I’ve no idea why Christmas Day of 1971 is such a blur. It was, unfortunately, the last holiday I spent with my father, who’d pass away the following June, split into pieces by a heart attack at the age of 55. I do remember the season surrounding Dec. 25 of that year: I was the only child still living at home, a 16-year-old 11th grader at Huntington High School on Long Island, and it was a remarkably carefree year. My parents were tuckered out after raising five boys, and, consequently, I came and went at will. No curfews or questions asked when I came home blitzed on mescaline, Schmidt’s beer or joint after joint of dirt Mexican weed. Weekday afternoons were spent downtown at Kropotkin Records, in Halesite listening to music with my lifelong friend Elena, or making a quick trip to my dealer Tommy, and then finding an alleyway off New York Ave. to toke up. (Two of us would be in Tommy’s room, and his mother might barge in, oblivious to the transaction, and offer cookies and milk. Still cracks me up.) Homework at night, maybe a babysitting job in the neighborhood, lots of yakking on the phone and several nights a week watching a re-run of a 50s sitcom with my mom and dad before they conked out.

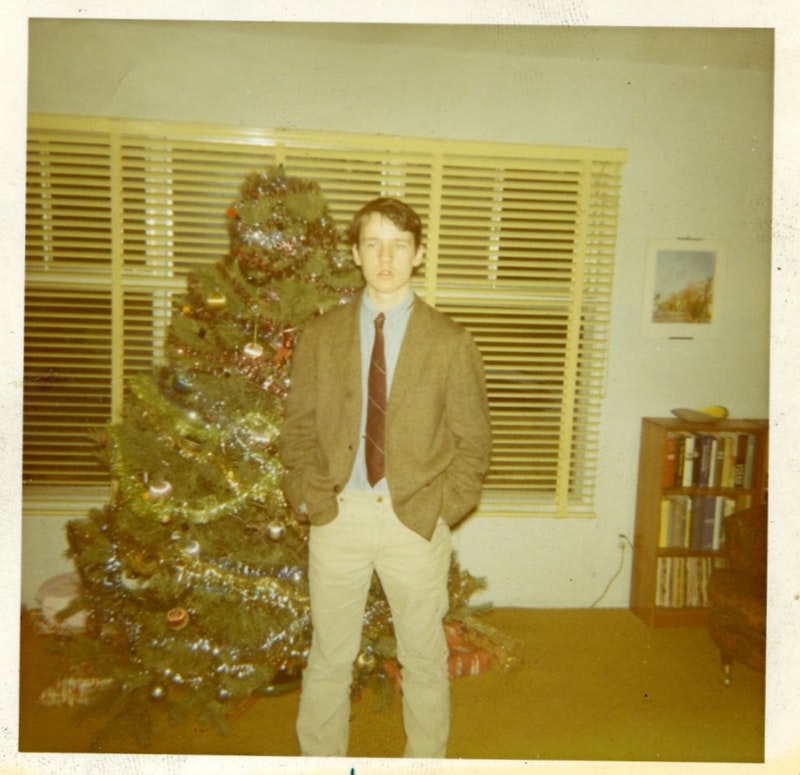

That’s not to say my parents were inattentive: college was coming up, but as I breezed through my classes, picking up all A’s with a minimum of effort, everything was kosher. I did get in trouble once that year, lassoed by the principal for obscenities in the underground paper The Crux that I wrote for, but my parents considered that small potatoes, not to mention an egregious violation of the First Amendment. In the picture above, I’d just come home from a Christmas party my elderly Latin teacher, Ernie Barra, had thrown, a small gathering for 10 or so, and my dad snapped the shot of me in front of our tree. The hair was short—shoulder-length locks were temporarily of out of fashion since the greasers and growing number of Jesus freaks at school had finally adopted that look—and I’m wearing a hand-me-down herringbone sports coat, a rumpled tie my mom bought for me a few years earlier at Chicago’s Marshall Field’s, a threadbare, light blue work shirt, Lee cords and construction boots. A dress-up variation of the cool kid’s uniform. It’s possible I had a copy of Dylan Thomas’ collection of stories Quite Early One Morning tucked in a back pocket; and I’m certain that the winter break had commenced.

As for Christmas Day that year it’s a blank, as I’m sure it is for my surviving brothers. One was off in Afghanistan with the Peace Corps; the two oldest had families of their own; and my fourth-oldest swooped in from his senior year at the University of New Hampshire. Don’t think it snowed that year, which at 16, was a blessing since it made driving easier, and I can’t remember if Dad continued his tradition of taking over the kitchen on Christmas morning, making pancakes and scrambled eggs. Probably not, since he’d suffered a first heart attack six months earlier and was on what passed, then, for a healthy diet.

Not much in the way of gifts—$25 in cash, fine by me—as compared to when I was a young boy, and would walk down the stairs at six a.m. and marvel at the spread my parents had laid out for their boys. The car wash my father owned didn’t spin off a lot of cash, and I was largely shielded from any money concerns, but man, they went all out for Christmas every year. Nothing outrageous, but there were plenty of toys, bags of caramels for each son, sporting equipment and the like. We all had specific landing spots, and as the “baby,” my gifts were under the tree. I hit the jackpot when I was 10, in 1965: not only a new baseball glove, but a sled as well, and as we had snow aplenty that year, after breakfast I gathered with neighborhood friends and we zoomed down our steep hill for a few hours, trying to dodge the cars that were stuck at the bottom, unable to make the treacherous climb from the night before. On one run I was going warp-speed fast, and since the sled steering mechanism wasn’t yet broken in, flew right under the station wagon of Don McGuire, lucky to escape harm. Luckier still to avoid the busy Southdown Rd. at the bottom of our LaRue Dr., an ever-present hazard that makes me shudder now, considering how many times I sledded right across the street, unable to stop, winding up in a safe snow bank.

It was the Smith’s turn in ’71 to host the family Christmas party; we alternated with my Uncles Joe and Pete, and everyone showed up. My cousin Steve, a year younger than me, was especially proud of an immense purple hickey he was showcasing by wearing a t-shirt; my niece Jenny, not yet three, mugged for the camera with a can of beer; cousin Bernadette posed with my parents’ three grandchildren, as well as her younger sister Ronnie; and my brother Gary—we exchanged records every year at that time—had a really cool V-neck sweater to go with his patched jeans. My older brothers were caught on camera speaking animatedly with Dad, undoubtedly about either the stock market or politics; and my mom was—in between bringing out platters of deviled eggs, bologna rolled with cream cheese and frozen Chun King egg rolls—hogging the gossipy conversation with my Aunts Winnie and Peggy.

Now, I can only relate this with the aid of old snapshots and memories of similar goings-on at Christmas. Nonetheless, fuzziness doesn’t obscure signature events of childhood, and if all the decades that have passed inevitably filter out some holiday-related unpleasantness—like when my dad and I strung up bright colored lights on the shingles of our modest split-level house, only to find just half of them worked after flipping the switch—it doesn’t matter much, for my childhood was mostly sort of magical, the last-born of a tight-knit family.

More recent Christmas Days are clear as a bell. In 1990, my wife Melissa and I were dining in Vienna’s Hotel Imperial, accompanied by a wealthy Texas widow whose stories as each course was served became more and more crazy. At first we were conned, but just as I getting mildly irritable with the chatterbox, I realized we were spending time with a lonely woman in her late-70s, and if she let her imagination run amok, what was wrong with that? Besides, had my Mom lived to that age, I doubt she’d have been much different.

On Christmas Day in 1975, I spent a few days at the home of my oldest brother in Short Hills, NJ, and I was in the doghouse with my lovely sister-in-law. My behavior in previous months at college in Baltimore—a split head after too much LSD and beer here, a concussion from dancing too fervidly and slipping on a marble floor there—were considered above the level of normal collegiate hijinks. Kathy was very generous on the gift front, but that year I received a large bath towel, with a card that read, “The equivalent of coal, Rusty. Your brother is worried about you, and that doesn’t make me happy.”

And of course my recollections of Christmases when the kids came along are in 20/20 vision: monstrous trees in our Tribeca loft, preceded by Christmas Eve parties—hey, the 90s rocked—and more presents than I can even countenance today. It was the thrill of seeing the two boys rip open the wrapping and going nutso, in Manhattan and later in Baltimore, that made time seem suspended as in an old Twilight Zone episode, but without any of the surreal twists at the end. No Art Carney, a fall-down rummy, morphing into a real Santa Claus, just happy moments etched in my mind.

Unless you’re a stinko grinch or flat-out misanthrope, it’s difficult not to favor a particular Christmas song, whether it’s a traditional carol like “O, Come All Ye Faithful,” the transcendent duet of Shane MacGowan and Kirsty MacColl singing the Pogues’ “Fairytale of New York,” or a tune I might consider a dog but warms your heart. As far as Christmas songs go, I make an exception of taste, and consider it a free game.

One song I play a lot at this time of year isn’t Christmas-related, per se, but it captures my approaching-60 state of mind. It’s the ’93 recording of “Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World” as performed by the late Israel Kamakawiwo’ole and featured in the underrated 2000 film Finding Forrester. When he sings, “Someday I’ll wish upon a star/Wake up where the clouds are far behind me/Where trouble melts like lemon drops/High above the chimney tops that’s where you’ll find me,” I might get a catch in my throat, thinking of all the family members that are no longer alive. But they’re the very best Ghosts of Christmas Past, and once the melancholia abates, I’ll chuckle at this or that holiday joke that long ago had me in stitches.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955