I still love Rich Mullins. The late Christian singer/songwriter may be best known for the dreadful “Awesome God” (which even Mullins admitted wasn’t one of his best songs), but the rest of his catalogue is much better. His music mixed elements of classical (“Sing Your Praise to Lord”), Celtic (“The Color Green”), and African music (“How Can I Keep Myself from Singing?”), which made him stand out from most garbage Christian music. He was also brutally honest; at concerts, he stood onstage barefoot and unshaven, shared his thoughts between songs about how the Church had strayed far from Christ’s message of grace, and openly talked about his own flaws.

Brennan Manning’s book The Ragamuffin Gospel was a huge influence on Mullins. Manning was an ex-Franciscan priest whose lifelong struggles with alcoholism led him to a deeper appreciation of God’s grace. “To live by grace means to acknowledge my whole life story, the light side and the dark,” he wrote. “In admitting my shadow side, I learn who I am and what God's grace means… My deepest awareness of myself is that I am deeply loved by Jesus Christ, and I have done nothing to earn it or deserve it.” It’s this message of radical grace that I miss the most about Christianity.

Everything else about Christianity I could’ve done without: trying to make ancient texts relevant for modern times, hearing nothing but silence after begging God for guidance, feeling ashamed for not wanting to wait until marriage, etc. Even the positive aspects of the faith—community, music, and wonderment—can be found outside the Church. The only thing missing is a secular version of the idea that God is picking up the broken pieces of my life and creating something beautiful from the mess. What does it mean to live by grace as an atheist, or is it even an option?

David Ames blogs at Graceful Atheist and hosts the podcast of the same name, both of which center around a concept he calls “secular grace:” loving people the way they are, without being commanded to do so by a god. “When I was a Christian, I was a grace junkie,” Ames writes, “and I stayed a Christian much longer than I would have without my understanding of grace. I understood on a deep level my need for acceptance.”

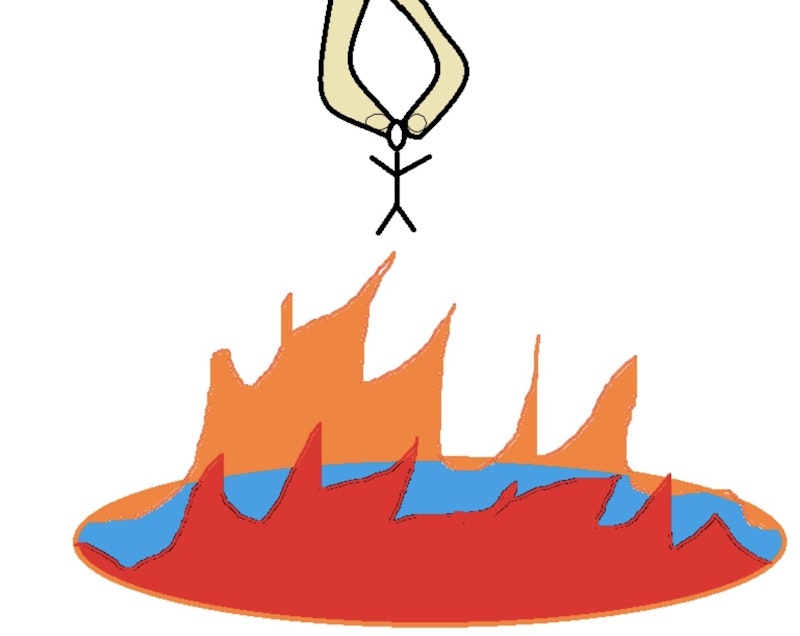

The Christian message of salvation through grace alone seems liberating at first, Ames explains, but it’s heavily flawed. Certain theologies, like Calvinism, overemphasize the total depravity of humankind, making parishioners feel like they personally killed Jesus. One of the most well-known examples is Jonathan Edwards’s infamous “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” which contains such graphic depictions of Hell that congregants moaned and wailed when he first preached the sermon in 1741.

I first read Edwards’s sermon in 11th grade English when we were studying the Puritans, and I wondered how anyone could worship a God who dangled people over a fiery pit like spiders. A year later, my then-girlfriend presented an alternative version of God, one that wasn’t threatening me with fire and brimstone, but was instead waiting for me to return to him as a prodigal son. Eventually, this didn’t make sense. Jesus dying just because we’re all imperfect people sounded overly dramatic. The doctrine of original sin began as a reassurance that everyone else is as screwed up as me, but slowly became a daily reminder that my fallibility was a curse.

Humanists, on the other hand, believe that people are neither good nor bad by nature, but instead can do both good and bad things. We can all live ethical and fulfilling lives without God. We’re still capable of fucking things up, though, which is where secular grace comes in. “We need to be gracious and empathetic with one another,” Ames writes. “We need to acknowledge our fallibility [and] even embrace it. Admit when we are wrong quickly and not beat ourselves up over it.”

I’ve done enough shadow work to know I’m neither an angel nor a demon, yet this binary is hard to break. Yet being a humanist means affirming the inherent worth and dignity of all people, despite all the messiness, so maybe the best place to start is with myself. The only way forward is to embrace my true nature—a ragamuffin humanist—and live by self-grace.