that appears to be the primary mover as Hemingway slouches toward death. There’s nothing remotely romantic about alcoholism. It makes a person depressed and less productive. Paranoia, which Hemingway experienced later was a clear link to alcohol abuse. Would he have created more if he didn’t drink? Would he have had a clearer mind? Yes. Would he have become a kinder person? Perhaps. But the fact that Hemingway was capable of producing so much great writing, and lived through turbulent times, while his boozing escalated, is a testament to his strength as a person.

Despite the myth of “Ernest Hemingway” that was mainly created by Hemingway himself, an authentic human being emerges now and then. The authenticity isn’t found in showing how much chest hair he has (which he actually did to a critic that denounced him), or how much he can drink, or how many lions he can kill. Hemingway’s personhood and authenticity are felt in his books, as he metaphysically bled on the pages he wrote, and as he presented, with an unparalleled clarity, the interior conflict and affairs of the human heart.