Right now, I am reading Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris. The novel is written in the first person plural, as if the Queen were narrating. This sort of experiment is usually a reason to be alarmed.

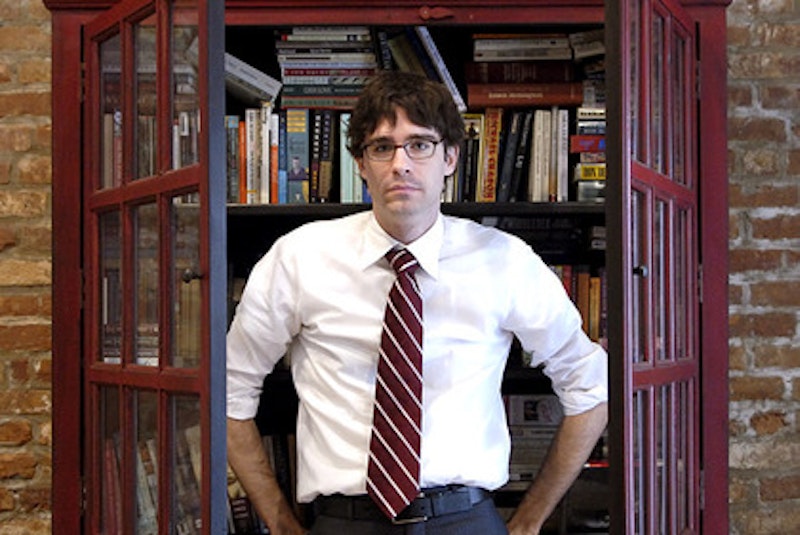

I was worried that the novel, like many of Chuck Palahniuk’s novels, would be all clever exposition and complicated technique; something to be read for its novelty, not for its literary content. At first, the conceit seemed precious. Actually, based on the back-cover photo of the author, I was prepared to hate the thing without reflection.

Joshua Ferris’ biographical snippet on the back cover of the new trade paperback edition of Then We Came to the End informs us that he lives in Brooklyn. And a quick reading of the entry about him in Wikipedia shows that he wasn’t born in Brooklyn – he moved there, joining the stream of the young and hip moving to Williamsburg or wherever to work in media, and to see and be seen. And most execrable of all, he holds an MFA in Creative Writing. I probably could have guessed Ferris was the product of a Creative Writing program without checking Wikipedia – the degree of correlation between authors who experiment with grammatical persons and authors who have MFAs in Creative Writings is, I would wager, statistically significant.

The picture makes it worse. I am sure that he is a decent guy, but Joshua Ferris looks like a tool – tweed jacket, thrift-store button-down, black-framed glasses. He looks like he ought to be sitting in the corner of a Humanities class conference, masturbating to the sound of his own voice, or else leading an indie pop band through a set of sloppy imitations of imitations of songs written by Colin Meloy. I was worried that the book would be an orgy of creative-class self-congratulation.

But it is actually a very good book. It deserves its critical acclaim, and I am glad that it seems to be selling briskly, even if it is supporting a hipster’s lifestyle. The feeling is what I imagine I might feel about buying a Ken Kesey novel in Kesey’s lifetime; the royalties will be spent objectionably, but the book is worth it anyway.

There aren’t a lot of novels written about office life. The last one I remember reading is Microserfs, by Douglas Coupland. In Microserfs, Coupland tells the story of a bunch of Microsoft employees who quit the company to form their own software-design company. The bulk of the plot centres on the romances and fights and insecurities of the characters. It is a very geeky book – actually, I didn’t feel entitled even to identify with the characters because I didn’t know what ASCII was, and didn’t know any programming languages. But it is also moving; the book captured the weird, intimate, and weirdly intimate way in which people relate to their coworkers and classmates.

Ferris captures the same mood – the strange way in which we get to know the people who are around us every day, either at school or at work. I am in class with dozens of people about whom I know nothing. I work at a bookstore with a bunch of people I know only in the context of vests and black shoes and endless customer service. I am friendly with these people – or most of them – but I don’t anything about them. There is a deep and fascinating gulf between our public and private lives.

Ferris captures this perfectly by shifting from the general – the use of ‘“we” as a way of illustrating what the advertising agency office-workers in the novel know about each other – to the specific. The first-person narrator swoops in on the individual secrets and lives of particular characters. The effect is gossipy, but is unexpectedly expressive and powerful. The move from the collective to the individual throws the characters into sharp focus and makes their individual joys and small tragedies seem large and important. The gossipy tone of the book is compelling in and of itself – gossip is addictive.

One of the first times I really recognized good writing was when I was compelled to read the short story “Araby,” by James Joyce, as part of a high school anthology of short fiction. I think for the first time I was able to recognize how the right timing and pace of sentences could take an ordinary event and make it seem momentous; before “Araby,” any fiction that wasn’t sci-fi or fantasy was boring to me.

I barely remember what the story is about, but I remember the way in which it made the embarrassment of early romantic love seem loud and painful. That control of the volume of emotion is a rare and powerful skill. Ferris isn’t Joyce, but he can make the friction between coworkers and work friends a source of genuine physical discomfort.

That shows a sensitivity worth appreciating.