Part 1: How to Improve Your Memory

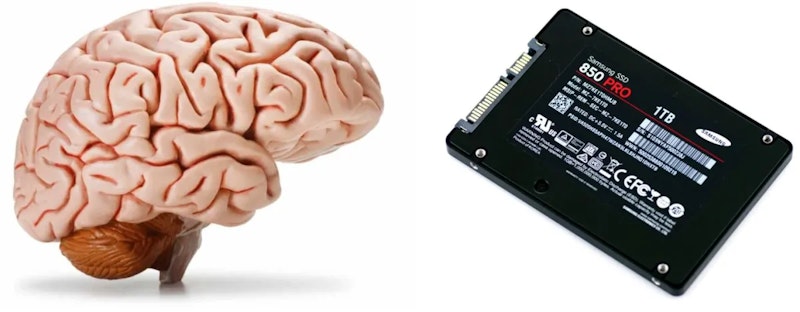

Most people consider themselves to be smarter than computers, which is accurate: they are. So why are computers, by all appearances, so much better than human beings at storing information?

Moreover, if computers run out of hard drive space, won’t we experience the same limitations ourselves if we start trying to remember everything? Isn’t it, really, the jingle from that Doublemint commercial (“Double, double, your enjoyment… Double it, double it, come on and double it! With Doublemint, Doublemint gum!”) that’s keeping me from learning all the names of my newest students? I’ve conducted many informal interviews, and I’ve learned three indisputable facts:

—People usually blame viral television commercials, pop songs by women, and their high school history courses for the difficulty they have remembering important things; this, however, is a mistake.

—Somehow, both home computer alerts and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle are partially responsible for our commonest misconceptions about memory.

—Most models of consolidated (long-term) memories, even the ones neuroscientists use, are so simplistic that they do more harm than good.

Let’s consider Doyle’s famous, fictional detective, Mr. Sherlock Holmes. He was a genius; he ought to have lots to say about memory. We first get to know Holmes through Dr. John Watson, a friend and sidekick who undertakes (early in their acquaintance) a study of everything Sherlock knows. Watson’s disappointed by the resultant chart; Holmes doesn’t know many things that “any civilized being” ought to have ready at hand. Watson tells us his surprise “reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the Solar System. That… appeared to be to me such an extraordinary fact that I could hardly realize it” (from Chapter 2 of A Study in Scarlet).

Watson tells Holmes about the Earth and the sun, and which one revolves around the other. “Now that I do know it,” Holmes retorts, “I shall do my best to forget it.”

“You see,” he explained, “I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things, so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skillful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.” (A Study in Scarlet, from Chapter 2).

Holmes’ exasperated, arrogant posturing to Watson—especially once he casts himself, with fake humility, as “the skillful workman”—is as charming and lively as ever. Nearly 150 years after Sherlock’s debut, however, we can be completely certain that his theories about memory were wrong.

It’s not all that rare for a scientific theory from 1887 to have become, in 2024, little more than a quaint error, but it is rare for most of the educated population not to notice. Thanks to our computers, with their (almost) perfectly flat, magnetic hard drives, we still worry about “running out of memory,” just like Holmes did. The etiology of dementia, which usually strikes during later adulthood, also suggests (irrationally) that memories overwhelm us when we acquire too many of them.

The latter assumption, related to dementia, is a simple error of attribution. Age-related changes to our neurons, and to other biological systems (e.g. our blood vessels), produce most late-onset dementias. They’re not caused by memory overload.

The difference between a hard drive and a human brain, however, is more subtle. Holmes is wrong about the topology of human memory. Memory doesn’t exist as a series of compartments, shelves, or rooms, where the past gets piled or sorted. (In this regard the mostly excellent film Inside Out does us a disservice by depicting memories as bowling balls.) In a human brain, memories are networked, on the basis of associations that connect all kinds of disparate things. Some of these associations are rational—two related legal cases, for instance, that gradually become inseparable in a lawyer’s mind. Some have a certain emotional logic, like a sad song you always turn on after receiving sad news. Some are purely circumstantial: remembering where you were on 9/11, for example. All three types of remembering apply to every memory we have; also, the more we call upon a certain memory, for any reason, the more vivid and accessible it grows. In fact, the diffuse, networked quality of memories, which allows them to be “stored” and “tagged” in overlapping ways within the brain, means that remembering—including remembering something long past, or imperfectly perceived—should get easier (on the whole) as you continue learning new things and having new experiences. The holographic nature of information stored in the brain—which is a fancy way of saying that specific memories are stored via multiple, simultaneous arrangements of different, linked neurons—enables our memories to “share” the neural links that constitute them. This happens so efficiently that there is, theoretically, no limit to the final amount of “stuff” someone can accurately remember, if they do one simple thing: connect whatever they’ve recently learned to other things they remember or know.

Creating such links requires three different types of thinking—analogical reasoning, active imagination, and moral concern. Joshua Foer has the imagination part down. Here’s how his tour of our memories begins:

Dom DeLuise, celebrity fat man (and five of clubs), has been implicated in the following unseemly acts in my mind’s eye: He has hocked a fat globule of spittle (nine of clubs) on Albert Einstein’s thick white mane (three of diamonds) and delivered a devastating karate kick (five of spades) to the groin of Pope Benedict XVI (six of diamonds). Michael Jackson (king of hearts) has engaged in behavior bizarre even for him. He has defecated (two of clubs) on a salmon burger (king of clubs) and captured his flatulence (queen of clubs) in a balloon (six of spades). Rhea Perlman, diminutive Cheers bartendress (and queen of spades), has been caught cavorting with the seven-foot-seven Sudanese basketball star Manute Bol (seven of clubs) in a highly explicit (and in this case, anatomically improbable) two-digit act of congress (three of clubs).

You can see him drawing on the analogical nature of memory, as well as his imagination, in order to create this rumpus. Analogies are just linkages: by putting Rhea Perlman in a compromising position with Manute Bol, he’s linked and sequenced them, albeit irrationally. The brain doesn’t place a premium on strongly logical associations; it holds onto associations that are vividly experienced. Judging by that criterion, the imaginary escapades of Rhea and Manute will do fine. In fact, even if you take the cards away, Rhea and Manute will be connected in Foer’s mind, and not merely because he’s imagined them having sex. Look at his paragraph again. Do you see it? They’ll be linked by their great difference in height. Perlman is a very short woman, and Bol is a very tall man.

This is where it gets interesting, and here Foer falls short. He gives us the facts about a very interesting case of prodigal memory, which he entitles “The Man Who Remembered Too Much.” But he doesn’t realize what the life story of that tragic individual could mean for the rest of us. More about that in our next installment. “How to Improve Your Memory,” Part 3.