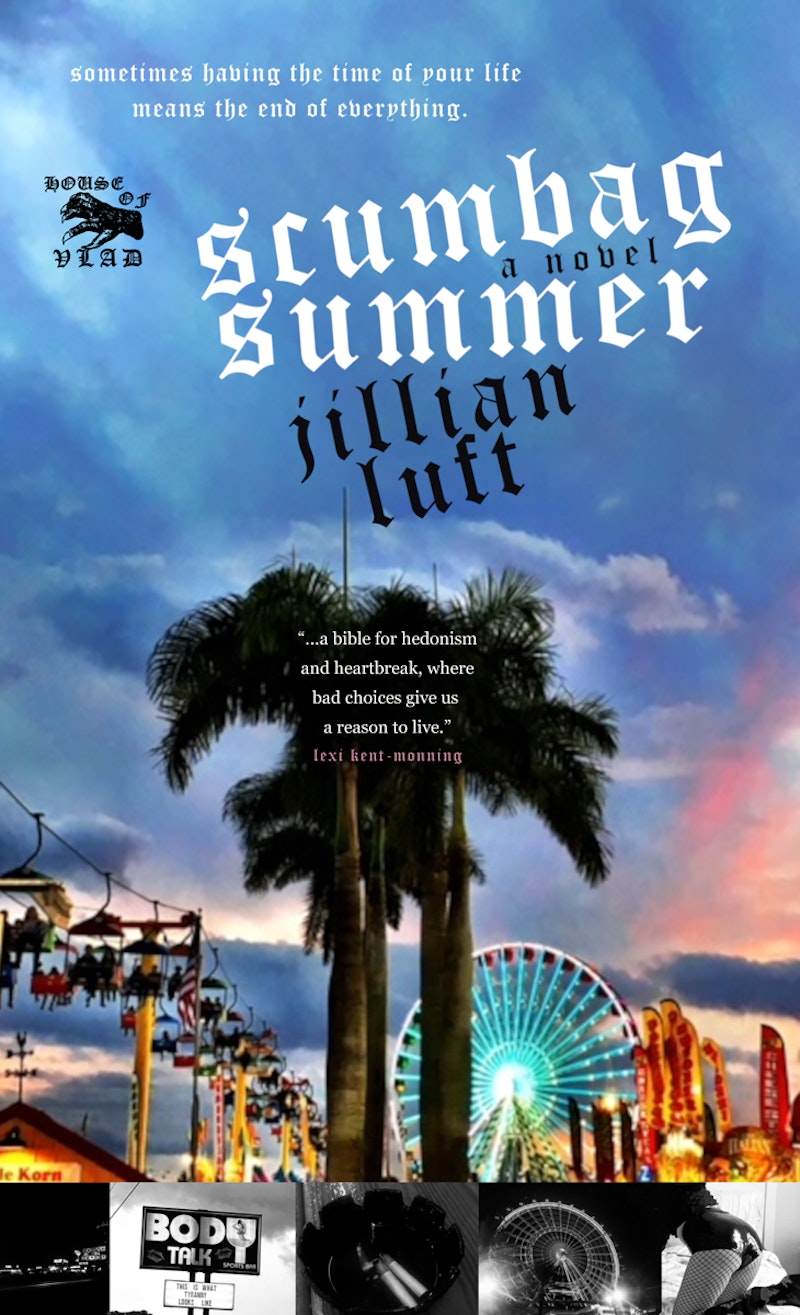

While major book publishers inundate consumers with pastel-covered chick-lit upper-middle-class “hot girl summer” reading this season, indie publisher House of Vlad Books and novelist Jillian Luft offer readers her novel scumbag summer as the working-class middle finger reply.

scumbag summer is a (mostly) first-person journey into a young woman’s summer in Orlando, Florida. The nameless narrator comes from what she calls a lower-middle class family—parents divorced, her father too much of an odd duck for her to have any relationship, though she at least maybe still talks to him. The narrator’s mother died when she was 13 and barely gets a mention until later in the story. The creepy stepfather does what creepy stepfathers do. The narrator has never learned to love, or be loved. Despite this background, she gets through college and scumbag summer takes place in the summer right after graduation, when she moves to Orlando to stay with an old friend (who seems just as lost) for lack of anywhere else to be able to go.

All of this is revealed in scattered paragraphs and lines of dialogue. The narrator, and Luft, are more concerned with the present, and don’t rely on long chapters of flashbacks into childhood to explain motivations. More important to the narrator is figuring what she’s going to do with her life, because she feels she can’t break out of her lower-middle-class background and re-define herself. Though there are inklings: with an encyclopedic knowledge of rock music, she writes and publishes her first music review in the local paper.

While a traditional “coming of age” story usually happens to a teen, scumbag summer deals with how, or if, the narrator comes into full adulthood. She’s not a dope like Jason, the Jacksonville Floridian from the tv show The Good Place, though she’d get along great with him—and be friends with the other lower-class character, Eleanor. scumbag summer’s narrator has a certain confidence, and/or at least takes responsibility for her decisions, especially with sex, even as she knows those decisions may not be wise. But, she’s trying to enjoy herself, even if/as she settles for menial office-drudge job.

The big shift in scumbag summer is when she becomes involved with her boss, an older married man. There are so many ways this set-up could go wrong, or not believable. The narrator’s human, the situation’s human, even if readers might know more than the narrator in this case. And she’s not an unreliable narrator—she never lies to us, only maybe to herself. Most important is she doesn’t feel like a victim. She’s enthusiastic about his attention. The interest of the story is to ask why—what’s her motivation? The strongest reason, at least the beginning, is that he’s the first person to:

….refer to me as a “woman.”....Most men remark upon my girly and adorable nature. Innocuous and unthreatening. How cute I am. “Cute” being diplomatic code for “pretty, but not gorgeous.” “Cute” intimating something’s off somewhere with the form or the face or usually both. And what’s off is that they don’t feel the need to bang me into oblivion.

He’s the first person to see her as an adult. At least that’s what she thinks. Whether that’s really true may be the determining factor as to whether scumbag summer will be a tragedy or romance. Every time he enters the story, and her life, the narration shifts to second person, “you,” or, him, the older man. That technique shows just how focused on—maybe probably obsessed with—she is with him. And as the story progresses, the novel can be seen as a second-person narrative: she’s telling him her whole story. Their whole story.

Equally important to the plot is Jillian Luft’s style: gritty and/but poetic. Some paragraphs—a lot of the book—read as prose poems. Not in a melodramatic way—Luft writes in basic American English, but she uses poetic techniques, like Anne Waldman’s “chant”—repeating a word or phrase to build energy, like in this excerpt from an early paragraph describing Orlando:

Orlando is straight trash. Orlando is a Day-Glo heap of recycled magic and wish fulfillment for lowbrow clowns, for impressionable suburbanites who believe that if you work hard enough, you’ll receive happiness for the low, low price of... Orlando is a sanitized Vegas with a seedier underbelly. Orlando is a carnival for the recently incarcerated. Orlando is where bad parents do penitence, maxing out their credit cards as recompense for the inherited demons they unleash on their spoiled children.

Luft writes similarly to poet and novelist Kim Addonizio—with both, their lines move fast and smooth, but also with power. And irreverence—neither Luft nor her narrator take themselves too seriously, even though there are some serious issues happening. And while this ironic distance the narrator takes offers humor, it also adds sadness—it’s a defense mechanism against her pain and anger. The narrator just doesn’t have a good adult role model to talk to. Thus, the attractive older married man.

scumbag summer seems at first to imply that it’s the narrator’s summer of getting involved with the scumbag men of Orlando. But there’s a sense that all the men in that working-class world (like some of her co-workers) are scumbags in that they’re just gruff, maybe vulgar, not polite company, but perhaps funny and fun to smoke a joint with. Scumbag as ironic self-descriptor. The narrator feels comfortable with people like that, they’re who she grew up around, so—though she doesn’t say it—she identifies as a scumbag in her own right.

The appeal of the novel, and the narrator, is that we sense that she’s outgrown that world—she doesn’t advertise herself as a college grad, but she is, and she’s more book-smart than everyone around her. She’s funny and clever, and that sets up readers to root for her. This one summer of scumbag summer feels like the “make or break” for her—either she stays an office drudge and marries a scumbag, or figures out that she has more and better options, like doing something more creative with her life.