(Second in Lovecraft series, the first one is here).

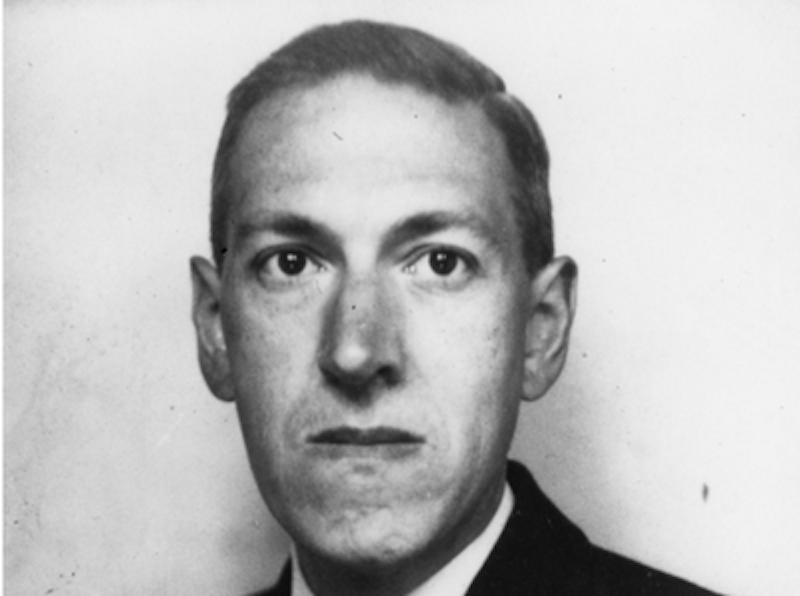

H.P. Lovecraft was a horse-faced, squeaky-voiced New Englander who never drank, dressed in threadbare clothing, employed absurdly affected spelling (“physick”), and who spoke in a stilted diction like a parody of a prissy old maid. His father died in a mental hospital, and later his mother did too, and Lovecraft spent the rest of his life living with an old aunt. When young, Lovecraft suffered from health crises that largely kept him out of school; then a nervous breakdown kept him out of college. Later he lived off sporadic ghost writing jobs and his inheritance, which was not large and eventually approached extinction. The neighbors thought he was odd, and a child from his neighborhood remembered how the adult Lovecraft would go skulking by, head down and shoulders low. He died in middle age, painfully and over the course of months, the victim of intestinal cancer. Now and then he wrote odd stories about the supernatural. Over the past 80 years or so these have become some of the best-known horror stories ever written.

The above facts are taken from H.P. Lovecraft: A Biography by L. Sprague De Camp, who also examines Lovecraft’s bigotry and his aversion toward sex. (Lovecraft once excused himself and left a restaurant so he wouldn’t have to see his companions eat clams. He told them he had a fear of the sea, but actually he enjoyed the few times he sailed on the ocean. I know what I make of this.) Some fans of the supernatural have voiced their resentment of how De Camp presents a hero of the genre; one complains of the “weary contempt” that De Camp allegedly displays. I’d describe De Camp’s attitude as one of bemused impatience. De Camp was a disciplined and successful freelance writer, and his book often dwells on how Lovecraft ought to have conducted his career. Toward the end there’s a brisk summary of everything Lovecraft should’ve done differently, with learning shorthand high on the list.

When I was a boy and read De Camp’s book, this business of Lovecraft the bumbler seemed to me like its overwhelming theme. Reading the book again, I find the theme still present but not as lonely in its splendor. For example, De Camp praises Lovecraft’s great intelligence and the bravery he showed during a prolonged and miserable death. De Camp also records the consensus of the people who knew Lovecraft, a consensus that’s tricky to acknowledge in the case of a bigot. To read what Lovecraft had to say in his letters (De Camp provides quotations), he was a learned ass about race theory and spewed venom about Jews and blacks. But to know him was to know a man who always did the right thing by others (as opposed to believing the right things about groups). Toward the end of his life, his anti-Semitism ebbed away and his racism at least lost its serrated nastiness. But all along he was somebody whom numerous people were glad to know. There are many paragons of racial right-thinking who don’t fall in that category.

Of course, it’s a surprise that Lovecraft knew anybody. The oddball recluse began adult life hunkered at home, dreading the outside world. He never did get in step when it came to having a job and earning money. But, as the phrase goes, he found friends and a life. This wasn’t easy. One of his first and most famous stories is “The Outsider,” about a man who grows up much as Lovecraft did, except possibly worse: “Unhappy is he to whom the memories of childhood bring only fear and sadness. Wretched is he who looks back upon lone hours in vast and dismal chambers with brown hangings and maddening rows of antique books,” etc. The hermit is trapped in an edifice somewhere, apparently off in limbo. He grows up knowing the world only through books, and recalls how he’d “longingly picture myself amidst gay crowds in the sunny world beyond the endless forests.”

He makes an attempt to break free, an attempt that fails: “As I went farther from the castle the shade grew denser and the air more filled with brooding fear; so that I ran frantically back lest I lose my way in a labyrinth of nighted silence.” But he tries again, and after many adjectives he arrives at another castle, this one populated: “What I observed with chief interest and delight were the open windows—gorgeously ablaze with light and sending forth sound of the gayest revelry. Advancing to one of these I looked in and saw an oddly dressed company indeed; making merry, and speaking brightly to one another. I had never, seemingly, heard human speech before and could guess only vaguely what was said.”

He breaks in upon the people, but with bad results: “Scarcely had I crossed the sill when there descended upon the whole company a sudden and unheralded fear of hideous intensity, distorting every face and evoking the most horrible screams from nearly every throat.” They run and he’s alone again. But why? He sees a creature staring at him and it’s a fright, “a leering, abhorrent travesty on the human shape.” As you may have guessed, a mirror is involved here.

Lovecraft wrote this story as he was turning 30. It was in this frame of mind that he’d begun to ease his way into human company—meaning the company of humans other than his relatives—after the years he spent recovering from his college fiasco. You can see how such company might indeed have rejected him, given the description in this piece’s opening paragraph. You can also see how he might never have tried, or how he might’ve tried and given up. But he wanted to live, and like most of us he felt that meant being a person among people. His route toward that status was difficult and perhaps painful. For instance, I remember an account a friend of his wrote about sitting with Lovecraft in an ice cream parlor and hearing people at other tables snicker as his high voice discoursed away about the flavors he liked. The friend reflected on why people have to be mean about someone just because the person’s different. I had occasion to reflect on that sort of thing when I was a kid, and so have many others. Apparently, Lovecraft found himself in such situations as an adult.

Yet he managed. He found people who cared about him, and he gave them good reason to care. No, marriage didn’t work out for him, but his ex-wife remembered Lovecraft as one of the kindest and finest people she’d ever known. Not much worked out for him, really. His life was shorn of so many things. A sense of accomplishment, for one (“the world’s most perfect cipher,” he described himself toward the end). And acknowledgement from the world for his writing (letters to Weird Tales, a pulp magazine, were about as much praise as he got). The self-respect that comes from supporting yourself, the peace of mind that comes from tackling your problems and sorting them out, the confidence that you can step out the door and find yourself at home in the broad world of others—he never had these either. He never found lasting love, and sex was a blight to him, not a pleasure. No wonder he gave vent to the nastiness of racism, and the hysterical strangeness of the stories his fans love. But his spavined life, his crippled life, was a long way from being a simple surrender.

The written word made that resistance possible. There were many people Lovecraft couldn’t mix with, but he could mix with fandom: that new breed hatched by the pulp magazines and fostered by the U.S. mails, people odd enough to spend their passion on debating and admiring adventure stories, horror stories, science fiction stories and fantasy stories. Letters back and forth to these people eased Lovecraft out of his post-college isolation. By the time he could face others, these were the others he faced. They made up the backbone of his social life forever after.

But he built from there. One of Lovecraft’s fellow pulp writers, a more two-fisted sort, gave De Camp a charming account of the visit the mature Lovecraft once paid him. The host and his buddies knocked back beers; Lovecraft held forth, squeaky-voiced and ornately articulate as ever. The buddies—apparently not fandom types—thought he was swell. The Lovecraft who climbed out of his former isolation was a man who delighted in a visit down South where he saw alligators and did physical work in the sun. He took an economy-class train ride up to Québèc City and admired the Québècois fellow passengers packed about him (“tough little frog-eaters”). He still spent most of his time at home, but it was time devoted to connecting with others, not cutting himself off. De Camp estimates that Lovecraft’s letters add up to 10 million words, and his correspondents and subjects ranged far beyond fandom. The man who began life hidden away finished with a vocation for explaining himself to others and listening to what they told him back.

Then he died. He’s remembered for his stories, which were the product of a malformed psyche and distorted life. He’s sometimes reviled for his bigotry, which I think sprang from the same sources. But he fought a long way toward wholeness. He wanted to live, even if he was never that good at it. That’s what I’ll remember him for.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3