What force moves the writer Elizabeth Gilbert to boycott peoples and nations? What force moves her to boycott and apologize for her own work too? What force is so strong as to weaken her will and cause her to withdraw her latest work? Why must she force herself to hold her piece until Ukraine secures a just and lasting peace with Russia? Why must she do to her novel what the state does to innocents in her novel, subjecting the good to the cruelties of man and the caprices of nature?

The questions may confound Gilbert as much as her words confound and shock the conscience of readers. Here’s a writer whose life is foreign to how most people live or make a living, and whose remembrance of the past bears no resemblance to what isn’t even past, as she tells the world that she had a very good plague year.

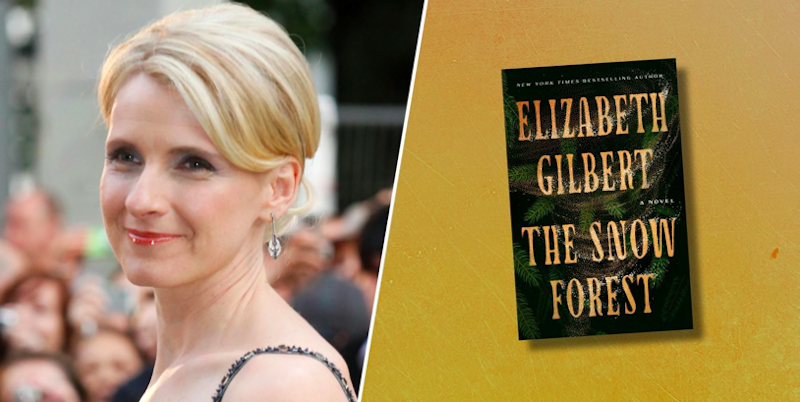

Gilbert found love in the time of Covid, or rather she found that she loved the silence and isolation of this magical time. She also found that she loved an extreme version of this fantasy, drawing inspiration from history while defacing it by other means. The result’s a whitewash as severe as any whiteout in the snow forests of Russia, where the history of one family’s retreat from Soviet persecution becomes Gilbert’s tale of historical fiction.

So much for the cunning ability of the divine feminine to outwit totalitarian patriarchy, as Gilbert halts publication of her novel and concedes that now isn’t the time to release a book—any book—that’s set in Russia.

Lost on Gilbert is the cost of her holiday from history, as she begins her first summer in the Siberia of the midnight sun.

Gilbert’s exile is virtual and voluntary, far from the dead of winter and the shadow of darkness at noon.

Distance affords Gilbert the luxury of escape, freeing her from the cold without making her a prisoner in her own home, because she can change the temperature and control the instruments—the devices—of tyranny.

She can dim the picture or shut it off completely, freeing herself from the enemies of freedom, or she can defame the living and desecrate the memory of the dead.

She sins against truth, assigning guilt according to blood and finding all Russians liable for the most grievous sin.

Gone is the need to see or know the truth, for Gilbert’s verdict is final.

She intercedes for neither 50 righteous nor 10, delivering 146 million souls to the same fate.

Before Gilbert sweeps through Russia, destroying the grasslands and salting the steppe lands, before she levels the Urals and unleashes on Moscow, she should save the trees.

She can mill the wood and make caskets of Siberian fir, aspen, spruce, and pine, giving the damned what they deserve: the dignity of a proper burial.

Perhaps it’s wrong to question Gilbert’s plans with words of knowledge, or to tell her that words are nothing without knowledge, but words are the tools of her trade.

To use the tools to do wrong is Gilbert’s right; to say nothing about what she writes is to wrong the victims—the poets and priests, the printers and playwrights—a second time.

Gilbert’s words are like the mists of make-believe, fleeting and false from beginning to end.