Not long ago, my friend and colleague Emina Melonic—one of today’s most insightful film and cultural critics—wondered on a social media platform why there’s such a dearth of original and absorbing novels today. It was a loaded question, I thought, and perhaps off-hand, for although the book publishing industry is in tatters, for the curious reader there’s plenty of great titles. (Although the fact-checking and research departments are gutted, just like newspapers and magazines. It’s more egregious in a book, since the gestation is much longer than, say, a 2500-word New Yorker article. In a recent novel I liked a lot, the author’s narrator referred to attending a Smiths concert in November of 1987, months after the band broke up, which left me momentarily aghast until I remembered what year it is.)

I answered her query, citing the work of Ottessa Moshfegh, Fredrik Backman, Anna Burns, Jonathan Coe and Tracey Lange (her debut novel, We Are The Brennans, about a sprawling Irish family in New York, is excellent); my son Nicky chipped in with Tao Lin’s Leave Society and though I didn’t follow the thread I’d guess Emina received more suggestions for recent novels than she has time to read. (I’m reminded of the specific time-travel film About Time in which Bill Nighy’s character, like all the males in his family, can visit past periods of his own life. He tells his 21-year-old son (Domhnall Gleeson) that one of the most pleasant advantages of this ability is not accumulating money—which has led to misery among some relatives—but reading and re-reading, with unlimited time, any number of British writers, especially Dickens.)

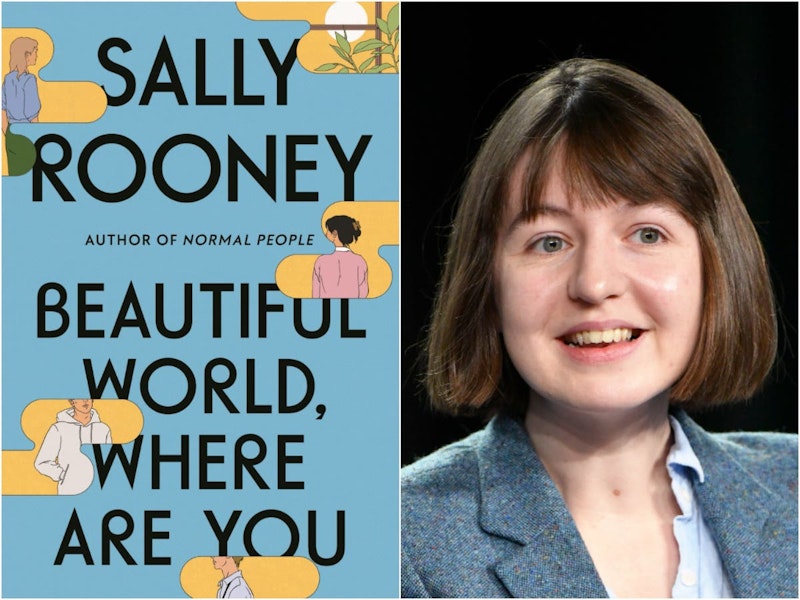

That brings me to Beautiful World, Where Are You, the new novel by Irish author Sally Rooney, whose fine Normal People (2018) made her a literary star before turning 30, and presumably rather wealthy, not just from book sales but the BBC/Hulu 12-part adaptation (which wasn’t notable; I dropped off at episode five). I zipped through Beautiful World upon its release, and was initially satisfied. Rooney, as opposed to so many writers today, composes clear, not-a-wasted-word sentences, is often funny, and refrains—aside from incorporated text messages between two characters—from the Internet-shorthand that mars so much writing today. It could be I was pre-disposed to like the book, given the criticism in British newspapers that this was another novel from a white woman of privilege—and the attendant tut-tutting from people who undoubtedly hadn’t read the book—and therefore must be at least metaphorically burned or banned.

Yet, upon reflection, I wondered whether Beautiful World—Rooney’s apparently an “avowed Marxist”—was a clever satire or should be taken at face value. My son Booker, who also praised Normal People, was adamant that it wasn’t satire, and, in fact, just a bad novel from a young woman (about his age) whose well of compelling prose had run dry. I went through the book again and revised my first dashed-off opinion. It’s not at all bad—unlike so many other novels, Ben Lerner’s work comes to mind, I didn’t toss it after 75 pages, and was curious about how it’d turn out at the end. But it’s flawed, and though the book will likely net another TV contract for the Marxist, it won’t be remembered. Rooney hasn’t yet pulled a Sam Lipsyte, whose earlier Venus Drive and The Fun Parts were at turns masterful, but has since capitulated to the “proper” cultural norms (he teaches at Columbia University) and his 2019 book Hark was atrocious, but she may be veering that direction.

Beautiful World follows four main characters—author Alice, her best friend Eileen, who works at a literary publication, high-level civil servant Simon, and factory worker/reprobate Felix—mostly in Dublin, but with spells in France and Italy, and their various travails. Except for Felix, who’s not an intellectual, maybe not even “street-smart” but is humorous throughout, such as when he questions Eileen about why she went to college only to land a job that paid far less than his, none of these somewhat young people are likable, and their world-weariness is off-putting. There are many sex scenes in the novel, but they’re clinical, sterile, as if Rooney was on auto-pilot, including them because that’s what she’s supposed to do, even if they’re not really believable.

Simon, five years older than Eileen and Alice, is presented as a handsome, bright professional who also happens to attend church regularly, which at first is the source of disbelief from the others, and then perhaps as the sensible belief of a “normal person.” On the surface, Simon has the most going for him—Alice is wealthy from her two books, but is misanthropic, alternately mean and gracious, and had a breakdown during a book tour and was subsequently hospitalized—but he’s an indecisive wimp, who takes his professional glad-handing into his vacuous personal life. Eileen, who’s pined after Simon since she was a child, and has since consummated that longing, weeps, and weeps, at the most incidental misunderstanding or paranoid thought, and you’d think maybe she could use a month or two in therapy and given a regimen of happy pills.

The conclusion is at once predictable and jarring, since it’s not what you’d expect from Rooney.

Writing in The New York Times, novelist Brandon Taylor, in a mostly positive review, says: “That is, ‘Beautiful World, Where Are You’ is carefully formless and its characters are fluent in our lingua franca of systemic collapse, that neoliberal patter of learned helplessness in the face of larger capital and labor systems.”

Here’s a passage that speaks to self-consciously “tortured” intellectuals. Alice, in a text to Eileen, explaining how she’d become the kind of person she now “energetically despised”: “It was important to me then to prove that I was a special person. And in my attempt to prove it, I made it true. Only afterwards, when I had received the money and acclaim which I believe I deserved, did I understand that it was not possible for anyone to deserve these things, and by then it was too late… I don’t say this to slight my work. But why should anyone be rich and famous while other people live in desperate poverty?”

I don’t think that “lingua franca” is unique to the current world. Go back 50 or 60 years and I doubt Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer—not politically compatible—would ask Alice’s (a loose stand-in for Rooney) question.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955