Last night I dreamed everyone was here for the wrong reasons. I was an aspiring dental hygienist from North Dakota on a TV show with 25 surrealists and a Texan named Fred who were all living together in a house in Hollywood, competing for my hand. Some, like Man Ray, wanted only my hand.

“For a collage,” he explained, before kissing it.

It was the cocktail party before the third rose ceremony and I was nervous, unsure of who among the remaining 12 to send home.

“What a peculiar name, Man Ray.”

“They call me Man Ray because I shoot Man beams from my Man eyes.”

Magritte appeared in the doorway. “Can I steal you for a second?” he asked with his back to me. He’d placed a pair of sunglasses over his hair and was raising them up and down provocatively.

Ray rolled his eyes. Magritte took his place.

“Non,” he said, handing me one of two mirrors. “That way,” he said, suggesting I face away from him. “I learned this trick from my barber. Look in your mirror,” he instructed, “and find my eyes looking into my mirror looking into yours.”

Our eyes met in the glass. “May I kiss you?” he asked after a long pause. He leaned in. So did I. The glass was cool against my lips. When I opened my eyes he was gone.

In his place, sat Aragon. I dropped the mirror and turned to him.

Aragon stared ahead and said nothing.

“I feel our relationship is not moving as quickly as my relationship with some of the others. I know so little about you. What is it that you do again?”

“I’m a writer,” he hissed. “I nap.”

I smiled and laid a hand on his knee. “You seem upset.”

“It’s not my intention to throw anyone under the bus, but you ought to get rid of Gide. He’s ‘a bothersome bore’ and not here for the right reasons.”

Dalí appeared. “May I steal her?” he asked, mustaching his twirl.

“You may borrow her,” Aragon snapped. “It’s not stealing if you obtain permission. If you need me,” Aragon said, “I shall be in the fantasy suite, preparing my treatise.”

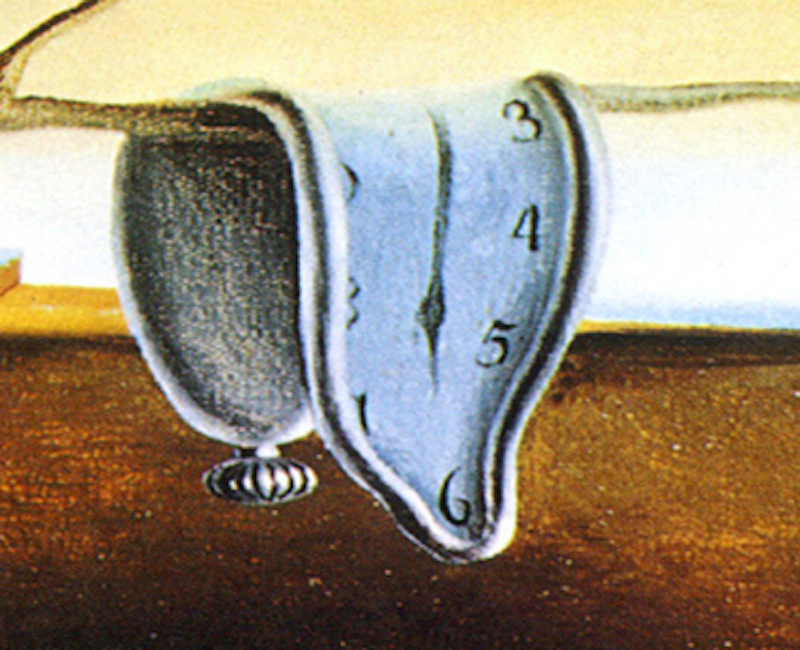

Dalí proffered his arm. “Come!” he said, leading me into the kicthen. On the stove bright flames licked a festival of silvery pots. One at a time Dalí removed their lids revealing clocks, all the clocks in the house, boiling in their juices. He took my hand, brought it to his chest. “Can you feel me ticking? You’ve melted my heart, the way I’ve melted these clocks.”

“Beat it, Dalí!” said Aragon from the doorway.

“I wanted to give you something,” Aragon continued. “My last book.”

I read the title aloud: “Irene’s Cunt.”

It’s the collected sex columns I wrote for Men’s Heath. Irene’s my ex. I spit on her bourgeois nothingness; she married a doctor—ha!—as if we aren’t all going to die anyway. If you marry me, I’ll write only of your cunt, of its snapping teeth, its lettuce like hair…” He was on his knees, waxing vegetarian, when Pierre Reverdy walked in. “Can I steal you?”

Aragon growled.

“I want to marry my best friend,” I told Pierre once we were alone.

Pierre replied, “‘The more the relationship between two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the [marriage].’”

“Opposites attract, in other words.”

He nodded and kissed my hand.

“Artaud calls the rose ceremony ‘The Theater of Cruelty.’ Do you think I’m cruel?” I asked Pierre.

“Just enough,” he said, his lips grazing mine.

André Breton walked in. “I need to talk to you about the drama in the house. Aragon sent a nasty letter to Fred.”

“Fred, the part-time personal trainer and children’s party magician from Texas?”

“The one.”

He removed a folded page from his breast pocket and began reading. “‘Dear Scumbag: I find you to be obscene, asinine, and above all, lying and cowardly. I have no intention of arguing with a lardhead. The mere idea of your kind of trash stinks… and you yourself… smell to high heaven. I’m telling you this very gently: I respectfully stop up my nose in the presence of your goatee.’” He refolded the page and placed it back in his pocket.

“I don’t think Aragon is here for the right reasons,” he continued. “I’ve drawn up a second manifesto detailing the right reasons.” From out of his breast pocket, he produced a second sheet. “Shall I read it?”

I closed my eyes. When I opened them, I saw Magritte holding a pipe. “This is not a pipe,” he said and walked out.

Voices in the hallway drifted into the living room. I edged closer and found Breton hunched in close conspiracy with one of the show’s producers. “‘I believe in the future resolution of dream and reality,’” Breton confessed. “‘A surreality, so to speak, I’m aiming for its conquest.’ If she does not choose me, I think I’ve got a good shot at being the next Bachelor.”

I returned to the kitchen and to check on the clocks, when I remembered the old axiom—a watched clock never boils. When after 10 minutes no one had come to steal me, I wandered into the living room where all the bachelors were gathered before Aragon, who was reading aloud from the Treatise on Style he’d written for GQ.

“Mustaches out. Sock garters in. Long pants out. Cravats in… Automatic writing out!” he cast a serious eye about the room.

I shook the ice in my empty glass. Startled, one of the men on the sofa turned, revealing the head of a rooster.

With his beak pointing straight at me, Ernst rose up in full tuxedo.

He rushed to my side and whispered in my ear. “Tell me your dreams!”

“I’m an aspiring dental hygienist and am hoping, once I finish school, to find a position within a good practice and get married and have a family.”

“No, from last night!” Ernst said, leading me out to the patio.

“But I never remember my dreams.”

“Then I must take you to the fantasy suite!”

“I’m not that kind of girl.”

“We will sleep together and when we wake, we’ll write down what we’ve seen. The path to the soul is through the unconscious. There, the soul will find its mate. I love you!” he appended quickly.

“‘What is [love]’ anyway? Aragon boomed, appearing, skeptical, in the doorway. “‘Let me begin by explaining what [love] is not… [Love] is not the poison of strong souls, nor is it strong fish glue... [Love] is not a lantern, nor does it come to those who wait... It is not horrified by ghostly apparitions. It is not surprised by a pianist... Nor—as one might be tempted to conclude from all this—is it a state of mind.”

“What is it then?” Dalí inquired, exiting the kitchen.

“‘It is not the rosin of wit nor the cuckoo of perfect timing,’” Aragon answered. “‘It is not the telephone of days gone by... Nor is it a way of recouping oneself, and I ask you is it possible to recoup oneself?’”

Ray shrugged and threw back what was left in his glass.

“‘[Love] is not a clown,’” Aragon went on, motioning to Fred, who was making his way toward us. “‘Not a swallow, not speaking Latin, not falling asleep on one’s feet,’” he motioned to Gide, who’s eyes were closing from drink. “‘It is not nincompoop, not dandelion, not...”

“Come with me!” Fred said suddenly, sweeping me over to the pool.

“Watch!” he began, once I’d sat down. He removed a long string of colored handkerchiefs from his right pocket and began stuffing them into his mouth and then removing them again from his left pocket. Then he crouched low beside me, and took the arm of my chair between his teeth, lifting me in it, high off the ground. After a moment, he put me down and confessed: “In my dreams, I am a contestant on a game show, but I don’t know the rules or the prize. I am living in a house with 25 competitors and every day one of us is sent home. We are judged by vague if exacting criteria. I’m attacked from all sides. I say things like, ‘Don’t throw me under the bus,’ ‘This is who I am as a designer,’ ‘It is like a fairy tale’ and wake up screaming. Am I dreaming now?” He pinched me. “Can you feel that? Let me take you away from here, out into the real world where we can appear in Peoplemagazine shopping for groceries like a normal couple, and together plan a modest, nationally televised wedding.”

Just then, we were interrupted by a foghorn. “Come,” I said, standing up. “The Rose Ceremony is upon us.” The foghorn blared, blending into the sound of my alarm clock. I hit snooze. Two, three more times, I snoozed, each time returning to that Hollywood house, to those exquisite bachelors, and to my choice.

“Aragon is still in love with his ex…” “How do you know?…” “He’s been writing about her again… Irene’s Cunt Deux…”

I tossed and turned.

“‘There is only one difference between a mad man and me,’” Dalí announced, staring into my eyes. “‘I am not mad.’”

I turned and tossed.

The Rose Ceremony, the theater of cruelty. Magritte among the others, with a sheet over his face. One after another I called their names: Artaud, Ernst, Duchamp... “Will you accept this rose?”

I do not call Aragon’s name and he leaves, climbing into a glossy black limo. Inside, tears stain his face, as he speaks, no longer to me, but to the camera:

“She asked me ‘What color are your dreams? A fool’s question... Her dreams were blue...’ I am not the man of them apparantly. I am not blue. I do not blame her her stupidity, just as I do not blame a flower its leaves. She is not for me... I try to believe someone is, though often I feel like ‘a man who does not hold the key to a door that does not exist.’ And now, I am humiliated again. ‘One might wonder what bizarre advantage I stand to gain by this incomprehensible trampling. One might wander,’ and one might learn when one tunes in four weeks from now for a very special episode of ‘The Men Tell All’.”

—Follow Iris Smyles on Twitter: @irissmyles