The modern world wasn’t designed to coddle the poor. There's no accommodating the meek or fragile with empty pockets vs. wallets bulging with cash. The rich wouldn't waste their own spit on a thirsty beggar. The privileged share nothing, including bad advice and spare change. Those lucky few who make a mark leave behind tidbits of words with style, and a name to back them up. Poets like Whitman, Kerouac or Bukowski are far and few between. There are countless others who remain nameless yet the words ring true.

American poets are treated like some sideshow freak of nature. An elusive crazy bird that rarely shows its wings and confounds all who see it fly. Confused by the songs and sounds they create using words. Pitied and avoided for their calling. Pariahs of the dark carnival’s lost souls. In Europe the poet gets enough respect to keep pity at bay and some dignity to stay afloat. The poet never fits in anywhere.

One such poet was Jack Micheline, born Harvey Silver in 1929 in the Bronx. He came from Russian-Romanian peasant stock, as did most emigres during the great European migration to America. He chose the name Jack after Jack London and Micheline, his mother’s maiden name. Jack grew up in the streets and eventually was recognized as a street poet. An outsider who was shunned by academia and polite society. He reveled in upsetting the culture cart and loved pushing people the wrong way. He was a miscreant minstrel who liked to drink. He loved to carouse with loose women and hang out around the city in bars cavorting with criminals. He loved attending jazz clubs in Harlem. Making friends with Langston Hughes, Ornette Coleman and Charles Mingus. His poetry reflected the blues and improvised jazz he heard, putting his words to the down beat and time signature cadence of sound. A cacophony of street noise plus music and language, a double shot of poetry both foreign yet familiar.

During his early days in New York, Micheline saw his first book of poems, River Of Red Wine published by Troubadour Press in 1957.A forward by Jack Kerouac and complimentary Esquire magazine review from Dorothy Parker helped enhance his shaky career as a street poet and, to his chagrin, a reluctant Beat poet. By the 1960s Jack moved to San Francisco to join the counterculture movement of radicals in the new scene of artists, musicians, poets and weirdos who flocked to North Beach for free love, cheap drugs, psychedelic music and artistic freedom. Micheline was tired of the NYC Greenwich Village beatniks he viewed as phony stereotypes. Jack befriended Charles Bukowski, who was also just beginning his claim to poetic infamy in Los Angeles

In 1968 Micheline was hit with obscenity charges when publisher John Bryan printed his story “Skinny Dynamite” in Open City, the 1960s L.A. underground newspaper. The word “fuck” was included in the story. They beat the rap charge thanks to a civil liberties lawyer and now Micheline could add outlaw to his poetic license resume. But it was the publisher Bryan who was arrested, not Micheline or Bukowski. Jack was arrested too, but for pissing on a police car in North Beach. Jack was a brawler with a wise guy mentality. He loved to stir up trouble. Like his friend Bukowski he played the ponies. I discovered the work of Micheline in the early-1980s when I first read his book titled Skinny Dynamite after the original story that got him in hot water back in ‘68.

This collection of short stories was published by another SF poet legend (and good friend of Micheline), A.D. Winans. Winans is a respected elder and still an active poet today. Micheline had many supporters and detractors along the bumpy road. SF poets Bob Kaufman and Neeli Cherkovski were friends and like-minded contemporaries along with many Beat luminaries that grace the pages of various anthologies and biographies. In the early-90’s I began a regular monthly correspondence with Jack, sending letters to the Adobe Bookstore in the Mission District of SF. Jack was also an accomplished painter who was influenced and assisted by the abstract expressionist painter Franz Kline. There was reliable communication before cell phones and email. It was just slower and not as reliable.

Plans were made to bring Jack to the East Coast for readings in Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York. When he finally arrived at BWI airport I recognized him immediately. He looked like my drunk uncle wearing a slouch hat and a scarf like he just hit the trifecta at Pimlico racecourse. Jack was a little bit crazy, but in a good way. Things fell away from him and he wound up on my floor. He stayed in my attic for months writing, painting, arguing and screaming at the phantoms who tormented him.

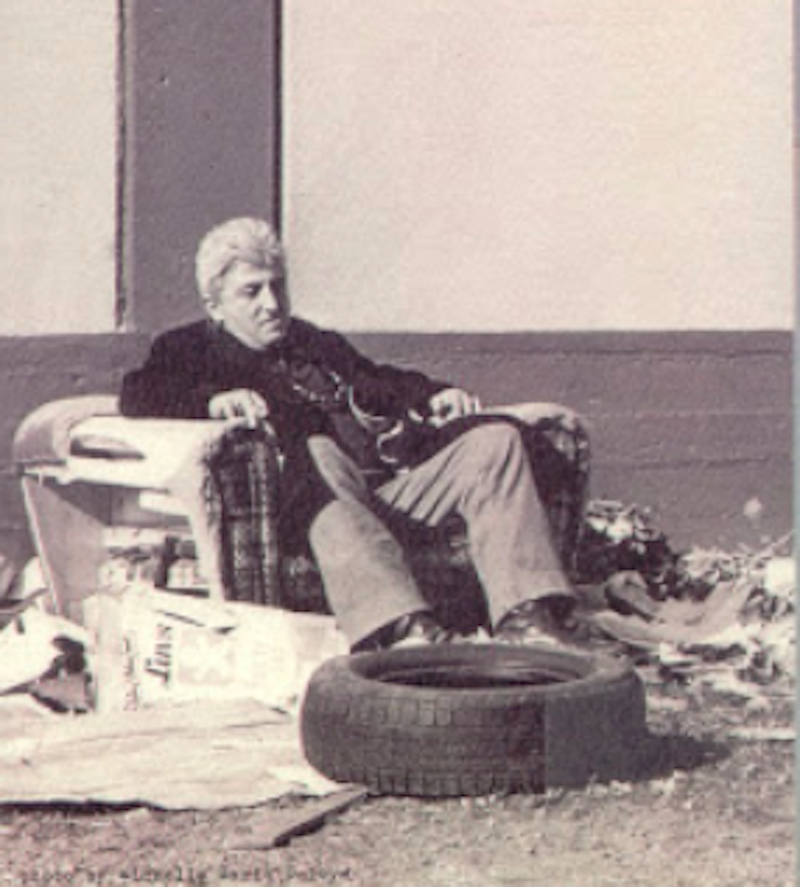

Jack was uncomplicated; he could be petty, vindictive, selfish, kind, supportive, funny and even happy. Yes, happy Jack, one of a kind like the title of a book of his poems the above back cover photo was borrowed from. An abandoned lot full of junk could be a living room too. Jack lived in the shadow of dreams, having imaginary conversations with his heroes, sinful saints, tarnished angels and holy devils that lived in his head. Singing a song nobody can hear but the world listens. “It’s the dead, it’s the dead, it’s the goddamn dead… it’s the dead who rule the world.”