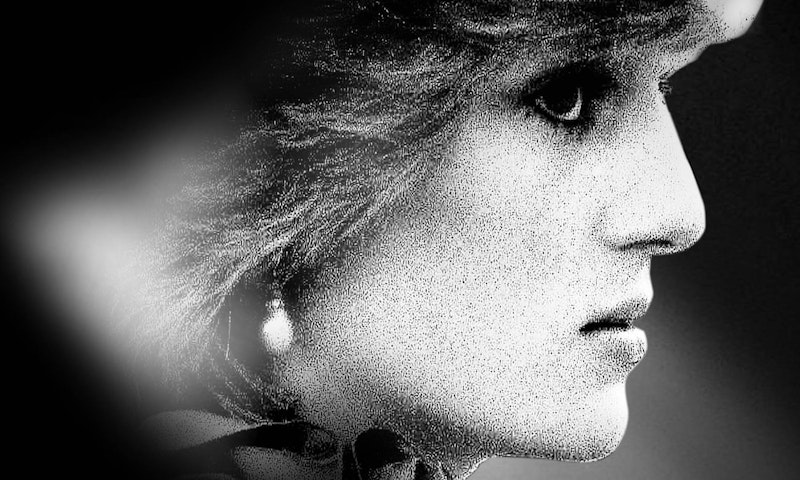

It’s 25 years since Lady Diana Spencer died, in a car accident in the Pont de l'Alma tunnel in Paris, while pursued by her paparazzi tormentors. She was in the company of her lover at the time, Dodi Fayed, who was also killed. I heard about the anniversary on the radio. The announcer was asking her guests where they were when they first heard the news. Everyone had a story to tell. It’s one of those epoch defining events—like the death of John Lennon, say, or the 9/11 attacks—where everyone has an exact memory of what they were doing at the time.

In my case I was in Bristol, in the Southwest of England. I’d been to a punk gig the night before. The band were called The Living Legends and they were fronted by this little bald guy with round, bottle-bottom glasses and an aggressive snarl. The songs all seemed to glorify violence in some form—I remember one about the blood of the ruling class flowing in the gutters—and it wasn’t at all clear whether the singer meant the words seriously, or whether they had a humorous intent.

There’s a Living Legends record available on YouTube. It’s called The Pope is a Dope and it’s chanted rather than sung. The first verse goes like this: “Only a mental defective would issue a papal directive against the use of a contraceptive.”

The singer’s name is Ian Bone, and he’s much more famous as a political figure than as the lead singer of an obscure punk rock band who’ve probably seen better days.

I’d met him a few years before, in London, at an anarchist book fair when I interviewed him for a BBC radio piece. The interview took place in a shop doorway just around the corner from the pub where we’d spent the last several hours drinking beer. I began a long-winded introduction, referring to him (as he was known by the press at the time) as "The Most Dangerous Man In Britain." He cut in on my self-indulgent monologue saying, "I thought you were supposed to be interviewing me, not talking to yourself." That irritated me and we squabbled. I have to admit that he out-maneuvered me on every point, which irritated me even more. It wasn’t a good interview.

Later I got to know him a little better. He was always funny: fast talking and confrontational in his approach to politics. It was unclear how serious you were meant to take his often blood-curdling rhetoric. In his time he’d published several successful newspapers, which had large circulations. The most famous was Class War, whose logo and masthead, featured a skull and crossbones dripping blood. You can see samples of Class War cover art here.

As time went on the newspaper became an organization and a number of campaigns took place under its banner. The most memorable of these was Bash the Rich, in which members of the group harassed participants at events, like the Henley Regatta, where wealthy people tended to congregate. Here’s Ian Bone talking about his politics and about Henley Regatta in a 1990s documentary, from the period I knew him.

“Bash the Rich” is also, coincidentally, the name of his autobiography.

So that’s where I was on the evening before Princess Diana’s death, at a pub in Bristol with Bone. It was his 50th birthday. I was living in a van at the time, a converted ambulance. It was parked in the pub car park, so I didn’t have far to go to crash out in a drink-induced stupor at the end of the evening. The following morning I went to Bone’s house. It was full of his friends from the night before. I had to wake them up as they were all hungover. We were soon drinking coffee which helped relieve the symptoms. I went to the bathroom and there was this sudden commotion next door. People were cheering and stomping their feet. I went out to find out what was going on.

Bone and his friends were dancing a jig, spinning round and round, arms interlocked, like people at a square dance. They were singing, “better red than dead! better red than dead!” over and over rhythmically, while shrieking with laughter.

“What’s going on?” I asked, confused.

“Di’s dead!” they laughed.

It took me a minute or two for the news to sink in. “Pardon? Who’s dead? Di, did you say?”

“Yes and Dodi too.”

It didn’t make any sense. How could Di be dead? What happened? And how come I was at the only house in the UK where the news would be greeted in such an extraordinary manner?

After that we went to the pub. It was the nearest pub to Bone’s house, called, appropriately enough, The Princess of Wales. I’m not sure the pub wasn’t specifically chosen for its name. The sign outside had a picture on Diana on it and the walls were covered in photographs of her. The place was in a state of shock. There was a TV on with rolling news about the event. The whole nation was in mourning. Funereal waves of desperate sadness and despair. People wailing on camera. Everyone in the pub was watching the news in stunned silence.

Except at our table. At our table they were telling “Dead as Di and Dodi” jokes and laughing, threatening to turn her photo around so that it faced the wall.

“Don’t Ian,” I said. “You’ll get us killed.”

I’m amazed to this day we weren’t set upon and beaten to a pulp. There’s something about Ian Bone. Either he’s charmed, or he’s under protection. It’s like no one dares to confront him, as if he’s so outrageous that other people can’t quite grasp what’s going on, as if the cognitive dissonance of having someone laugh at Di’s death, in a pub named after her, under a photograph of her, on the day she died, is so great that it simply won’t register in their brains.

After the pub we went back to his house. A record came on the radio. It was San Franciscan Nights, by Eric Burden and the Animals.

"Old Child, Young Child, feel all right, on a warm San Franciscan Night."

"Listen to that Ian," said Bone’s partner, Jane. And she began singing along with it. Bone was embracing her from behind, singing along too, his chin on her shoulder, his face next to hers. They were embracing and swaying and singing a sweet hippie love song together. Love and peace and flowers, not blood and death and the revolution.

"Wait a minute Ian," I said, mildly bemused, "you mean—have I got this right?—you were hippies? Not punks, hippies?"

"Of course," he said. "It was such an optimistic time. We really thought we were going to change the world."

I fell out with Bone in the end. It was after an argument about the use of violence as a political tool. This was around the time the anti-globalization riots in Prague, where British punks with Union Jack jackets were seen throwing rocks at the opera house. This just seemed ridiculous to me. I decided that the reason Bone has never been jailed is that, while he isn’t actually an agent provocateur, he does everything that an agent provocateur would do, which is why the establishment leaves him alone. Why pay people to encourage mob violence so you can crack down on it, when Bone does it all for nothing?

Class War is like a cartoon political organization, all puff and no policies. They make a lot of noise at demonstrations, usually sneering at everyone else on the left, throwing firecrackers and insults, but never achieving anything. They’re like the errant children of the revolution gone feral, more interested in creating mayhem than making sense.

As for Diana, the outpouring of grief at the time was extraordinary. I went to one of the places where people were gathering in remembrance of her. It was like a sea of flowers, thousands of bunches laid out against an iron fence in the middle of my home city of Birmingham. Every town and every city had a Di memorial spot where the crowds would gather, to leave notes of remembrance, floral wreaths or cuddly toys. Diana was much more powerful in her death than she’d ever been in her life. Her life and death took on a mystical status, transforming the British psyche overnight, from diffidence and reserve to grand displays of public emotion. Her funeral became a kind of national catharsis, with tens of thousands of people lining the roads to watch her coffin transported, people throwing flowers at the hearse along the way. The floral industry must’ve had its best days ever in those few weird, traumatic weeks.