Years ago I worked for a guy who was just terrible. He was a brat, 34 years old but an overgrown, ill-natured little boy of the spoiled suburban type, more specifically of the sort that’s supposed to be gifted in some way. I imagine Walt (as I shall call him) being inflicted on dinner parties in Connecticut back when he was a child. Maybe he delighted them with his turns of phrase à la S.J. Perelman. Maybe he played jazz solos on his clarinet. I know that one time he recited Gilbert and Sullivan at me. He stuck a foot behind the other foot, tilted his head, and began spouting. Quite possibly he tucked his hands behind his back, schoolboy-style, to underline what a show he was putting on. I stared at him and felt trapped. No polite response was possible. I think I dropped my eyes to the floor and kept them there until he got disgusted and left.

Aside from being needy, Walt was mean. He announced to Timothy, the new fact checker, that he could tell Timothy wasn’t going to fit in. He told Teresa, our assistant production editor, that she had obviously never worked for a major operation, nothing as big as the medium-rank business magazine that employed us. “That one,” she said. “On my first day he wanted me to know I was garbage.”

You'll notice that he liked to pick on junior employees who had just been hired. It happened to me too. During my first or second week, Walt planted himself across my desk as I ate my Japanese takeout. He forced me into a series of Simon Says motions: He lifted his hand, I had to lift my hand, and so on. He did it in a spirit of experimentation, to see what he could get away with. I say “forced” and “had to,” but that’s not the case. I was just too nervous and off-balance to face him off. That was the fun of it, for him. The event was like a deluxe version of a staredown contest, and anybody who wants a staredown with me isn’t really looking for a contest. The grace note was that I have trouble with left and right; they switch around on me. At one point, let us say, I lifted my left hand after Walt lifted his right. “No,” Walt said. “That is not your right hand.” He said it with an eye roll.

As it turned out, he was even more defective. Walt was clever about puns and grammar and puzzles, and he wrote good prose in classic copy-editor fashion: trim, streamlined, smoothly turned. But he had no curiosity. I remember he was pleased with himself because every day, first thing, he sat at his desk and read the front page of The New York Times. He figured this was his executive summary of world events. The Times was the best paper, and the front page was where the Times put the articles that counted, so therefore… Walt liked to expand on his cleverness this way, his ability to escape getting bogged down by the inessential. When talking about his Times habit, he didn’t realize that he was displaying a limitation. That's because he didn't know curiosity existed, that it was something other people had even if he didn’t. The whole business of finding out, of wanting to know what you didn’t already know, was a blank to him. One day he mentioned, offhand, that he never read the articles’ jumps, just the bits on the front page.

His defect soon came to bear. He was a young blood at the magazine, brought in because he was buddies, in a father-son way, with the magazine’s new editor-in-chief. They had worked together before, and the editor was an old colleague of Walt’s father, who was something big (in an emeritus way) at The New York Times. The magazine was going to be Walt’s big break. His aim there was to make the jump from copy editor to the real thing, the sort of editor who assigns stories and works them over. During our six months together, he took that jump and failed. He had a big feature article to work on, and what he handed in was an encyclopedia article with puns. The subject was advertising, just advertising: in ancient times, Medieval times, Boswell’s London, today. The last sentence was something on the order of “As the years stagger on, advertising is bound to keep staggering us as well.” Maybe not that bad, but the same idea. It was the kind of sentence that comes at the end of story-of-whatever articles, and such articles occur in children’s encyclopedias, not in feature magazines.

You’d think the editor-in-chief, Walt’s old mentor, would have noticed this article coming and dropped a word about the need for an angle. Apparently he didn’t. Instead he waited for the thing to reach his desk, read it with surprise, then killed it and left Walt to tell the freelancer. I suspect the editor was preoccupied, since by this point the owners were getting impatient about circulation. At any rate, one afternoon I looked up and found Walt goggling at me. A bit earlier he’d been going on about his jazz clarinet repertoire and Woody Allen’s habit of playing jazz clarinet at a midtown pub every week, news that the rest of the world and I had absorbed years ago but that Walt dispensed as his personal bombshell. “Mr. Allen duly presents himself and performs said numbers with a will,” Walt had said at one point, because he brought to conversation touches of style (“this I now did,” “retorted promptly,” “decided quite sensibly”) that made me want to bite my arm. In short, he’d been the same as ever. Now he was back and he was shaken. The editor had just given him the news.

“He said it had nothing to say,” Walt told me, and his voice trembled. “That isn’t true. You read it. Did you think it didn’t have an angle?” I just managed to shake my head.

Walt left the magazine soon after. “If he can’t be the golden boy, he quits,” summed up Trish, my colleague in the copy department. She was his protégée and had worked for him at his place before this one, a controlled-circulation magazine where he had been number two on a staff of four. She told me how he’d switched jobs, moved out to Long Island so he could work at Newsday, the big paper there. It had been a jump for him, one that took about a year to perform. Newsday had interviewed him and tried him out, then tried him out again, and finally he received word. The day he left his old place, he revealed his master plan to Trish: amass big-daily experience, and then become managing editor of The New York Times.

A week later he was back in the office of his old boss. He wanted his job again. What had gone wrong at Newsday? Small things. He made a mess of checking some graphic that involved a lot of data. Somebody yelled at him, either for that or something else. When he brought up involved points of grammar, real dazzlers, people got irritated. Finally, on Friday afternoon, he walked out. He was standing there as the minutes ticked down to deadline, a mess of some sort had developed, and Walt’s feet shifted about and he headed for the door.

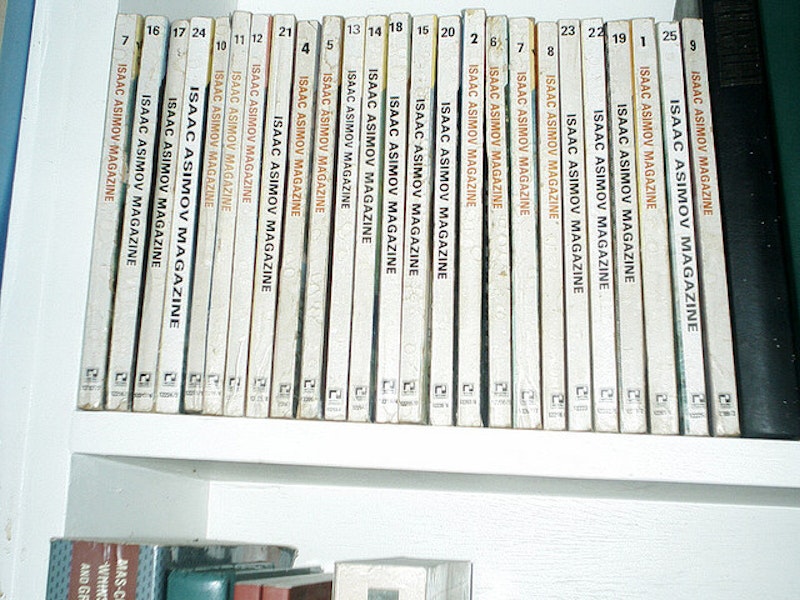

Another episode had been related to me by Walt himself, back before his advertising article disaster. I had heard, perhaps from Trish, that at some point he had sold a story to Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. I asked him what it was about. Walt shifted into his declamation pose and his voice lifted. “It was called ‘How the Venusian Farmer’s Daughter Made Two Zerkees and a Donard, and What She Did With Them,’” he said. “And that is what the story was about.” Understand that I’m not giving the exact title, but it was arch and involved and contained a stock element from an old joke. I think he stood on his tiptoes as he recited it.

Even so, Isaac Asimov’s magazine! I asked what happened after he sold the story. At this point Walt and I shared what has to be called a moment. If you’ve ever been a copy editor, you know that life is a trap designed to keep you from being a writer. So it seems anyway. Looking back, I think Walt and I shared this understanding. He didn’t insult me or fob me off when I asked. He answered my question and did it with the air of somebody owning up. He told me that the story, the first he’d ever written, had been the opening shot in his campaign to become a science fiction writer. After it sold, he kept up his campaign. He went home to his apartment after work, sat down at the typewriter, and wrote more stories. “And I mean I really did it,” he said. “I put in my three hours.” He said this shaking his head, because the stories all got turned down. He sent them off to Asimov’s, and Asimov’s sent them back. Walt had kept it up for a dozen stories or so.

For once I sympathized with him. I saw the episode as he did, as an example of the writing business and its cruel, mysterious breaks. Trish set me straight after he left the room. “What a wimp,” she said. “I told my mother that story and she said, ‘What a wimp.’” I had to accept her judgment on faith. Whatever stupidity Walt showed in this story, I shared it too. Only years later did it occur to me that Asimov’s wasn’t the only place that ran science fiction stories. He could have sent his stories around, scratched together a following. That’s how you get a career going. More simply, it’s how you keep doing what you want to do even if the nearest authority declines to encourage you. Walt thought he wanted a career, but not really, and I don't think the idea of doing something for love ever occurred to him. He just wanted someone august and important to single him out. He lived his life so he could be awarded a badge.

Trish kept me up to date about Walt after he left the magazine. He was coming unglued sitting around his apartment. On the other hand, he couldn’t buckle down and take another job; nothing suitable seemed to present itself. He was practicing his clarinet five hours a day, and then he wasn’t practicing it. He started therapy; he turned up at his parents’ house, shaky and in tears. This was either before or after he accepted the job of managing editor at either Consumer Reports or Consumers Digest. I forget which, but it was a good job to have if you knew grammar but didn’t understand the reason magazine articles exist, and a good place to be if you wanted security and pay. The place was a lifer’s institution, like The New York Times, and high-prestige in its way. But that way was, itself, pretty humble—nothing like that of the Times, at least. Walt was anguished by the thought of taking the job. He accepted, spent a dreadful weekend as his start date approached, then called Monday morning to say he wouldn’t come in after all.

I remember he showed up at the magazine in his zombie state, when he was falling apart. He walked past me to talk to Trish at her desk. Then, on his way out, he stopped by my desk. I was busy with the test article for a Young Adult editing job. It had to be in the mail that day, and I was getting the last details together. So I didn’t look up. Walt said my name, repeated it, and I saw no reason to break concentration. After a minute he slunk out of the place. I never saw him again.

About a dozen years later I was working freelance at a trade paper’s copy desk. In between stories I read the Times on the Net. There I found the obituary of Walt’s father, the old Times emeritus figure. He had just died, and the obituary was from that morning. The tail end told what was going on with the children. Walt’s younger brother was married in Connecticut with two kids and a wife and had been elected to something pretty decent in county government. Walt, unmarried, lived up in Canada. The article said he was a freelance copy editor living in a place called Gladstone, Ontario, or something like that. It was a town near Toronto, and it had an august place name taken from England.

I Googled Walt’s name and the name of the town. A review from, let us say, the Gladstone, Ontario, Tribune-Messenger came up. It was of a performance at the town’s high school, one given by a local amateur jazz combo that had performed very well. I read the following, or something like it: “Walter Friedlowe, the band’s clarinetist, contributed a sensitively crafted, musically alive solo of tender feeling.”

That’s what I was left of my old enemy. He wasn’t going to be managing editor of The New York Times, nor a magazine feature editor, nor a science fiction writer. At age 45 or 46 he would live in suburban Ontario and edit whatever copy people sent him. But when he played the clarinet for a high school auditorium, he would play it like he meant it and the audience would be glad to hear him. So is this a happy ending or a sad ending? I still don't know.