When you reach a certain age your grandparents start naturally dying off. It’s part of life, sure, but if you like your grandparents, as I do, seeing their minds still sparkling while their bodies melt into pools of jelly—held up each day by beeping machines, artificial joints, stents, bypasses, transplants, implanted boxes, catheter bags, private nurses and a horse’s ration of pills—makes you uneasy. Over a mug of retirement community split pea soup (burnt tires + Splenda) grandma and grandpa tell you, with little smiles, that everyone they went to high school with, shared a first smoke, went to prom and made out with, everyone they went to college with, everyone they’ve ever worked with or traveled with or roomed with, all the pretty ex-girlfriend’s in Union City New Jersey and the bridge partner’s in Buffalo—are either dead or hooked up with more wires than a robot.

From here, things progress in a Edgar Allan Poe poem-like fashion: I start visiting their wired quasi-corpses in dimly-lit hospitals or “care-centers” or “wellness centers” or “elder clinics” whose hallways are clean and white but echo with screams and moans. When they can’t make it out of there, their bodies get moved into caskets or ovens, and soon, we’re eating cake over their gray flesh or gazing at a jar filled with dust while someone is making a speech about how they used to be when none of us knew them. People parade by the bodies, nodding at the dead, muttering goodbyes, patting their stuffed chests, and 10 minutes later, over more food, they’re blithely discussing what football games are on later. Even I can admit that there’s a secret elation that sweeps over you when you go to a funeral. I’m still fucking alive, you think to yourself as they lower the poor rotting sap into the ground. It’s almost like a second chance. And I am still YOUNG, how about THAT?

As these people you love fade away, it somehow happens so fast and takes forever too. You want them to stay, selfishly, so you can hear their dirty stories about 1940s Coney Island, so they can shamelessly brag about you to their friends, but you want them to go so they don’t have to be so tired and lonesome and bored and in pain. Two years ago my grandfather in New York succumbed in his wife’s arms on the living room floor—she tried to catch him but couldn’t—so they danced there together, a married couple of 50 plus years, falling down like kids—and what could she do, his body refused to hold his blood any longer, refused to know how to stand, how to move. For months, grandpa looked like a pumpkin dropped from a parking garage that refuses to pop no matter how high the fall. He grew and grew and grew until he was so embarrassed he knew he had to go before he blew up all over the nice furniture.

My grandfather in San Diego on the other hand suffers indignity after indignity but makes more comebacks than Rocky—in the simplest sense, he just plain refuses to leave this world. Contracting polio as a child, surviving a “cripples sanatorium,” the iron lung and doctors who said he might not live through the night, let alone walk, he rose to become the head of aeronautics at GE and an important fixture in the department of defense under Nixon and Ford. He later joined the boards of corporations even as the echoes of his childhood malady began to haunt him, twisting and weakening his muscles cruelly so he leaned sharply to one side and could barely walk or look upright. As his body coiled and turned against him as an old man, he responded by inventing, designing, and patenting a one sided walker so he could zoom through executive dining rooms by simply leaning into the momentum of his machine.

But now it looks like his game is up. Every month or so we get some ominous call to prepare ourselves—he’s not looking good they say, this could be it. And then it passes. It’s a roller-coaster cycle—he’s fine, he’s happy, then he falls, he goes in the hospital, (seemingly for the last time), then returns victoriously to his chair by the TV at home. Then he can’t breathe, then he can’t remember, then he falls again, harder, with blood, then he doesn’t eat, then his heart races, his lungs fail, then he goes to the hospital again. Again he responds and comes back home, then gets stronger, sassier, he talks trash to the nurses, comes on to grandma, but then he can’t go to the bathroom and he doesn’t eat again, he gets weaker, smaller, gets afraid, can’t sleep, can’t be alone, goes back to the hospital, responds to the meds, comes back again, determined to stay out of that shithole longer, holding court on his hydraulic chair, destroying his grandchildren at gin rummy and cribbage, watching Jeopardy! every evening and muttering the answers sagely under his breath. It makes you wonder what the hell it’s all about.

*

Okay, so I’m on my death wave. I need a pick me up, a shot in the arm. Don’t ask me why, but more often than not, it’s a bit of darker blackness that brings me a smile in the night. Movies, songs, books, give me death and make it dark and honest and nasty. That’s what I want. That’s what hits me in the sweet spot. And like a great tune that nails what you’re feeling in an exact moment, a tough, honest work about death itself can somehow really make you feel better when you are in the thick of it.

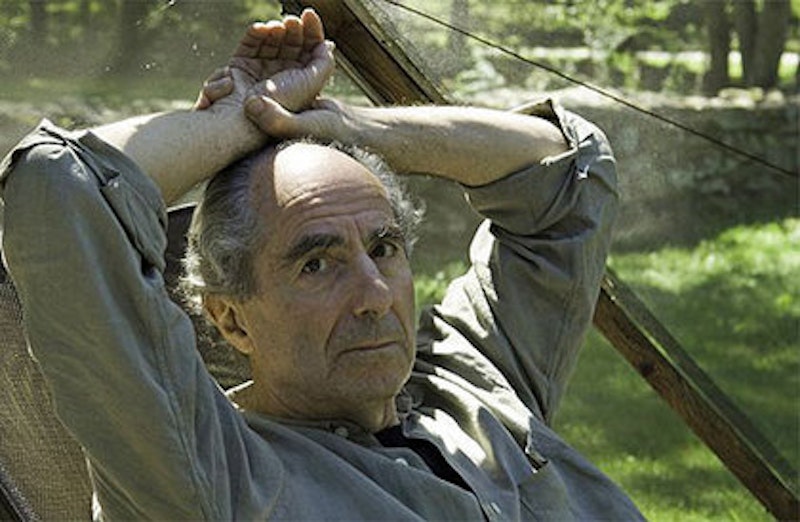

Philip Roth’s Everyman is that work. As the jacket tells us, Roth took the title from “an anonymous fifteenth century allegorical play, a classic of early English drama, whose theme is the summoning of the living to death.” What struck me about the story was its unwavering concentration to the task at hand: to remember and express how it feels to be sick and to die and to see the ones you love grow sick and die. One malady in a son is recounted with vivid detail in the father—and Roth expertly details the pain and bewilderment of mortality by recounting the lives backwards, starting with now, the children grown old, then back with the parents, then back to now—with undiagnosed appendicitis being a poignant shared terror. Both father and son, generations apart, return home after the same surgery, weak as babies, trembling with gratefulness that they survived, but frightened at how quick and easy they could have disappeared. Roth nails the existential helplessness that life gives us: we don’t know why we are here, where we came from, how long we are going to be here or where we are going after we’re gone. And there’s something horrible and beautiful in that mystery.

What’s so haunting is that Roth’s protagonist could be any of us. At different times he’s an imperfect brother, husband, father, son, kid, teenager, lover, adulterer, friend, colleague, artist. He grows up the son of a jeweler, a boy who worships his father, who tries to have a family of his own and instead follows his lust, follows his joy until he’s thrice divorced and alone, siblings and lovers spread across the continent like shipwrecked sailors, some loving him despite his addiction to crashes, others keeping their resentment thick and hard in their hearts, no matter how hard he tries to make amends.

He thinks he can be a freewheeling painter after a powerful but controlled career in advertising—but finds that it’s warm, human contact that he needs, not art. Someone to sit with him during a procedure. To be there when he wakes up. Someone to give a shit when the knife comes down. That’s what it’s all about isn’t it? Caring for someone and having them care about you, no matter what you’ve done?

Gradually, we learn about his family, watch them die, watch them thrive as he dies, watch him resent their health. And then we meet his wives, his loves, the excitement of their beginnings, the vivid, energetic sex, the courting, each body’s glories, and then what unraveled, the lies, the tearing words and despicable acts—then the next excitement, the next love that appears out of the ether as if to restart the heart—then that love unraveling, that love dying, that body withering until, at the end, there’s no more to undo, no more to destroy, no more to love. It’s just him, just us, alone. One body. A world unto itself, unable to control why or how it works or when it will stop working. Like a good engine after decades of use, it is impossible to avoid the rain coming—impossible to avoid the final rusting away to uselessness in an empty lot.

A recurring phrase in the book seems to summon up the honest, yet comforting message of the book. A maxim the father of the protagonist told his children was this: “There’s no remaking reality. Just take it as it comes. Hold your ground and take it as it comes.”

When death is your blues, somehow that does sounds awful nice.

In the Mood For Death?

Philip Roth's stunning Everyman may help you get through your more existentially troublesome moments.