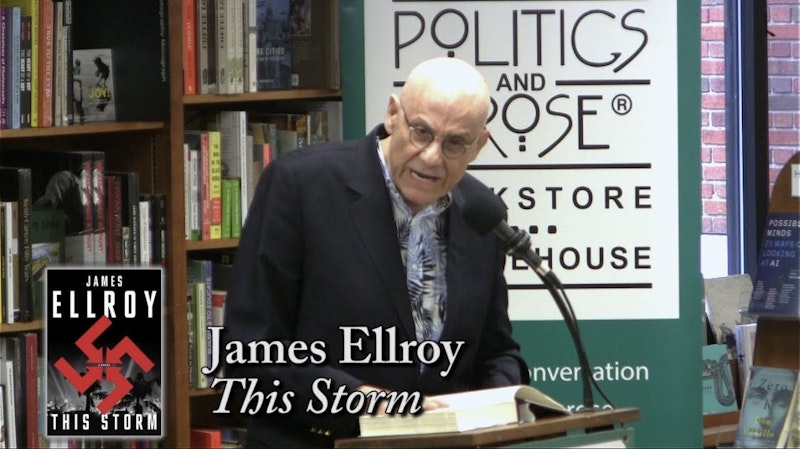

Walking along Main Street in our down-on-the-heels town I stopped outside a pet-shampoo establishment to look at a table covered with merchandise. The old Harris eagle eye zeroed in on two “finds”: paperback versions, in pretty good condition, of John Banville’s The Infinities and James Ellroy’s This Storm. Sometimes you get lucky.

My luck intensified when I ducked my head into the establishment and the proprietor—middle-aged, long-haired, and as ragged as the sort of mangy dog who might require a medicated bath—told me that the books were free. A $20 value—and this Midwesterner, penny-conscious to the core, left with his wallet no lighter.

Banville consistently delivers. The Untouchable, his novel based on the life of that wonderful-cultured Russophile and true European, Anthony Blunt, was his masterpiece, but Shroud and Mrs. Osmond were also commendable. When I think about it, it’s amazing that a Banville, a man of letters in the old-fashioned sense, should still be working and publishing in this philistine age. More power to him.

As for Ellroy, I was onto him in the 1970s, having drifted in his direction after exhausting the collected works of Hammett, Chandler, and MacDonald. I didn’t last long with him back then. At that point, the man couldn’t write. I don’t mean that in any complicated way. It wasn’t that he couldn’t write as a matter of structure or plotting, even though he couldn’t do that either. It was rather that he seemed not quite grammatically competent. Pick up a copy of one of Ellroy’s early works, such as Killer on the Road or Because the Night, and you’ll see what I mean. The clumsiness of the language on the level of word choice, syntax, etc., is remarkable. I’d say that those books seem to be written by someone for whom English was a third language, but that would be insulting to Joseph Conrad, and indeed for Vladimir Putin, who I’m appraised is a fine stylist in English (his second language being, of course, German). Anyway, Ellroy’s early books were unreadable. I bounced off the opening chapters of at least three of them before disposing of them.

Then a small miracle happened. Ellroy developed one of the strangest and most interesting narrative voices in postwar American fiction—which admittedly isn’t saying much, but it would’ve stood out under any circumstances. The Ellroy narrator—a bigoted and omniscient beatnik, spewing out mid-century hipster slang and elaborately offensive racial and ethnic epithets as he reports from the moral disaster zones of Los Angeles and elsewhere—is a fine literary invention. As I’m not the first to ask: just who is the offensive, jive-talking, obsessive-compulsively repetitive maniac who narrates Ellroy’s books supposed to be? No matter. That voice made all the difference and is much of what makes books like American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand so much fun to read, helping elevate them far above the usual genre material.

The fact that Ellroy learned how to tell a story, driving his plots forward with a cascading, energy, didn’t hurt. Nor did the implicit view of U.S. history that Ellroy’s later works put forth, a view that’s dear to my heart. Ellroy depicts postwar America as a violent cesspool, a hell of total corruption, a place 99 percent of the spectacularly ugly history of which took place in secret as a matter of conspiracy, beyond the sight of the average citizen. That sounds about right to me. Upon finishing American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand, which propose an eerily convincing alternative history of the Kennedy years as an era the driving element of which was psychopathy, I wished that the book was taught in high school U.S. history classes as a standard factual account of the period. “What?” you spit. “But the book isn’t true.” My retort is that it expresses a higher truth.

A word on Main Street in our Indiana town. It had been declining for decades, but the pandemic dealt it yet another blow. Empty storefronts are everywhere, and the businesses that are there seem like they’ll be short-lived, such as a tanning parlor and the doggie bathhouse the proprietor of which (God bless him) did me a good turn. The hardware store and grocery are both gone, victims of the big-box retailers on the outskirts of town, and those are the sorts of businesses that can ground a town and give it its identity.

Neo-liberal capitalism continues its assault on decency.