When I revisit Brooklyn’s 5th Ave., I’m going back to a stretch I’ve traversed thousands of times. Each day between September 1971 and the fall of 1980 I rode the B63 bus up and down the lengthy stretch to get to high school (Cathedral Prep in Bedford-Stuyvesant) and college (St. Francis in Brooklyn Heights) from my home in Bay Ridge, except for the days when I rode the B37 on 3rd Ave., the more boring of the two bus routes, or used the BMT R subway.

It’s tempting to say 5th Ave. is better now than it was. For many years 5th Ave. was mired in poverty, even as the rest of Park Slope south of it began a slow comeback in the 1980s. Entire blocks were razed and there were empty lots, just as there were in the South Bronx of the same era. Hundred-year-old brick and brownstone housing was deteriorating. It wasn’t until the 1990s that there was any momentum and the trickle of “urban homesteaders” who bought along 6th and 7th Aves. and the side streets in between began to invest in 5th.

Gentrification has benefits and drawbacks. As property values and rents increase, the people who got in early are reaping great rewards. But people with incomes like me, who had earlier avoided streets like 5th because of the former forbidding-appearing conditions, are now priced out with no hope of ever affording it, and some longstanding residents are forced out by the changes. It’s the story of New York City. One extreme or the other, and nothing in between.

So can you get me to say 5th is better than it was from 1971 to 1980? The buildings have been spiffed up and there’s active local business. In the old days, people lived, worked and went to school here, not thinking they were merely scene-setters for a new group of urban professionals, and had to make way for their “betters.” Class envy?

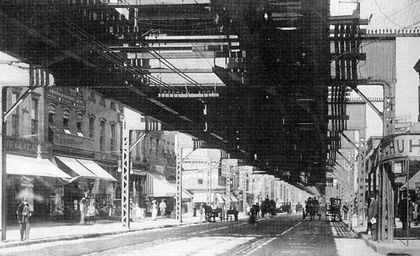

Above is a view of what 5th Ave.’s northern end at Atlantic Ave. looked like in 1962. It’s hard to believe it now but this was Brooklyn’s former meatpacking district. Here, big names in the industry such as Swift and Armour packed poultry and meat products and if I’m not mistaken, there were slaughterhouses here as well. On those rare occasions when I walked to and from high school from here in the 1970s, I’d have to avoid huge hunks of beef swinging on meat hooks. Unfortunately I didn’t usually carry a camera then. The platforms of the Long Island Rail Road Flatbush Avenue terminal are under the street. Today, the area’s dominated by the Atlantic Terminal shopping mall and the gargantuan Barclays Center sports arena.

Flatbush Ave. cuts through Park Slope grid at an angle, creating many irregular plots. Triangle Sports has occupied the only building in the triangle-shaped plot here for nearly 60 years (the actual building, though, has four sides). Triangle also had a Bay Ridge branch on 83rd and 5th for many years; my mother bought my Cub Scout uniforms there. (Above picture from Brian Merlis and Lee Rosenzweig’s Brooklyn’s Park Slope: A Photographic Retrospective.)

Our principal interest is in an older shot, taken in 1914, the structure in back of the Triangle building: the 5th Ave. El. Brooklyn once had four elevated lines that didn’t connect with its subways except by transfer: the 5th Ave. el, the Fulton St. el, the Myrtle Ave. el, and the Lexington Ave. el. None survived past 1969. Riding 5th Ave. buses for over a decade, I had no idea it was once covered by an el.

It’s easy to say that the BMT 4th Ave. subway a block away put the 5th Ave. El out of business, but the 4th Ave. was built in 1915-1916 by the same company that operated the 5th Ave., and the two lines coexisted profitably for almost a quarter century. Possibly, the Great Depression sounded the el’s death knell. Almost immediately after the el’s demise, its pillars along 3rd Ave. between 38th and 65th Sts. were employed to carry the roadbed of Robert Moses’ new baby, the Belt Parkway (assuring that 3rd Ave. would continue to be in the shadows—which would be extended all the way to Hamilton Ave.!) In the early-1960s, these el remnants would disappear as well, as the Belt in Sunset Park was reconfigured as the Gowanus Expressway, leading to the new Verrazano Bridge.

Carroll St. (like the one in Baltimore) is named for Maryland representative at the Continental Congress, Charles Carroll (1737-1832). He was the sole Roman Catholic signatory of the Declaration of Independence, was at his death the last surviving signer, and the only one to include his hometown in the signature: “Charles Carroll of Carrollton.” He’s honored with a street name because of the Maryland troops who assisted in the Revolutionary Battle of Brooklyn at the Old Stone House in J. J. Byrne Park, between 3rd and 5th Sts. and 4th and 5th Aves.

What’s now called the Old Stone House was originally constructed in 1699 by Klaes Arents Vecht, who arrived from Holland in 1660. The house remained in the Vecht family until just prior to the American Revolution, when it was rented to an Isaac Cortelyou; his father, Jacques, bought the property in 1790, and the house continued on with the Cortelyou family until 1850 when it was sold to Edward Litchfield.

Apparently, Litchfield allowed the house to sink into ruin: by the 1890s only its upper floor was visible above ground level. The house was demolished in 1897, though its original construction was so tough that Gatling guns were used to force the old stones apart. The house found an angel in Brooklyn Borough President John J. Byrne. The Old Stone House’s original foundations and brick were rediscovered, and Byrne, in one of his final acts before his death in 1930, ordered its reconstruction in a park posthumously named for him in 1933. The Old Stone House received a thorough makeover in 1996 with new plumbing, electrics and roofing installed.

The Old Stone House had played a pivotal role in the American Revolution. On August 27, 1776, during the Battle of Brooklyn, things looked dire for the Americans, as the British and their hired hands, the Hessians, were overwhelming them in what’s now the northern section of Prospect Park. Hoping to reach forts at Boerum Hill and Fort Greene, about 900 American troops retreated from what would be the Greenwood Cemetery area; they hoped to track northward. General William Alexander, aka Lord Stirling, led a company of 400 Maryland troops that engaged British General Charles Cornwallis’ force of 2000 grenadiers and cannoneers at the Stone House to cover the retreat and, while many of the Americans were able to escape, Stirling was captured and 259 of the Maryland troops were killed.

When I passed this storefront at 372 5th Ave. near 5th St., I assumed it was an elaborate movie set or an expensive joke, but it turns out “Brooklyn Superhero Supply” is a spiffed-up tutoring center for neighborhood kids, known as 826nyc, that opened in June 2004. Why 826? It’s an offshoot of an original center on 826 Valencia St. in San Francisco. It was started by belles-letterman Dave Eggers.

Prospect Ave. was once called Middle St. and forms the boundary between what some consider the North and South Slopes. Near 5th Ave., it’s dominated by the Grand Prospect Hall, built by John Kolle in 1892, the big white building seen here opposite the Prospect Expressway. It was originally an entertainment palace with assembly hall, theater, bar, restaurant and lodge rooms. After a 1900 fire, it was rebuilt and enlarged in 1903 with bowling alleys, a billiard room, a German-style oak-paneled beer hall, meeting areas, an open-air roof garden, dining rooms and a 40-foot-high ballroom.

By 1981 the Prospect had fallen on hard times; that year, Michael and Alice Halkias purchased the building and have since spent millions into making it Brooklyn’s premier catering hall. Their TV commercials in which Alice proclaims, “We make your dreams come true” are unavoidable.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)