Readers know the story of a mind unraveling. The written word's emulation of a logical brain gone paranoid from guilt and succumbing to madness has been used in horror dating back to Edgar Allan Poe. While the EC Comics of the 1950s might remain in the popular imagination as a collection of gruesome images—the covers that elicited Congressional hearings—their lasting legacy would be the heavy reliance on captions that tried to grab the glory of literary ambition by offering up typeset words to read. Probably the most widely-read American horror comic of the past 10 years' graphic novel boom, Charles Burns' Black Hole, carries the voice of teenager's thoughts so close to it that a reader accustomed to the comics medium can feel like the beautifully illustrated graphics that are the best reason to read the work are propped up on legs of nondescript prose. In Conor Stechschulte's The Amateurs, now re-released as a graphic novella from Fantagraphics Books, readers take in something comics can capture better than prose, the blankness of a mind already gone.

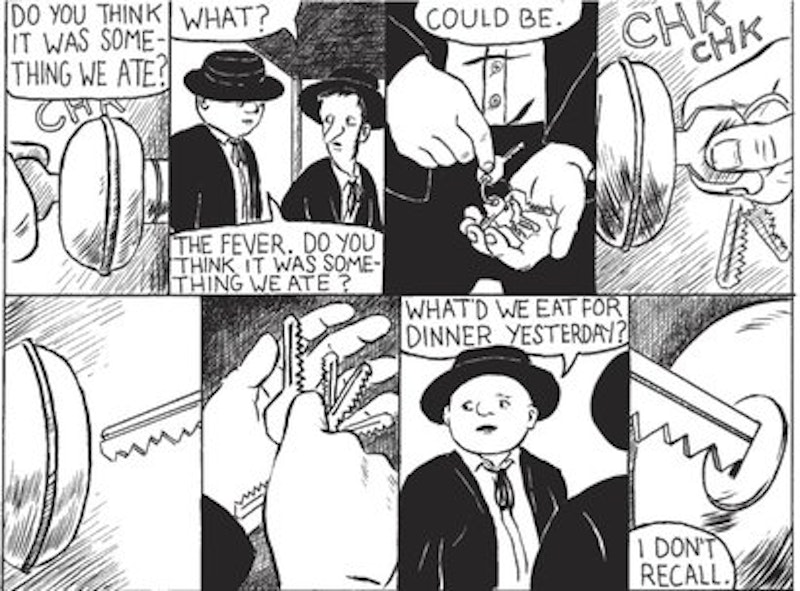

Two butchers, Jim and Winston, their bodies designed like comedic archetypes, one skinny and big-nosed, the other bald and rotund, go to work one day after being sick the night before, and find there is no meat in the display case and no memory of how to do their jobs. These lacunae in their consciousness seems vaguely attributable to some sort of supernatural interference, but this explanation, while it makes for an atmosphere of unease for the reader, is not for the characters to consider. In the present moment, the butchers need to get to work, selling meat they do not know how to prepare. There's a comedy of errors, as they struggle to work, but the brutality of the task they are assigned, the steps that need to be taken to get from a living cow to a pound of chuck beef, makes the humor register only at an oblique angle to what we witness. Jim and Winston wear deadpan expressions the best they can, but still end up covered in blood.

Inspired by a passage in Werner Herzog's Conquest Of The Useless, Stechschulte began work on The Amateurs while working as a security guard at the Baltimore Museum Of Art. This job afforded him plenty of time to undertake creative pursuits, such as writing song lyrics for his band Witch Hat. On days when the museum was closed and he had nothing to do but stand at the front entrance and inform visitors of this fact, he had the freedom to lay out a comic more long-form than anything he'd done before in his sketchbook. Citing the silent approach to action used by Fort Thunder artists as what got him interested in drawing comics, and the pleasure he takes in reading passages of later Cormac McCarthy that “just follow someone doing stuff,” his pages are dense with multiple images depicting action unfolding. However, while a work like Brian Chippendale's Maggots, drawn in ink over a Japanese book catalog and published at scale, has a first-take immediacy to its scribbly figures, Stechschulte's more traditional process, sketching out roughs at a small scale, penciling pages at 15 by 20 inches, and then inking them to be reduced down, got him used to what these more fleshed-out characters do physically. Still, there is a velocity to the way the comic reads. There are no gutters of negative space separating panels, and each drawing presses up against another, with no constancy of a grid to cling to. This gives the book's movement a breathless quality, where panels of tiny moments of door bells ringing read like clauses in a run-on sentence, escalating tension as things keep happening.

This approach to storytelling, eschewing large chunks of text that would allow for declarative statements of feeling, makes the vision of human nature in Stechschulte's work feel like it’s defined primarily by furtiveness and secrecy. In The Amateurs, Jim and Winston are hiding their incompetence; but in other stories, found in assorted anthologies published by his small press peers, there are secret societies in the woods, and violent accidents regretted so much they cannot be spoken of. Sexuality occurs voyeuristically, as something characters whose thoughts are unknown to us witness being done by other bodies they cannot understand. “I'm interested in people seeing something they think they want to see, but it's different than you thought it was, or more than you bargained for.” This sense of scale, that we can see things outside the scope of what we know, is crucial to the weird horror atmosphere that pervades most of Stechschulte's narratives.

On a weekend in early March, Stechschulte was at the Open Space Prints And Multiples Fair. Alongside cassette tapes of the second Witch Hat record, were accomplished watercolors priced at $10 each. Many of these paintings, in their subject matter of the nude or undressing body, carry the same voyeuristic current as his comics, but isolated into the individual moments of a fine art context function as something decorative to hang in one's home or office.

Also still available were copies of the original version of The Amateurs, self-published in an edition of 300. “I have a lot of them. And I'm about to have a lot more,” he said, although the two versions do differ slightly. The new version sees print at a smaller size than the original’s classic comic book dimensions; something very close, actually, to the dimensions of the layouts worked out in his sketchbook in 2011. New pages are added, bookending the beginning and end with the voice of a new character, a girl who finds body parts washed up along a riverbank. “I feel a little weird about it,” Stechschulte says, about the use of narration that relays information his images already convey.

With the comic he's currently working on, a “psychological thriller” with a “long sex scene” titled Generous Bosom, he intends to play with a disconnect between narration and visual storytelling. The accomplishment of The Amateurs, of sustaining a story across so many pages, will be built on in that work, whose individual installments will be about the same length, but add up to tell a story between 200 and 250 pages. That work is to be published by Breakdown Press, a small U.K. based publisher whose roster includes the British cartoonist Joe Kessler, who Stechschulte admires enough to have a print of hanging above his lightbox drawing table. He's drawing these pages in pencil, twice, at the same size, and the finished versions alternate in drawing style between fairly open, dialogue-heavy sequences and wordless images, dense with hatching, that look incredibly beautiful.

When I visited Stechschulte's studio, his computer was open to Tumblr, where he had just posted one of his watercolors that were for sale at the PMF. Tumblr, with its constant stream of images, could spur increased visual literacy in a way that might make for an audience more appreciative to the sort of comics he creates. Certainly, with the voyeurism it allows, and the vague horror it evokes, it's right there in his thematic wheelhouse. Still, very few of his posts blow up in the way it is theoretically possible for an image to in social media. As visually driven as his approach to storytelling is, you still need to read it, and maybe it still needs the space that only existing in the physical world with your thoughts can get you. That's how The Amateurs was conceived: In the on-your-feet work that required a physical presence, with playing on a smartphone forbade. Many of the comics that are popular on Tumblr are simplistic, announcing their feelings and intentions in a way Stechschulte's work, oscillating between humor and horror, never does. The Amateurs may be a book about the blank slate of characters without memory, but it still requires memory enough on the part of its audience to read it, and appreciate the atmosphere it creates.

-Follow Brian Nicholson on Twitter @ownyouryogurt.