A couple of weeks ago, as my 19-year-old daughter was headed home from college for a long weekend and bringing along a friend, she texted to tell me that her friend "is gender non-binary and uses they/them pronouns." I want to call people what they want, and my fallback position is that people get to define their own identities and ought to be respected for doing so. But I found myself fucking up throughout their visit, verbally and also mentally. Not that I've never run into this situation before, but in the course of three or four days, I became vividly aware of the thoroughness with which man/woman gender dualism has been installed in my head. It became apparent very quickly that it’s almost impossible for me, at 61, to stop imposing the gender binary on everyone I see. I might not have been fully aware of how differently I treat, and how differently I talk to men and women, until I unconsciously and effortlessly tried to force Raphael to become a man. I'm apologizing to all concerned, but really I'm concerned that I, and perhaps we, cannot make ourselves think differently, even when I myself, and perhaps we, strongly believe we should.

Raphael read as male to me, in fact a pretty guyish male. So I took to saying things, to myself and other people, "His pronouns are 'they' and 'them.'" That was meant to be an expression of respect. All it showed me is that no matter what, I start the process of interacting with a human by assigning them a gender category: that's the first thing, my primary sorting procedure for people. "He wants to be called 'they'," is an unbelievable pre-erasure of someone's declared identity; I can't even get to the declared identity, because I made the gender assignment immediately and unconsciously. All weekend, as we streamed movies or drove to the farm stand, I addressed Raphael as “man” or “dude,” as in "Hey man, what kind of music do you like?" and so on (the answer, which surprised me, was "black metal"). They responded to this kindly, or without overt hostility. But meanwhile I just kept disappointing myself, and—I speculate—irritating them, or worse.

A college "women's studies" course often begins with the distinction between sex and gender, the former supposedly biological, the latter socially constructed. Plenty of people—most famously Judith Butler—have attacked this distinction in various ways, and Butler defines gender as a "performance," then says that the way we think about biological sex is an attempt to "naturalize" our constructed gender identities, to make them seem inescapable. And the ways that gender is constructed, and the supposed underlying biology, are volatile. For example, one might compare a country singer's, say Merle Haggard's, masculinity circa 1968 with Brantley Gilbert's masculinity now: with his long hair and jewelry, his extremely conscious self-ornamentation, Gilbert—a macho bro if ever there was one—would’ve been read by 1968 Merle as effeminate, as—in the contemporary parlance—gender queer. Now he reads 100 percent dude.

It’s worth thinking about how social constructions get constructed, or what it's like to have a social construction—like race, for example—fully installed in your head. First, it comes early, with your mother's milk, as it were. Second, for it to operate in your head thoroughly and effectively you have to cease being or never become aware that the thing in your head is a social construction. It appears to be just the way things are, so that doubting it or trying to tear it down doesn't seem to be a process of social reform, but a denial of obvious realities, and hence irrational and dangerous. If the social construction in question is oppressive or dismissive, that’s chalked up to objective and unavoidable truths. Insisting that it's optional, or throwing it into doubt, then appears false, irrational, and socially dangerous. And it is dangerous, because defying the categories shows them to be bendable, or optional; it shows the basic categories that are central to the ways we treat each other and think about ourselves aren’t natural and inevitable at all. Resistance to the gender pair, expressed in clothing and hair style, styles of movement or new uses of pronouns, is interpreted as resistance to fundamental realities on which the human world appears to stand: it shows the male/female and even gay/straight thing to be historical, optional.

That confronts each of us with the fact that our own gender identity is optional, in the sense that in another social situation it would’ve been quite different. People in various trans and non-binary gender identities seem to threaten the conventional identities, even one's own, in the sense that they show that these identities are not natural and inevitable. They raise the disturbing idea that even your own gender identity might be volatile, or that you might’ve gone, or might even now go, in another direction.

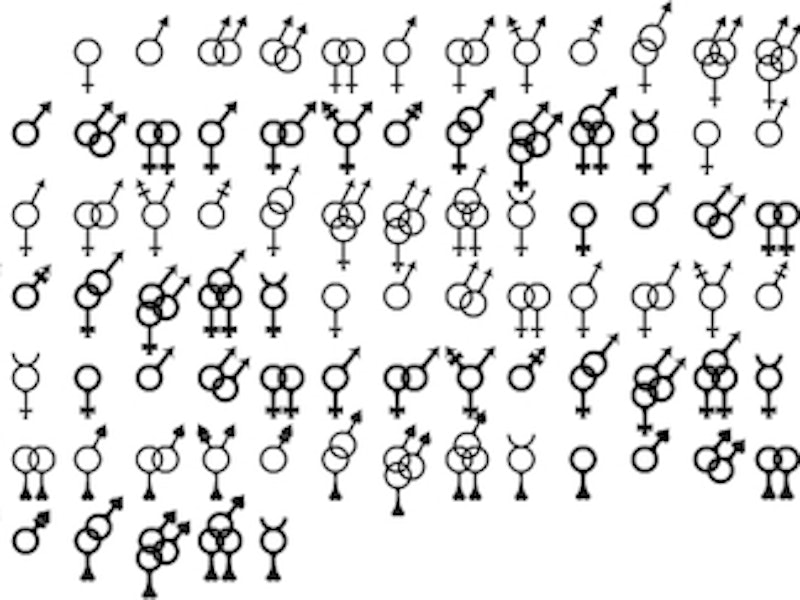

The idea that there are exactly two gender identities and that they are distinct from each other is profoundly oppressive. Men and women, boys and girls, have been defined in contrast with and in exclusion from one another. I think probably even in the golden years of the male/female split people yearned to manifest some of the qualities or engage in some of the activities associated with people on the other side. Men often yearned to nurture or have feelings, women to be independent or kick someone's ass. Our personalities, that is, were canalized in such a way that no one, in their heart of hearts, was merely one or the other. Someone who really was all-man or all-woman as understood in 1950, someone perfectly masculine or perfectly feminine, would be a sort of monster, a hypertrophic fragment of a human being.

We were always constrained by the gender binary, which was connected not only with structural oppression of the most obvious sorts, but also with self-oppression and self-division, or in general with narrow, rigid identities, always shoring themselves up in the face of threats of which people were apparently not aware, but which they were responding to all the time. Homo- and transphobia show this quite clearly: the sense that those people over there, as they do their thing, are putting your own gender identity under threat. They are, in fact, because they’re demonstrating that masculinity and femininity are not natural at all, and not tied in any clear way to biology. Also, the biology itself is complex and is getting more and more alterable.

What I realized about myself as I interacted with Raphael is that I'm one of those people whose whole way of understanding the human world and interacting with people is oppressive to them and myself, and also that I can't figure out how to stop, how to uninstall the buggy programs infesting my operating system. I can't, but I have a moral obligation to. The best I can do—and I intend to—is to try to slowly become aware of what I'm thinking, how I'm talking, and who I am, to slowly try to pry open my own categories and my own gendering.

That would make me a better person, and I may not have realized how badly I need to get better: that is, how evil some of the crap in my head, and much of the crap in our culture, really is. But prying open gender gives us all more options, or has the potential to open us up to the real complexities of our biologies, our world, and our selves, or make us less fragmentary and more open to the world and each other.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell