It’s possible that nobody alive knows what’s in the last two paragraphs of “Miriam.” Truman Capote knew, since he wrote the story. His friend Barbara Lawrence knew: she read the story and suggested cutting the paragraphs. But this was long ago, when Capote was 20 and so young he wasn’t famous. Adolf Hitler and Franklin Roosevelt were still alive, though not for long. Looking at Gerald Clarke’s Capote: A Biography, we’re told of Lawrence’s idea and learn that she was features editor for Junior Bazaar. But the book doesn’t mention what the paragraphs said. Lawrence’s change does seem like a master stroke. “Miriam” now ends with three words and a few bits of punctuation, a scrap of text that stands against the white. What’s said in that brief line is shocking, and this shock takes the story from eerie to terrifying.

Capote later dismissed “Miriam” as a stunt, but the story made his name. “Short stories attracted more attention in those days than they do now—people talked about them the way they might discuss a hit movie or a best-selling novel today—and the reaction was almost instantaneous,” Capote’s biography tells us. The story put the young boy “where he had always wanted to be: in the center of the literary spotlight, admired, appreciated, and sought after.” Then “Miriam” lived on for decades in story anthologies, often ones with a slant toward horror and the supernatural.

But there’s something more to it than simple fear. Tennessee Williams thought so, anyway. “Miriam,” from the start of Capote’s career, and “Mojave,” close to that career’s finish, were the two works by his sometime friend that Williams praised above all the rest. Long before this, the literary scholar Newton Arvin wrote the young Capote to rhapsodize over “Miriam” and two other stories: “how real and yet how fantastically poetic they seem to me... there need be no end to what you can express for all of us of what it is to be human and afraid and in love and intensely happy.” Admittedly, Arvin’s own situation may have amplified his feelings, since at that time he was lover to the boy-genius. On the other hand, he wasn’t far off. Capote did find a limit to what he could do, but in “Miriam” we see how high that limit went.

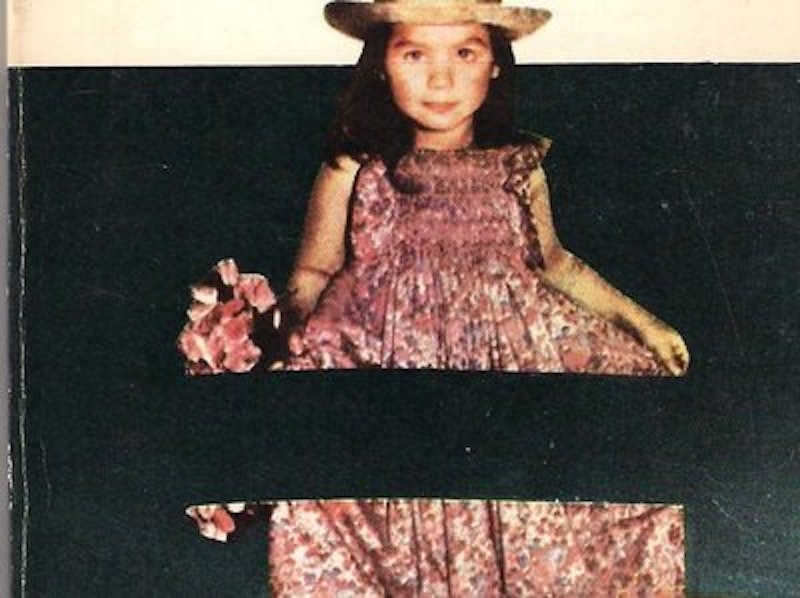

The action in “Miriam” is this: a lady living alone in New York is persecuted by a strange child, and eventually the child breaks her. This child is supernatural. She pops up at will and she looks like no ordinary nine-year-old (her hair is “absolutely silver-white, like an albino’s,” and we’re told it “flowed waist-length in smooth, loose lines”). The girl’s victim is Mrs. Miller, somebody dull and without nerve. By contrast the girl has style and plenty of nerve. Not only does she wear a “tailored plum-velvet coat,” she displays a “simple, special elegance” when she stands with her thumbs in her coat pockets. Her tormenting of Mrs. Miller takes the form of endless self-assertion. The girl doesn’t play mean, sly tricks. Instead she barges in on the poor woman, orders her around, messes with her things, and comments wanly on her taste.

Both the girl and her victim are named Miriam, which suggests that these different beings are somehow the same. Capote offered the thought that the girl was a vision brought on by schizophrenia. This explanation needs a little help (perhaps Mrs. Miller saw the velvet coat in a specially colored magazine illo), but one can’t help liking its no-nonsense approach. Capote’s biography makes heavy weather of the idea (“a supposedly rational woman succumbs to the terrors that lie hidden within her soul”). But it also makes heavy weather of the mystery, telling us that reader are left “with a tantalizing question: is Miriam real? is she supernatural?”

I’d say that little Miriam is many things, but she’s certainly death. Like much else in the story, this angle shows up in style choices, such as the dress the girl wears the second time Mrs. Miller sees her: “White silk. White silk in February.” Like many things in mid-century fiction, it also shows up in a character’s dream. After the girl has forced her way into Mrs. Miller’s apartment and humiliated her (she took the woman’s brooch!), Mrs. Miller dreams feverishly: “a small girl, wearing a bridal gown and a wreath of leaves, led a gray procession down a mountain path, and among them there was unusual silence till a woman at the rear asked, ‘Where is she taking us?’ ‘No one knows,’ said an old man marching in front. ‘But isn’t she pretty?’ volunteered a third voice. ‘Isn’t she like a frost flower... so shining and white?’” Where’s the supernatural white creature leading these gray folk? Into the ground, conceivably.

I suggest that the passage and story were written sideways, again a trait especially marked in mid-century fiction with its “show, not tell” literary chastity. In sideways fashion, the dream girl’s never identified, and especially not as Miriam, Mrs. Miller’s tormentor. In sideways fashion, we know of the girl’s special whiteness before hearing of it, since she has on a bridal gown. And, rather than seeing the child robed and crowned, we sense that she is: her dress and wreath and the procession add up to that effect. We also sense rather than see that the crowd is old. At the start we’re told the crowd is gray, a word that can mean old or dull or both. Everyone we hear is older than the child, since they’re adults; this difference slants our impression. Finally, “old” is the one adjective attached to anybody but the girl; the person after the old man is merely a voice. The crowd might be dull souls shuffling along, but it feels like the aged shuffling toward death.

We don’t have the story’s final paragraphs, but the first paragraph gives us plenty to work with, as tends to happen with well-made stories of the period. Mrs. Miller is 61 and she’s a widow. “Her interests were narrow, she had no friends to speak of, and she rarely journeyed farther than the corner grocery,” the story says. We’re also told that people don’t notice Mrs. Miller, that she dresses plainly and does her hair plainly, and that she seldom commits a spontaneous act. The three items in the last sentence make for a mirror image of Mrs. Miller’s tormentor, so the “terrors within” interpretation gains some force. But the passage as a whole has another angle. We’re told much—the passage is boldly explicit for a suave mid-century creature, with “narrow” announcing itself loudly—but what’s left out is the import. Mrs. Miller is starting old age, and she’s doing so alone because of the death of the person closest to her. There we have her situation’s unspoken essence. Then the brief, straightforward catalogue of her character and habits adds up to this unspoken judgment: she lives like someone getting ready to not exist. Her life is a rough draft for non-being.

This story about death takes place in white winter, a flamboyant winter conveyed by strings of Capote’s very fine description. What the “Miriam” winter does is muffle and isolate: “It snowed all week. Wheels and footsteps moved soundlessly on the street, as if the business of living continued secretly behind a pale but impenetrable curtain. In the falling quiet there was no sky or earth, only snow lifting in the wind, frosting the window glass, chilling the rooms, deadening and hushing the city.” The first time we see Mrs. Miller in action, as it were—that is, on her feet and doing something—she’s making her way through the snow and wind, “her head bowed, oblivious as a mole burrowing a blind path.” We’re offered this picture a little after hearing about her narrow ways and limited paths. Whiteness (the snow) and routine combine to round her down into something less than a person, and this reduced being is alone.

Aloneness goes with supernatural encounters. But in this case it’s also the heart of the encounter. The monster girl casually takes her victim’s brooch, and “it came to Mrs. Miller that there was no one to whom she might turn; she was alone, a fact that had not been among her thoughts for a long time. Its sheer emphasis was stunning. But here in her own room in the hushed snow-city were evidences she could not ignore or, she knew with startling clarity, resist.” This aloneness—it’s never presented emotionally, as loneliness—highlights the story’s moment of peak menace and runs through the rest of “Miriam.”

Three times, and three times only, we see Mrs. Miller with fellow human beings. There’s a by-the-way mention of a conversation (“she ate breakfast and chatted happily with the waitress”), there’s a mysterious crossing of paths with a shabby old man, and there’s the story’s climax, where Mrs. Miller bangs on her neighbors’ door for help. No doubt the man is the one mentioned soon after by the little girl: “The last place I lived was with an old man; he was terribly poor and we never had good things to eat.” This being and Mrs. Miller are trapped by a bond that somehow leaves them separate: “Suddenly she realized they were exchanging a smile: there was nothing friendly about this smile, it was merely two cold flickers of recognition. But she was certain she had never seen him before.”

A little later: “She hurried inside and watched through the glass door as the old man passed; he kept his eyes straight and ahead and didn’t slow his pace, but he did one strange, telling thing: he tipped his cap.” The old man may also be the old man in the dream, though I hope not. What strikes me is the refracted, disassembled way the basics of social contact show up here. The two characters smile but feel no friendliness. They recognize each other but don’t know each other. The man tips his cap while pretending she isn’t there.

Finally, Mrs. Miller has her one fully presented conversation with her own kind. These are her neighbors, the people she goes to for help. Their voices shatter the story’s hush: “‘Anything wrong, lover?’ asked a young woman who appeared from the kitchen, drying her hands.” Daylight comes back on for a while, or the comfortable electric light of daily life in the city. Mrs. Miller is among the living. Then she’s cast out from them. The young woman’s fellow goes upstairs to Mrs. Miller’s apartment and finds no monster child or any sign of its presence. The young woman, “as if delivering a verdict,” says, “Well, for cryinoutloud.”

The verdict, apparently, is that Mrs. Miller is too deluded to be bothered with, which seems harsh but may suit the period being described. In any case, the old lady is sent back to her apartment, there to await her fate and the story’s final two paragraphs. She sits in a room where everything is “lifeless and petrified as a funeral parlor,” and where everything blurs on its way out of existence: “The room was losing shape; it was dark and getting darker and there was nothing to be done about it; she could not lift her hand to light a lamp.” She and everything are running down and folding up and getting ready to be nothing. Then she rallies. Then there’s the shock, and we never find out what comes after.

My guess is that the final paragraphs contained more whiteness (we know the girl’s still wearing her silk dress) and more blur and more hush; boundaries collapse and the woman’s identity fades into the dimness as the girl overwhelms her. Alone, the woman finally vanishes. This is death, specifically the death that comes with living into old age. People thin out, you’re alone, and then you’re gone. And first you thin out too. Your life becomes less even as you’re living it.

I don’t claim there’s any particular reason to attach this aspect of death to a pushy young girl with ideas about decor. I only say the combination works, and that the experience being evoked is what infiltrates the story with the “fantastically poetic” sense of “what it is to be human” that set Newton Arvin thrilling. Capote could’ve produced a spook story with modish trimmings, a magazine entertainment (published in Mademoiselle’s June 1945 issue) for young people who derived some pepper from seeing age bullied by a child. Instead he produced a story that haunts us with one of life’s subliminal, inevitable, grim shortcomings. If the story is forgotten now, it shouldn’t be.