Since an early age, I’ve been overwhelmingly fascinated with city street maps, especially those of New York City. I would fill copybooks with lists of New York City streets, their beginnings and endings. I would pore over street directories published with red covers (hence their name, the Little Red Book) published by Geographia and other companies. My true allegiance, however, was to a company called Hagstrom, whose New York City maps were top notch for decades. The company was started by Swedish immigrant Andrew Hagstrom in 1916 as a drafting company that also enlarged photographs and images. The New York City map was produced almost as an afterthought at first, and it’s a tribute to how accurate surveying was, as well as rendering maps using only drawing and drafting tools, how terrific the Hagstrom New York City edition was when it first appeared in the early 1920s. The same base map was used for all subsequent editions until a CAD version supplanted it around 2000.

Though this same base map of Brooklyn Heights and the downtown area was used for decades, obviously, several changes needed to be made by hand over the years. The present-day Brooklyn-Queens Expressway that hugs the East River along Furman Street wasn’t built until the mid-1950s, and at the time Brooklyn still had a very active waterfront with numerous docks along Furman. There was a waterside railway, not yet shown in 1922, that shipped goods floated across the East River to area warehouses and factories.

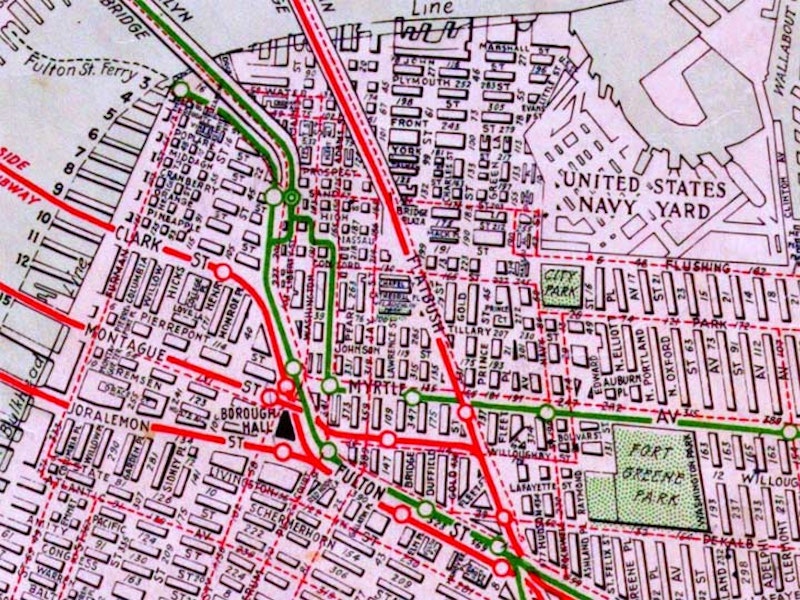

When Hagstrom maps were first produced, they were black and white with red and green added for subway (red) and elevated (green) routes. However, red lines occasionally showed elevated lines—those were subways that ran along elevated tracks for part of their routes. Green was reserved for strictly elevated lines. Hence, the Fulton Street El and Myrtle Avenue El, are shown as green. Much later, most of those els were torn down, with the remaining parts added as extensions to present lines: The A train along Liberty Avenue (Fulton Street El) and the M train along Myrtle Avenue to Middle Village (the M train). Years later, all Hagstrom maps were made with the 4-color process. The IRT subway, the 2 and the 3 trains, are represented on the map, but the Independent Subway lines now known as the A and F lines are not: they arrived in the mid-1930s.

The main difference between 1922 and today, of course, is all the streets that have been eliminated between then and now. Cadman Plaza, a lengthy, sweeping swath of green dotted by various monuments, occupies the space between Fulton and Washington (which have been renamed Cadman Plazas East and West), and took the place of Liberty Street and the west ends of Concord, Nassau, and High Streets in the 1950s.

The Farragut Houses, which appeared in the early 1950s between Nassau, York, Bridge, and Navy Streets, took out over a dozen streets shown here such as Charles Street, Green Lane, Talman Street, and many small lanes and alleys too small to be shown on the map. The character of some of the remaining streets were forever changed, such as Sands, which used to be Brooklyn’s equivalent of Boston’s Scollay Square—basically a place where workers and Navy personnel working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard found drinks and various types of entertainment.

Another knot of small streets west of Fort Greene Park—Bolivar, Lafayette, Fleet Place, and the east ends of Tillary and Johnson—were similarly eliminated by the construction of the Raymond Ingersoll and University Towers Houses, and by Brooklyn Hospital and Long Island University.

The 1922 Queens map, showing here the Long Island City section, is also considerably different from today’s version, but for different reasons. Virtually all the streets shown here still exist, but many if not most have been renamed.

The Queens Topographical Bureau decided to give Queens a proprietary house and street number system in the mid-1910s. The changes were rolled out gradually over the course of the next twenty years; during that time, street signs displayed the new street name or number at the top of the sign, and the old name at the bottom. However, elevated trains and subways in many cases opted to stick with the older names, at least partially. That’s why the N train has stops at 39th Avenue/Beebe Avenue (mislabeled "Deere" on the map); 36th Avenue/Washington Avenue; and 30th Avenue/Grand Avenue, and the #7 elevated has 33rd/Rawson; 40th/Lowery, 46th/Bliss, 52nd/Lincoln and 69th/Fisk. Even the Independent Subway, built in the 1930s, kept some old names such as 23rd Street/Ely.

Why did Queens opt to change to a unified number system? To avoid confusion. Success wasn’t always achieved, as there are spots in Maspeth where it seems every street is numbered 59 or 60. However, post offices were becoming confused as Queens gained population after the opening of the Queensboro Bridge in 1909. Separate towns, left over from Queens was just a county and not a borough of NYC, all had separate numbering systems, meaning there were numerous 1st Avenues, 1st Streets, 2nd Avenues, etc. Similarly, several named roads were duplicated such as Grand Avenue (Astoria and Maspeth) and Broadway (Astoria and Flushing).

The new numbering was said to emulate the Philadelphia system, as numbering of north-south streets originates there at the Delaware River and runs west. In Queens, numbering begins at the East River both at the west and north, with “streets” running north and south get higher numbers as you go east, and “avenues” running east and west get larger as you go south. In addition, so that numbered streets can maintain a general east-west and north-south course, intermediate numbered streets are inserted in a set order: Street, Place, Lane; and Avenue, Road, and Drive. Rarely, Courts and Terraces appear.

Queens is the only municipality in the country, to my knowledge, to have hyphenated house numbers. The first set of one to three digits before the hyphen indicates the street number, and the last two digits begins at 01 and runs as high as the last address between two streets.

Finally, the problem of duplicate named streets was resolved by unifying several main routes and calling them “boulevards.” For example, Jackson Avenue and Broadway were unified as Northern Boulevard; previously, Flushing Avenue in Astoria had become Astoria Boulevard. Prior to the new system, there were five separate Flushing Avenues in Queens, none of them particularly near Flushing (and the surviving one isn’t either).

The “new” system is far from perfect, but if you’re familiar with a neighborhood, you know you’re close to home when you arrive in an area with house and street numbers close to your own. Even if every street is numbered 60.