This is a response to a column I wrote last week about the increasing irrelevance of the novel, as argued by Will Self. I thought his piece in Harper’s amounted to little more than another old man yelling at the cloud, as Self readily admitted. He argued that novels have become “skeumorphs,” or an image that depicts an obsolete object (a telephone receiver) in order to represent a modern device or function (the phone icon on every smartphone). I don’t agree that contemporary novels are mostly “recursive quilting,” read and written about exclusively by academics and an ever-diminishing group of pure enthusiasts.

The printed page is surely on its way to becoming like painting or classical music, a “conservatory practice,” or like vinyl records, a niche object brought back from the dead and cherished for all the qualities that led to its replacement—size, sound quality, what it demands from the user. I feel confident in saying that books, and novels, will be around for the rest of my lifetime, but clearing the enthusiasm hurdle is going to get harder as years go by. At this point, I’d rather focus on working through Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, the Brontës, and Barth than waste any more time on alt-lit or middle-of-the-road novels about the housing crisis or the war or the Great Recession.

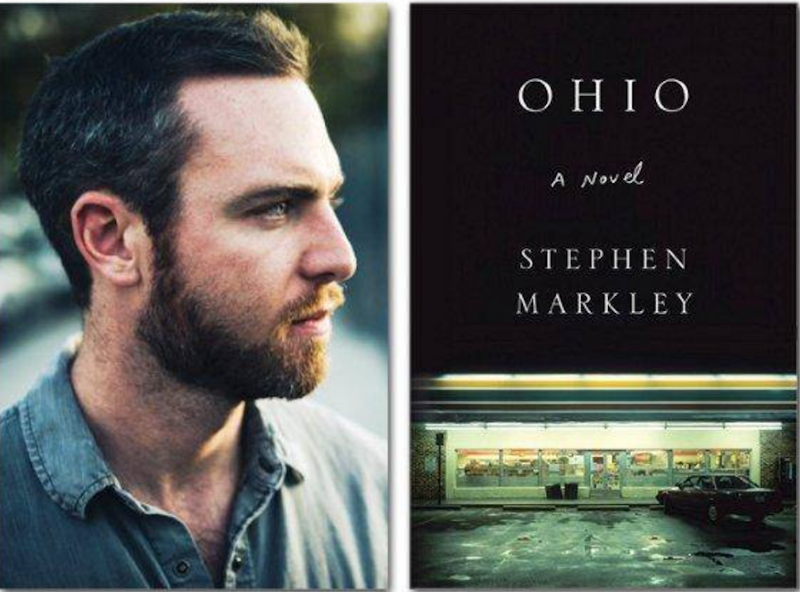

My dad gave me a copy of Stephen Markley’s Ohio for a potential review, but I couldn’t get through more than 80 pages. On the latest episode of Bret Easton Ellis’ podcast, he said that in novels, “tone is everything,” and that plot can never save a poorly-written or aesthetically uninteresting book. I tend to agree, and applying an 80-page rule to new books I read is not only more generous than they deserve, it’s helped me narrow down what I’ll be spending my time on.

I’m eager to be proven wrong and surprised: in 2015, I clowned on Jonathan Franzen for nearly adopting an Iraqi orphan but ultimately following his agent’s advice that it would be a “bad career move.” I hadn’t read any Franzen at that point, so I bought Purity and actually liked it a lot. I read his 2010 novel Freedom immediately after, and it stunned me: like Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, it’s a multi-generational epic that taught me something valuable in its time-hopping structure: we can never know all the details of our parents’ life stories before we showed up, and that so much of the angst and frustration and pain that we deal with in families comes out of ignorance, a lack of empathy borne out of a lack of understanding of where they’ve been before and what they learned, what scared them and what formed them.

Freedom, like a lot of Franzen’s work, is very much a Midwest book, and Franzen’s concerns and tics are distinctly Midwestern. Markley’s Ohio shares superficial details with Franzen—the desiccated small towns, big box stores, alienation of suburbia, the very provincial and white milieu the characters inhabit—but I don’t like his writing at all. Markley reads like a wannabe Bret Easton Ellis or Franzen trying to be edgy.

On breaking up in high school: “You fucked like a corporeal toast to the heartache of new beginnings.” On nostalgia: “This picture had taken a mercurial path. Many times he’d thought of leaving it wherever the wind happened to have blown him.” Using the phrase “the thing of it” to begin a sentence. A painfully un-cool Midwestern observation two decades stale: “a wildly foul mouth that could employ the word fuck as a noun, verb, adjective, or gerund in a way you were sure had never existed before that moment (‘Having us a fuckly good time,’ he’d said, as they sat in the grass, staring out at the glistening midnight sheen of Jericho).”

This isn’t a book review, or an attack on Ohio or Markley, merely testament to Will Self’s point that novels will inevitably diminish in relevance and popularity because of the time and attention they demand. I read a lot, but 80 pages in, I can tell when something isn’t doing it for me. If Ohio were a movie, I’d sit through it if only because it couldn’t possibly take longer than reading 80 pages of this book did. I had the same issue with Jonathan Dee’s The Locals last year, which starts out narrated by a hilarious layabout in New York City before switching to third-person omniscient, following a very boring couple in the suburbs. I have at least a dozen books going at the moment, and there just isn’t enough time to slog through something that isn’t working for me aesthetically. I know I’ll miss out on the “shocking” and “violent” ending, but it’s just not worth it. No harm in trying, but no shame in giving up a book either.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith