In the summer of 1978, a tall, young man stood on a Baltimore curb. A cowboy hat cast a shadow over a chiseled jawline framing a smirk. Good-looking would be an understatement. He swung a duffel bag over one shoulder then raised a thumb. Peter Haskell was a badass from Beaufort, South Carolina.

Among the many artists I’ve known, Pete was the kind of character you couldn’t invent. Most people probably haven’t heard of him, except for family members and a tight circle of artists who lived in Baltimore and Los Angeles.

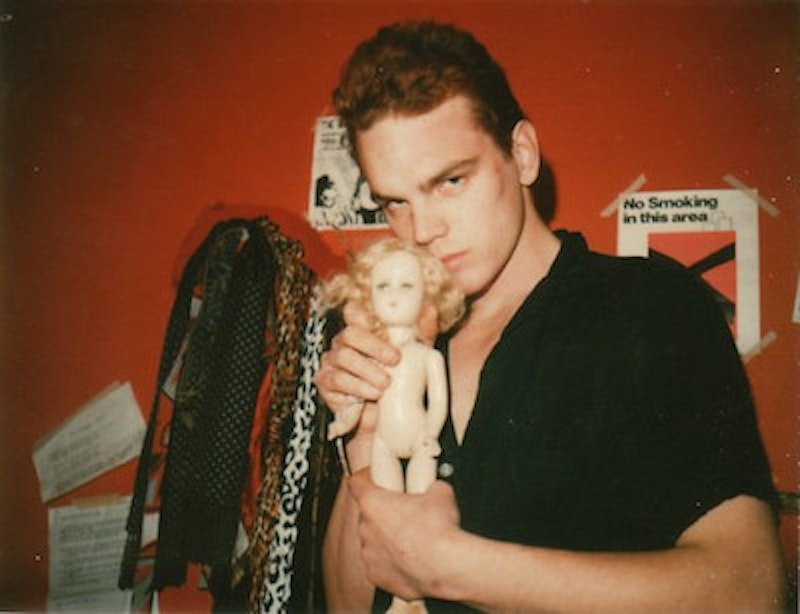

Pete was a roaming rascal—a punk cowboy who knew how to be a punk—a gifted, nonconformist artist and musician who lived life on one’s own terms. Everyone who knew Pete had a story.

His days in Baltimore were numbered. From what I saw, if there was ever a problem— Pete’s candor offered stinging wit as part of the solution. Southern nature I guess, his pedigree. Not one for the lame or trendy, at times he could be a man of extremes.

And for whatever reasons, Baltimoreans have a provincial way of looking at things. Everyone there’s blessed with an elephant’s memory. It’s always personal. Maybe they were jealous. Why? Because Pete had a non-secret: a go-as-you-please sense of artistic freedom. The real reason Pete left Baltimore remains a mystery.

Years later at age 51, Pete Haskell was murdered.

That late-1970s afternoon Tommy DiVenti was nearby. The poet/musician was busy taking a break. Sporting the Tommy look, he wore a pair of skank Converse sneakers, leather jacket and painted black fingernails. As he leaned against the H&H camping supply store window, fresh smoke rings circled his head.

His band Da Moronics just punk pounded a gig in New York at CBGB’s. I don’t recall Pete being there, but he drummed in an early incarnation of the infamous troublemakers with Bill Moriarty and Tommy. I first encountered Pete around The Maryland Institute, College of Art (MICA) and the Mt. Royal Tavern. We hit it off almost immediately. Pete was a welcome addition to many artists’ creative paths.

Little Chinatown was where Pete and Tommy lived in a onetime hooker hideaway on Eutaw St. above Hanratty’s Bar called “the loft.” We worked together around the corner on Mulberry St. at Martick’s Restaurant Francais. Life was a predictable if not dreamless routine, spooning bowls of onion soup and dressing plates of Coquilles Saint-Jacques.

Social times at “the loft,” were unrestrained. There was always an arty event happening: a film shoot, performance or reading. I shot Gang of 25 with Pete there.

But on this particular day, Pete was leaving. His main focus was on westbound US Route 40. Things didn’t matter much at that point. He had the “get-out-of Baltimore” virus, maybe a bridge or two burned. That was it. California here I come!

Tommy finished his cigarette and shouted, “See you later boss.” A car pulls over and Pete vanished. Baltimore’s art and music firebrands were at a crossroads.

By 1979, an exodus of Baltimore’s less well-known artists signaled a major change for most; from becoming relatively obscure to completely unknown. But for others, a chance to rise in Los Angeles. Big time.

By the mid-1980s, Pete had established himself in Los Angeles. It was the era of X doing a smashing cover of Wild Thing.

When it came to music, Pete had an impeccable ear. In 1986, he was the drummer for Thelonious Monster. He was also acting, directing and shooting videos. As an actor, how good? Muy bien. In Fingered, Richard Kern’s underground tour-de-force he kicks ass. It was only natural I’d catch up with my old accomplice upon my arrival in Los Angeles.

One evening in West Hollywood, Pete just shows up at my place. “Hey, what’s going on?” he whispered under anguished breath. Then Pete makes a beeline for the refrigerator and grabs a Bartles & Jaymes wine cooler, “Is this okay?”

“Yeah, sure.” I replied. After an awkward silence, “I’m shooting a music video for Barnes and Barnes. Need an extra.”

The next day we arrive at Raji’s, a punk dive on a sleazy block in downtown Hollywood. Barnes and Barnes is the music duo Bill Mumy and Robert Haimer. Their song “Fish Heads” was a highlight on The Dr. Demento Show. Yes, the same Bill Mumy from the TV series Lost in Space.

Immediately Bill, Pete and I set up an improvised pizza parlor in the bar area. The surrealist comedy Pizza Face stars the young, late Miguel Ferrer and bassist Flea. I’m the “all smiles” guy in a tux serving the pizza.

Wild things under the big black sun, that’s the way Pete rock and rolled Los Angeles.

I left California in 1988. Afterwards, not a peep from Pete. Word was he’d left Los Angeles at some point too.

Twenty years passed.

Then one day in the late spring of 2008, my phone rang. It was Pete, back again in Los Angeles, this time sounding psyched about a new publishing project. However, Pete’s comeback would be a short-lived, fatal decision. Hitting the restart button in your 50s proved difficult. In a struggle to get a break, I can only imagine how things grew increasingly hopeless with each passing day.

“Then I got tired of counting all these blessings. And then I just got tired.” A Song from Under the Floorboards—lyrics by Magazine.

There’s no murder mystery here, Pete knew his killer for a number of years. Both ran in the same incestuous Los Angeles social circles. Bruce Kalberg was a well-known figure throughout the Los Angeles art community. He started NO MAG, an infamous Los Angeles punk fanzine. In exchange for a place to stay, Pete had been promoting Kalberg’s new, semi-fictional book Sub-Hollywood. Kalberg died from leukemia in 2011.

Sadly, September 11th, 2008 would be Pete’s last day.

An evicted man went over to Kalberg’s place in hopes of collecting some personal items. Caught in a cockfight, a bitter quarrel escalated to an altercation. Pete was shot at point-blank range, one bullet directly to the heart. He hung his head and died. It was shattering news.

The official Los Angeles Police Department report from September 12, 2008: “On September 11, 2008 at about 2:15 pm, Hollenbeck patrol officers responded to a radio call of a possible homicide that occurred in the 1700 block of North Main Street. When the officers arrived, they located and detained the suspect, Bruce Kalberg. Medical personnel responded to the scene and pronounced the victim dead. Kalberg, 59-years-old was arrested and booked for murder. He is being held on $1,000,000 bail.”

Four days later Kalberg was released, the case dismissed. The Los Angeles DA ruled the shooting was self-defense.

Soon after Pete’s death came another surprise. One day a strange package arrived. The sender’s handwriting looked familiar. Pete Haskell! I carefully unwrapped several layers of paper, inside was a copy of Sub-Hollywood with a note. Was this a tap on the shoulder from beyond? I think Pete knew he was going to die soon. Shortly thereafter, I learned Tommy and John Waters also received similar packages.

Today barely a trace remains of Pete’s life and work. What little there is includes an LA Weekly feature by Paul Cullum and his sister Gretl’s memorial website.

It’s difficult to understand when an artist’s life suddenly fades to black. Just the other day, I saw wisps of white cirrus clouds form a portrait of Pete in the blue sky. That was the kind of deserved send-off he didn’t receive.