Detective stories thrive on MacGuffins, but in the new Thomas Pynchon novel Inherent Vice, the entire detective-story frame is a red herring. Ignore the promise of genre stylings; this is a full-bore submersion into paranoid Pynchonalia, replete with sex, drugs, junk culture, made-up songs, and goofball names, all deployed with Boschian excess and the same combination of humor and millenarianism that animated Gravity’s Rainbow. Nearly all of Pynchon’s books, including this one, set in 1970 Los Angeles, are historical fiction, and they cartwheel through time and space without regard for linearity. But they’re all inextricably of a piece; this writer is as much a creator of alternate worlds as any sci-fi or fantasy novelist, and Inherent Vice, if nothing else, is a welcome opportunity to spend 370 more pages in his brilliantly written bizarro universe.

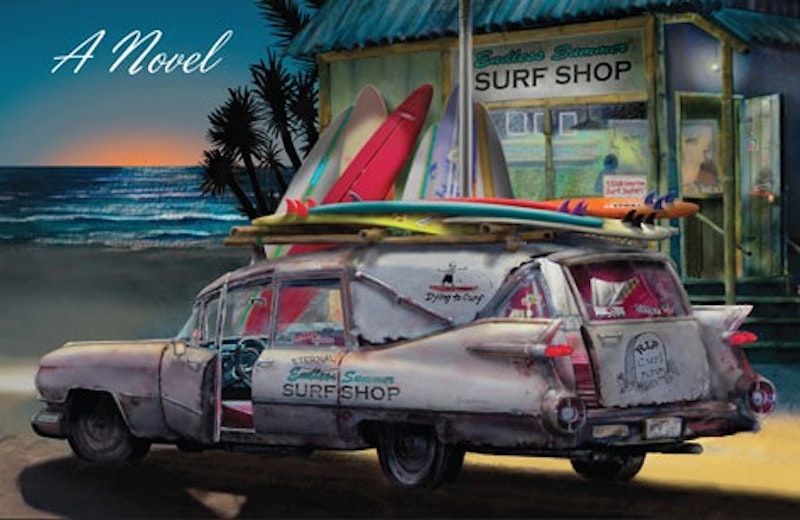

A reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, often earned, has followed Pynchon since the criss-cross plotting of his debut, V. (1963), still his most perfect novel. Inherent Vice is nearly the breath of fresh air that it promises to be—there’s a clear protagonist, the Afro’d pothead gumshoe Doc Sportello, and an unfailingly linear plot with a straightforward mystery at its center: Sportello’s looking for the disappeared developer Mickey Wolfmann, the philandering boyfriend to Doc’s own former lover, Shasta Fay Hepworth. Wolfmann’s gone missing, and as both noir and Pynchon conventions dictate, the initial search for clues soon gives way to a giant conspiracy with a shadowy entity, The Golden Fang, at its center.

The Golden Fang is another of those all-powerful, global-reaching corporation-cults that pop up in Pynchon’s fiction, like W.A.S.T.E. from The Crying of Lot 49. They seem to have control over everyone’s actions, but no one knows who they are or what they do. All that matters is Pynchon’s insistence that they exist, and it’s his routine, continued disgust at these all-encompassing authority figures that gives his work its limitless punk spirit and anarchic creativity. “Difficult” though he may be, not enough people have defended Pynchon’s writing on the basis of how marvelously fun it is to read. Inherent Vice has less outrageous flights of surrealist fancy than his longer books—no trip down the toilet with Malcolm X on your trail, no tall tales of man-consuming cheese wheels rampaging through the countryside—but the imaginative reach on display is still dizzying. There are the names—Bigfoot Bjornsen, Fritz Drybeam, Sauncho Smilax—and the songs, as always, evidence of Pynchon’s ongoing efforts to stretch his fiction beyond the boundaries of prose and into film, music, and cartoons. There are the sudden, solemn moments of personal remembrance, in which Sportello recalls a beautiful moment with Shasta or his parents, which belie the common complaint that Pynchon doesn’t write complex enough characterizations. And there are of course the endless little inventions—custom-made pornographic ties, a proto-Internet called ARPAnet, a hotel called Toobfreex! where people come to watch any television program they want—that give Pynchonland its simultaneously sleazy and invigorating feel. All his books are populated with hucksters and con artists and ubiquitous masters of disguise (here it’s Coy Harlingen, a surf-rock saxophonist who gave up his family to spy for the feds), but they’re controlled by a master of the English language, particularly its American iteration, and we’re thus always happy, or at least grateful, to meet their acquaintance.

Inherent Vice lags in the middle, as is customary, though it’s perhaps a boon to new readers that there’s a middle at all, rather than an endless literary vaudeville production with hundreds of characters engaged in seemingly pointless set pieces. Doc is a fine private eye, though one with a prodigious marijuana appetite that understandably gets in the way of his snooping. And he’s not the only one drifting through the novel in a Pigpen-like haze of pot smoke; Inherent Vice revels in the stoner humor and culture that have always informed Pynchon’s work (when the title characters of Mason & Dixon meet George Washington, he tries hard to push an unidentified herb their way), making it perhaps the most proudly High Times-worthy novel ever written by a serious novelist. No doubt some will read this as an unfortunate development, perhaps the dumbing-down of this famously encyclopedic novelist, though that judgment misinterprets the heretofore standard balance of high (pardon the pun) and low cultures in Pynchon’s books. He’s always been a serious pop- and schlock-minded nerd with significant science and math interests in addition, it’s just that here he’s let those nerd impulses run free.

Which of course doesn’t answer the always-salient question: What exactly is Pynchon up to here? Shorn of the more intellectually provocative settings and theories of his higher-minded novels, Inherent Vice doesn’t seem to offer more than some id-expunging chapters where the author, his last two gigantic socio-historical novels having not garnered so much as a New York Times Book of the Year citation, upends “an unaccustomed genre,” as the jacket copy says. But that’s not quite right, and not only because, as I’ve said, all his books are mysteries of one kind or another.

Rather, the novel is an evocation of California’s culture of “illusory premises,” manifested simultaneously in the 1960s drug explosion and the state’s long history of capitalist exploitation. There’s a fine line, Pynchon claims, between the surfing, karma-obsessed dopers on Gordita Beach and the conniving businessmen who pave over paradise to make way for new-age resorts. It goes without saying that Pynchon’s sympathies lie with the counterculture, however ridiculous he may reveal the individuals to be, though Doc’s greatest friend throughout Inherent Vice (or at least the person he feels most ideologically attuned with) is the cocky Sgt. Bjornsen, a vehement opponent of hippie scum in all its iterations. Bjornsen’s just a man trying to do his job, and Doc comes to respect him despite all their superficial cat-and-mouse bickering:

“‘Bigfoot’s not my brother,’ Doc considered when he exhaled, ‘but he sure needs a keeper.’

‘It ain’t you, Doc.’

‘I know. Too bad, in a way.’”

Pynchon’s vision of society is one where gigantic corporations, always evil, vie with boisterous countercultural opposition for control of history, and his protagonists are almost always people who refuse pigeonholing in either camp. The flights taken by Pynchon’s lead characters is always away, no matter what that may mean—away from expectations, or the war, or imperialism, or even from other like-minded people, as evidenced by the Whole Sick Crew’s disgust for beatnik posturing at the jazz clubs in V. So Inherent Vice fits snugly into that tradition, where all traditions are suspect.

How perfect, then, that Pynchon even subtly subverts his most revered book, Gravity’s Rainbow, in Inherent Vice. There’s the made-up Gordita Beach, a kind of cross-coastal parallel to Manhattan Beach, where he wrote the earlier novel. Then there’s the L.A. police’s state-of-the-art facility, The Glass House, which sounds suspiciously like the Crystal Palace, the central metaphor for Western civilization’s hubris and vulnerability in GR. There’s also a minor character in Vice, a suspected villain with a swastika tattoo on his head, who turns out to be a barely threatening false lead; Pynchon seems to enjoy how the 60s counterculture has no equivalent to the very real Nazi threat that loomed over Europe in Gravity’s Rainbow, though they remain just as paranoid. In this book, when someone says that “everything is connected,” they’re laughed at for being stoned. And, if we’d like to follow our own Pynchon-enhanced sense of connectivity, it’s worth mentioning that Inherent Vice, as many critics have already noted, seems noticeably similar to The Big Lebowski, which has its own spiritual precedent in Robert Altman’s shaggy Marlowe yarn, The Long Goodbye, released in 1973, the year Gravity’s Rainbow was published.

Which is all to say that Inherent Vice, while perhaps minor Pynchon, is still Pynchon. It still resembles little else in our literature and feels like the work of a brilliant, laughing madman. He’s one of the few living writers who have produced a body of work vast enough to be studied for a lifetime, and even this relatively svelte yarn would clearly benefit from a second reading. We should be lucky to have more books like Inherent Vice before he goes.

Inherent Vice, by Thomas Pynchon. 370 pp., The Penguin Press, $27.95.