I read that with the rise of e-books and publishing on demand, texts rarely go out-of-print in the old-fashioned sense. That may be true. But they certainly become harder to find, more expensive, and less visually appealing. For instance, a number of years ago I purchased a copy of Henry Stephen Salt's autobiography, Seventy Years Among Savages, from Amazon.

It was a paperback, made up entirely of scanned pages from a much-earlier edition. The cover featured what appeared to be an unrelated stock photo of train tracks. This humble copy of an animal-rights activist's memoir—originally published in 1921—cost over $20. And so it is with many old books on non-human protection.

One is John Oswald's The Cry of Nature, Or An Appeal to Mercy and to Justice on Behalf of the Persecuted Animals. Oswald was a fascinating figure, who died fighting monarchist forces during the French Revolution. Somewhat ironically, the vegetarian radical had a bloodthirsty reputation. On her podcast, “Food for Thought,” Colleen Patrick-Goudreau celebrated Oswald's 1791 anti-speciesist text. "It's amazing how much ground he covers in this very short book," she said. "After a few pages where he talks about the many ways in which we changed our relationship with animals over the course of many centuries, he goes on to suggest that through religion, rites and rituals, we make the final severance... I hear Oswald essentially calling our desensitization, our lack of compassion for animals, our fall from grace."

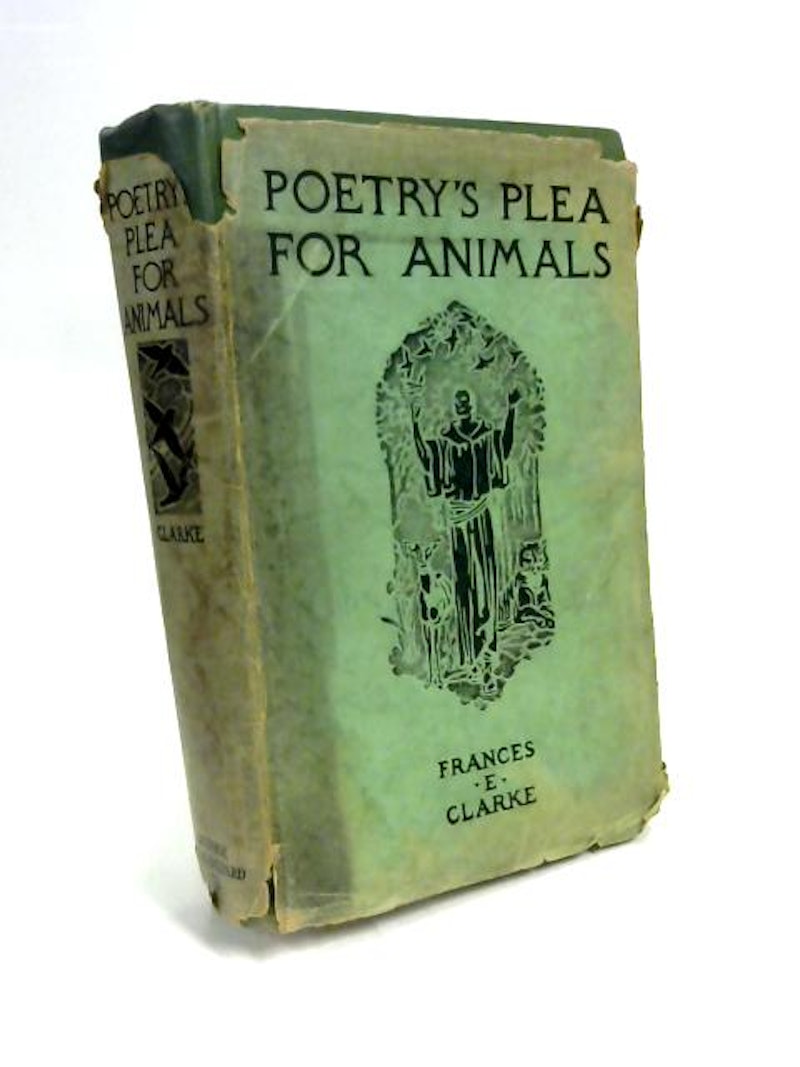

I'm also anxious to find an affordable copy of Poetry's Plea for Animals: An Anthology of Justice and Mercy for our Kindred in Fur and Feathers. Published in 1927, the title was edited by Frances E. Clarke. According to The Michigan Alumnus, Volume 54, Clarke was a teacher and one of the few honorary life members of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Patrick-Goudreau discussed Clarke's anthology on her podcast as well. "Written long before human innovators industrialized the animal-exploitation industries, these poems are a call for the liberation of animals," the podcaster said, noting she considered trying to republish the collection, which appears to be genuinely out of print. "The voices of these poems recognize the inherent cruelty and hypocrisy of a society where self-proclaimed 'superior' humans treated nature and nonhuman animals as our possessions."

Another book is Life of Frances Power Cobbe. It's an autobiography, which was originally published in two volumes in 1894. Cobbe founded the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection. Norm Phelps recounted the activist's life in The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA. "Although public sentiment against vivisection was slowly building in England and on the continent, no serious anti-vivisection movement would form until Frances Power Cobbe exploded onto the scene in 1863," the historian wrote, before mentioning her significant limitations. "[Cobbe] regarded vegetarianism as a violation of God's will. She was adamant that it must not be linked in the public mind with opposition to vivisection."

In addition, I'm on the lookout for a reasonably-priced copy of Ruth Harrison's Animal Machines: The New Factory Farming Industry. Published in 1964, the foreword’s by Rachel Carson. The now-largely-forgotten classic is often credited as introducing the problem of industrialized animal-agriculture to the public. Carol McKenna detailed Harrison's legacy for The Guardian. "Her descriptions of the new agricultural systems, including battery cages for hens, individual crates for veal calves and tether stalls for sows, in which animals were reduced to the status of production units, inspired Britain's first farm animal welfare legislation, the 1968 Agriculture (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act and also the European Convention for the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes, which was set up by the Council of Europe in 1976," McKenna wrote.

Finally, I’d like Henry Bailey Stevens' The Recovery of Culture, also seems out of print in the strict sense. I'm currently reading Vegetarian America: A History, in which authors Karen and Michael Iacobbo provide this description of the 1949 title: "[Stevens] explained that, like in the Biblical tale of Cain and Abel, the meat-eating keepers of the herds waged war upon the gardeners or orchard-keepers for more land for animals to graze upon. Thus, war came about only after human beings had slaughtered animals for their flesh."

This reminded me of one of my favorite animal-liberation books, An Unnatural Order: The Roots of Our Destruction of Nature. A quick Google search revealed that writer Jim Mason cited The Recovery of Culture in his text. I can't wait to trace the origin of this theory that really blew my mind when I first read it, less than a decade ago.

It will take some time to assemble all of these titles. Perhaps I'll get one for Christmas or my birthday. Maybe I'll receive one for Valentine's Day or Father's Day. But chances are that when I do add these five books to my shelf, I'll have a whole list of others to find. And while I want to read them soon, the slow process of collecting can also be fun.