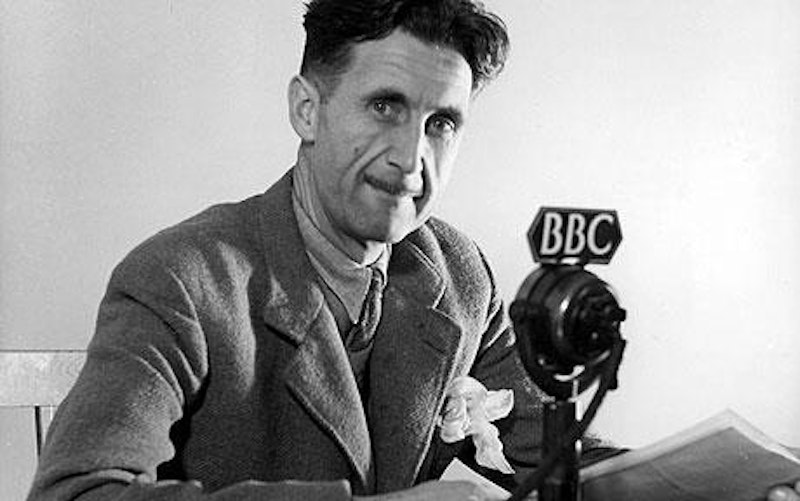

In his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language," George Orwell slammed political and literary classes for hiding behind grandiose and misleading language. Writers, Orwell argued, concealed the truth by using fancy words and long sentences that resulted in puffs of vague language instead of a clear and meaningful message. Politicians could hide unsavory truths by writing long sentences full of dazzling rhetoric instead of delivering a clear and useful conclusion. Orwell saw this as oppressive and as a tool of the powerful to disguise true intentions.

In this essay, Orwell mocked his contemporaries by offering fake "translations" of well-known passages into the "modern" English language he criticized. Perhaps his most amusing translation: (Ecclesiastes 9:11) I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

Here it is in "modern" English: Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account. Orwell concludes that in order to avoid butchering the English language in this way, writers must abide by a certain set of rules including, "never use a long word when a short one will do," "never use a figure of speech you are used to seeing in print," and "if possible to cut out a word, cut it out."

Nearly 70 years after Orwell's declaration, digital media has forced the political and journalist class into pithy, concise prose rather than the baffling rhetoric that Orwell so loathed and feared. In a world where the public consumes media in 140 characters or less, writers no longer have the freedom to shower readers with florid language or meaningless words. Digital media has created an environment where readers are a major flight risk. If someone becomes lost in a jungle of words, her or she will simply turn to any other of thousands of sources conveying the same story or an equally interesting message, with a single click. The public is no longer captive to a few and limited amount of paper-based media.

Such a state of rapid and picky consumption has resulted in a readership with the attention span of a toddler. Politicians and journalists must get to the point quickly and powerfully, or a reader will become disinterested.

This comes with many costs, and had Orwell still been alive today he may have criticized the current political and journalist classes for being as inauthentic as those he lambasted in 1946. Voices today often lack the space or time to adequately formulate or justify an argument, which squeezes out the thoughtful and authentic and favors either the politically savvy, or the obnoxious. The result is communication that is either predictable and machine-like, or boisterous and dogmatic. But the ghost of Orwell no longer needs to fear decadent language as a means for the powerful to deceive the public. Politicians will spar over Twitter and paragraph-long manifestos, with no room to hide. Each syllable needs to be carefully dissected, strategically placed, and never wasteful. All of which is in firm abidance with the rules laid forth by Orwell.