I have a sleep timer on my phone that connects to my Apple Watch. It measures, in hours of sleep debt, how far behind I get during the week and how eagerly I catch up every weekend. It’s probably the worst $3 I’ve ever spent, because I’m never exactly at zero, and I’m always worried about sleeping too little.

Take, for example, the three-day weekend that just passed. By Sunday morning, my sleep debt was completely paid off, and I was at zero. So how can I explain what happened next? I drank coffee in the middle of the night, stayed up watching movies, and then rose at dawn for a croissant and a long dalliance with Balzac’s Lost Illusions. I welcomed the prickle of fatigue that nipped at me as I continued on into the afternoon, writing a review of a new show on Netflix. I was ready for the tiredness. You could even say I needed it. Yet my watch and app were back to a state of resentment and concern, all the more so once I decided to spend the night rolling Suntory’s “Toki” whisky around on my tongue.

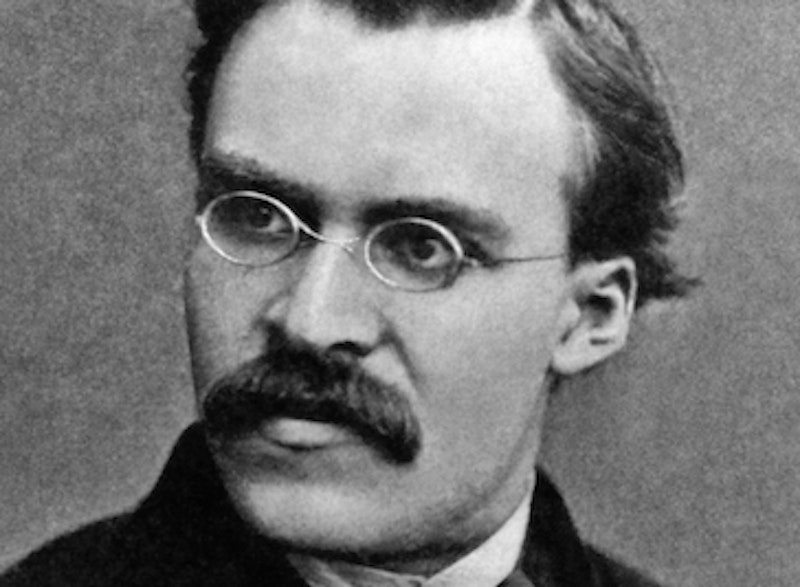

“It’s a downgoing.” That awkward transliteration of the German word Untergang, in Walter Kaufmann’s translations of Thus Spake Zarathustra, has stayed with me ever since I first read Friedrich Nietzsche’s epic poem. “Downgoing” is more kinetic than the more plausible word “descent”—you can see bold Zarathustra leaping from his aquiline heights to laugh, drink, and play among the people who inhabit the broad, low plains. There’s an elitist edge to the concept—we are talking about Nietzsche, after all—but it’s less offensive when you consider that we all have cycles of holy restraint and happy descent, and little choice except to smile knowingly at our own patterns. I need a little sleep debt to make me feel rebellious, hard-working, and alive, just as I much as I need long lazy nights of dozing, afterwards, in order to keep my wits about me.

In Michel de Montaigne’s essay, “That the taste of good and evil depends in large part on the opinion we have of them,” he writes: “How many do we know of who have fled from the sweetness of a calm life at home among people they knew in order to undergo the horrors of uninhabitable deserts, throwing themselves into conditions abject, vile and despised by the world, delighting in them and going so far as to prefer them!”

Montaigne might’ve added that this is not a choice we make for once and all, living the rest of our lives in extremis, but rather a part of a larger cycle of challenge and rest, of ambition and resignation... of hours first passionate, then tranquil. We expend tremendous energy chiding ourselves for the more exuberant, shameful, and unsustainable aspects of our nature, as if these were less essential than the rest. But downgoing is more than a mere compulsion. It’s the prelude to a feeling of limitless possibility.

Of course, even I tremble a bit writing these words, because I wouldn’t want sex, caffeine, or bursts of productive madness to become overly predictable moments in a once-again dreary and unvarying routine. Something in me instinctively tries to keep such blisses away from my own constant, instinctive tendency to domesticate everything through tolerant analysis. But that’s as anxious, and as foolish, as trying to stay lofty and healthy and highbrow all the time. The fact is that our quality of life depends to an extraordinary extent on our own gradually composed narrative about what we do and what befalls us.

As Montaigne observes, “No one suffers long, save by his own fault. If a man has no heart for either living or dying; if he has no will either to resist or to run away: what are we to do with him?” To understand life as a series of incompatible moments in juxtaposition, and to live it like that without causing inordinate pain: that is the philosophical definition of happiness in an age where we are wise enough to value life rupturing us.

We’re not only striving to be masters of ourselves; we also follow our ecstasies to the breaking point. Only through the slow accumulation of strength and wisdom does ecstasy become a possible expenditure—and only in the moment of ecstasy do we glimpse true mastery over the circumstances of our lives.

—This essay was inspired by Michel de Montaigne’s 14th essay, “That the taste of good and evil things depends on our opinion of them.”