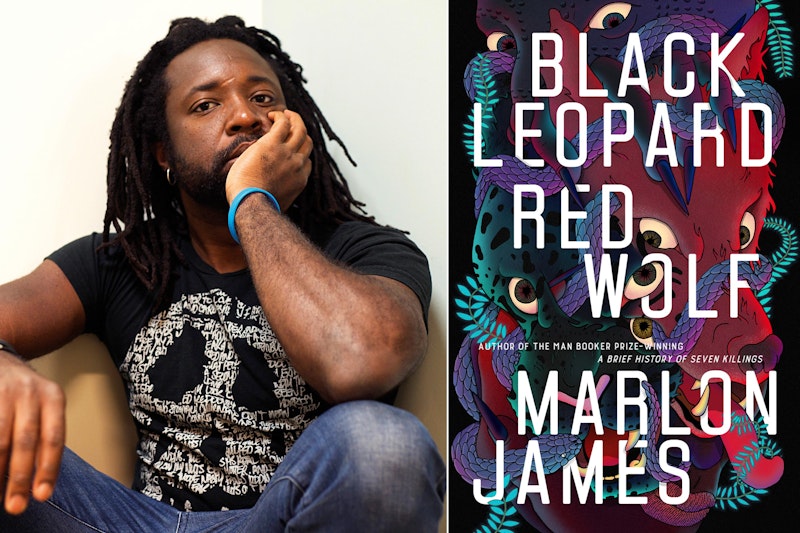

It’s very difficult for a famous person to be lighthearted without being misunderstood. After Marlon James won the Booker Prize for his 2014 novel A Brief History of Seven Killings, he tried to make a joke about his next book, and said tongue-in-cheek he was writing “an African Game of Thrones.” To his dismay, people took the line seriously. Including the marketing department at his publisher.

Black Leopard, Red Wolfis now out and you can see why the tag stuck, however much James thought he was kidding. It’s a 620-page novel that takes place in a fantasyland filled with magic, monsters, bickering royalty and African cultural markers (like griots, West African bards, and sangomas, Zulu spirit-healers). There’s a lot of sex and violence and sexual violence. But it has a very different attitude to story than Martin’s fantasy epic. It’s a stunningly well-written book, but that sense of story makes it difficult in a way that might defeat a lot of readers.

The novel follows a man named Tracker, a bounty hunter and retriever of lost people, who’s hired to recover a kidnapped child. Inevitably the child’s more than he seemed, and it’s unsurprising that Tracker’s accompanied on his quest by a variety of strange and powerful colleagues. But the structure’s odd. The first-person narrative’s framed as Tracker’s “confession” to an inquisitor some time after the main events of the book, yet the quest for the missing boy doesn’t start for over 100 pages. And the boy’s never more than a job to Tracker, who’s profoundly uninterested in the aristocratic machinations around the child.

There’s a sense in which the novel’s not really a quest tale but a story of Tracker’s loves and betrayals. Gender plays into the story on a number of levels, from the magical significance of circumcision early on to the dynastic quarrel underlying the quest for the boy, but Tracker as a gay man feels at an odd remove from all that. There’s a lack of complication his love. A black were-leopard with no name beyond Leopard is his first lover; there are others. After the story jumps forward in time a few years we meet a man who betrayed Tracker to were-hyenas, which results in Tracker getting a wolf’s eye implanted in his head in place of his own: thus Black Leopard, Red Wolf.

Tracker doesn’t present his tale as a love story, though, or as a bildungsroman. The book’s difficult to parse as a result, especially while reading through the early parts of it. Dramatic tension never emerges. Intensely readable on the level of the sentence and paragraph, it’s hard to find a reason to care over the course of hundreds of pages.

It helps, at least in terms of clarity, that characters tell and re-tell other characters the story. The re-tellings don’t give you much of a clue what to read for, though; how to find the drama in your own head. Some of Tracker’s reflections suggest that as far as he’s concerned a story’s an artificial and dishonest structure when overlaid on actual events. A story’s an abstraction of reality, not a movement closer to it.

The book as a whole tends to support this approach. It reads as though James is disillusioned with narrative, even writing against it. This isn’t a fantasy epic, then, but an anti-epic, an un-telling of story. James has said that the next two books in the series (to be known as the Dark Star trilogy) will re-tell events from the perspective of other characters, Rashomon-like. There’s certainly enough matter here to justify that approach.

The book’s prose is excellent, thoughtful and terse, even jagged. Notably, James avoids giving any easy catharsis in his fight scenes, which proceed at unexpected paces, brief or extended. Set-pieces with rising and falling action are uncommon. There’s little power fantasy here, only hurt and pain and frequently defeat and loss.

Nor do we get the usual fantasy-novel pleasure of learning the intricate details of a world in depth. We get just what we need to know, and only when we need to know it. Tracker’s not much interested in politics, history, or culture, except when it matters directly to him. By the end of the book we have a grasp of what’s going on in this continent, but it’s knowledge that emerges bit by bit, as though Tracker’s a child growing into an understanding of his everyday world.

And yet Tracker himself resists growing. He’s bitter, often misogynistic, and not as clever as he thinks. He lives in a mythic world filled with magic and monsters, but isn’t impressed by any of it. Much like the story overall, he’s precisely imagined but difficult to like. Oddly, his strong sense of smell—“it is said you have a nose,” other characters muse again and again—is weirdly inconsistent. He can smell the kidnapped child at great distances, giving him a plot justification for being pulled into the quest, but frequently misses scents of things and people closer by that he perhaps should’ve picked up.

It’s an odd flaw in an otherwise very well-written book, the kind of flaw I think would drive a lot of Game of Thronesreaders nuts: a failing (deliberate or not, it must be a failing) that works against the basic logic of the book and what we’re supposed to know about the character. In the end, Game of Thronescomparisons are misleading for reasons of exactly that sort. The audience for Martin’s books will not, on the whole, be pleased with what this book does. It’s far more thoroughgoing in its rejection of heroism and its skepticism of grand values, extending to skepticism about storytelling itself. It’s easy to admire this book. But I suspect a mass audience will find it a challenge to extract pleasure out of it.