You’re so bipolar. Stop acting crazy. Did someone forget their meds?

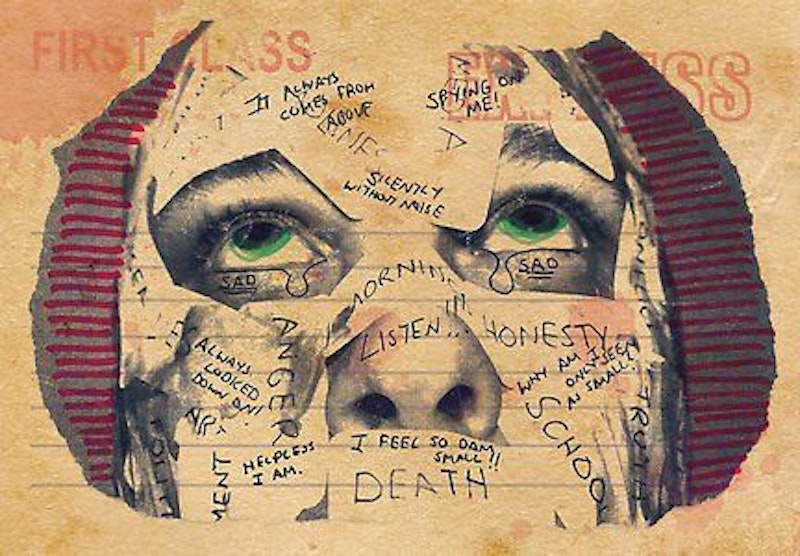

The list goes on. Comments like these are like calling something “gay” or “retarded.” Yet for some reason, describing an ex as “psychotic” or a light appetite as “anorexic” remains largely acceptable. The derogatory use of these words has helped perpetuate a mental health stigma.

In an article for The Atlantic, a woman describes having to keep her bipolar diagnosis a secret for fear of losing career opportunities or being perceived negatively at her job. Between taking her meds in the bathroom, going to see a psychiatrist during her lunch break, and grimacing as co-workers use her diagnosis as an insult; trying to hide her mental illness sounds like a fulltime job. Undoubtedly, many of the one in five Americans suffering from some form of mental illness face the challenge of “admitting” their secret, in part because it’s so often used as a punchline.

In grade school, it was difficult keeping up with the lies I told my friends about where I was during treatment for an eating disorder. Many of them, envious, would ask why it was I got to leave school so early. The excuses ranged from family visits to sick pets to impromptu vacations. I’d sit in the school bathroom during some lunch hours to avoid raised eyebrows and questions about my empty lunchbox. In seventh grade, “gay,” “retarded,” and any variation of “crazy” were all fair game. Girls would refer to fashion models as “anorexic,” and gossip about which classmates were “getting fat.” I can imagine how my friends who are now out of the closet felt when we used the word “lesbian” to describe ugly teachers.

There was one day in health class that mentioned eating disorders as a side note during a discussion about nutrition. No lessons about mental illness were taught until high school psych. Keeping it out of our vocabulary didn’t keep it from happening, and I knew several people who struggled with depression and eating disorder symptoms but were too scared to seek help.

There have been recent efforts by groups like Mindful Allies, which has inspired celebrities like Glenn Close to open up the conversation about mental illness. Singer Demi Lovato has spoken out about her own struggles with eating disorders, and recently did an empowering nude, no-makeup photoshoot for Vanity Fair. It’s promising to see Hollywood, which has long perpetuated the notion of “perfection,” moving toward body acceptance and advocating mental health awareness. Unfortunately, Hollywood can’t change the fact that 40 percent of those with serious mental illness do not receive treatment. Patrick W. Corrigan, author of Psychological Science in the Public Interest, points out that “The prejudice and discrimination of mental illness is as disabling as the illness itself.” Perhaps instead of asking people to “get back on their meds,” we should try a more sympathetic approach.

—Follow Sarah Grace McCarthy on Twitter: @birdy_grace