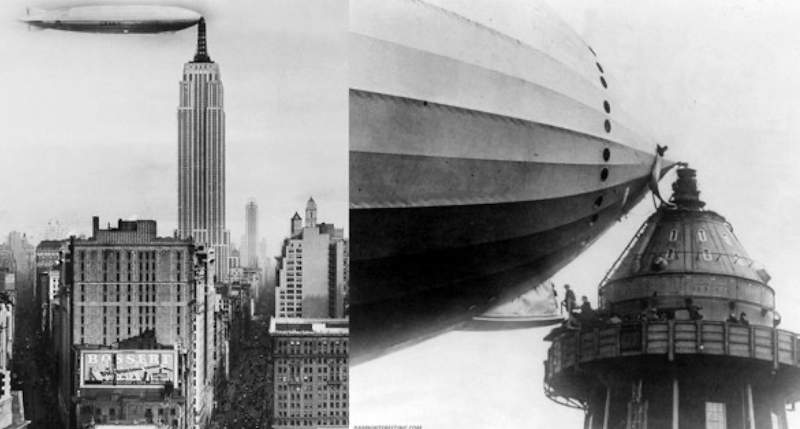

In 1931, the promoters of the Empire State Building intended to open its uppermost 16 stories—the stainless steel, wing-adorned finial—as a mooring mast. Dirigibles, rigid-framed lighter-than-airships up to two-thirds the size of the building itself, “sustained in the sky by the lift of gases lighter than air,” would dock and embark or disembark passengers at the 102nd story. Lounges, ticket agencies, and baggage rooms were on the 86th floor. Airships were considered better suited to long-range aerial travel than airplanes.

The U.S. Navy’s dirigible crews at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, 60 miles south, might’ve told them mast-docking was hard enough when a ground crew restrains the airship with ropes. Docking an airship half the size of the Empire State Building at a mast swept by unpredictable winds 1000 feet above the city seems insane. Only one blimp—a streamlined non-rigid gasbag with stabilizers and rudder at the rear and a gondola, or control car, suspended below—ever made contact with the mast, on September 16, 1931. The airport never sold a single ticket. The mooring mast and lounges became the observation decks.

New Yorkers had watched balloonists for over a century by 1931. On September 9, 1830, 30,000 people watched Charles Durant cast off from Battery Park in a hot air balloon. They were fond of these stunts, and stunts are all they were, because hot air balloonists remained at the mercy of the uncharted winds and unpredictable weather.

In 1899, Ferdinand, Count Zeppelin devised the first dirigible. Although blimps are safe and reliable within their limits, those include a length no greater than 360 feet, which restricts their payload and endurance: a gas bag any larger flexes under stress and becomes ungovernable. The dirigible, being a cluster of individual gasbags, or cells, enclosed within a cigar-shaped framework, covered with doped cotton fabric, has no flex problem. The airship can be much bigger, with more engines and greater payload.

In 1919, when the experimental airship program of the U.S. Navy began, American industry had never built a dirigible. Therefore, the Navy ordered one from the British government. Cmdr. C.I.R. Campbell, who designed and constructed the ZR-2 (it didn’t last long enough to be named), was a naval architect without aeronautical experience. Later, an American investigator, after reviewing Campbell’s notebooks, realized Campbell hadn’t known how to calculate aerodynamic stresses—the loads imposed by the pressure of air when an airship is driven by its engines, which increase as the square of the speed—and had simply guessed it. This had an unhappy result. On August 23, 1921, the ZR-2 was over Hull on her fourth test flight when, according to the court of inquiry, her commander ordered the helmsman to turn the helm from mid-left to hard-right. Before thousands of eyewitnesses, the airship buckled from the stress of turning under its own power on a calm day and fell burning into the River Humber.

The Navy had established its first airship base at Lakehurst in February 1919. Then, the Navy began building the first American-made airship. Slender, cigar-shaped, her duraluminum framework covered with aluminum-painted doped cotton fabric, ZR-1 was 680 feet long—say, a little over 2 ½ midtown blocks. Her range was 5000 miles. Six Packard 300 horsepower engines propelled her at 65 knots. Unlike ZR-2 and the German zeppelins, ZR-1 remained aloft with helium rather than inflammable hydrogen. The ship’s bridge crew worked in a control car suspended forward below the hull; the single keel, roughly 15 feet wide, was the ship’s main street, containing galleys, water closets, the officers’ and crew’s berths, and fuel, water, and ballast tanks.

On September 7, 1923, three days after her first flight, a ground crew of 320 sailors and Marines walked ZR-1 out of Hangar No. 1 at Lakehurst. Her executive officer, having completed the checklist, turned to her commanding officer, Cmdr. Frank McCrary, USN, to formally request permission to take her up. “Permission granted,” McCrary replied. The XO, his head and shoulders framed by the port window, leaned out and roared the command, “Up ship!”

The ground crews released the lines, and ZR-1 began rising. At about 1000 feet, her motors kicked in, with “a distinct mellow boom comparable to the whistle of a large steamer.” She climbed to 7000 feet to test her automatic gas valves (helium expands as the ship gains altitude; ZR-1’s automatic valves blew off gas at an altitude of 6000 feet to prevent the gas cells from rupturing) and testing her control surfaces—the stabilizers, elevators, and rudder.

Around 10:00 a.m., she set off for New York. McCrary had promised she’d be over New York at 11:30 a.m. Around 11:20 a.m., she sailed over Todt Hill, Staten Island, and, engines thundering, the Stars and Stripes snapping in the wind, ZR-1 charged up the Bay at 1600 feet, passing the Statue of Liberty and Governor’s Island, dwarfing the three Army DeHavilland biplanes sent up to greet her. Steamers sounded their whistles in welcome; coastal batteries boomed out salutes; the silvery airship returned down the East River. Tens of thousands filled the streets to see her. The flyby was a sensation, even a triumph: no one had ever seen anything like her outside the newsreels, and even The New York Times covered it.

ZR-1 was innately dramatic: she was huge, then the largest aircraft to fly over Manhattan. She was also loud: an eyewitness later wrote of the “deep, muttering vibration of air,” of “sound unlike any other: sound I could feel; it poured from the sky, wave after wave… the deep throbbing grew louder and louder… It grew and grew… swelling and roaring with incredible power as it came on and on...”

All that remained was to give her a name. On September 24, 1923, Marion Thurber Denby, wife of Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby, walked into Hangar No. 1 at Lakehurst. ZR-1 floated lightly above her cradle—quiescent, but fully alive. Mrs. Denby christened her Shenandoah, which, she said, means “Daughter of the Stars.”

In February 1924, Lt. Comdr. Zachary Lansdowne relieved McCrary as commanding officer. Trained in British airships during World War I, Lansdowne had more flight time than any other naval officer; he was also a skillful ship handler and a fine leader, who inspired loyalty and devotion among his subordinates. Under Lansdowne, she was thought a lucky ship.

On September 2, 1925, Shenandoah set off on a tour of the Middle West. She was aloft at 2:52 p.m., over Philadelphia by 4:00 p.m., and over Wheeling, West Virginia, by 1:45 a.m. on September 3. Around 2:30 a.m., the navigating watch officer, Lt. Lewis Hancock, observing lightning flashing to the north and west, called Lansdowne to the bridge. Shenandoah was then over Cambridge, OH, heading west by southwest. At 4:00 a.m., Hancock was relieved by Lt. Charles Rosendahl; concerned by the weather, Hancock remained on the bridge to aid the captain.

At 4:20, Rosendahl noted, she was making 38-40 knots at about 1700 feet. Then, at 4:23, she entered an updraft and began rising at 200 feet per minute. No one in the ship’s company had experienced this before; as Rosendahl later learned, no one in the world had. Lansdowne ordered her elevators put down and engines set to full power. Her ascent remained unchecked for six minutes. When she leveled off at 3100 feet at 4:30, she couldn’t descend, and pitched and rolled in the turbulent air. Engine No. 2 overheated and failed at 4:34.

Then she entered another updraft, moving at 2100 feet per minute. As she rose past 6000 feet, the automatic valves began releasing helium. Lansdowne, knowing she was rising faster than the valves could safely release the expanding helium, ordered her main valves opened. Even so, she continued rising. Engine No. 1 failed at 4:46. She rose to 6060 feet before hitting a cold air mass at 4:47, and began descending at 1500 feet per minute. Now Lansdowne had to drop ballast to slow her fall. At 4:48, she struck yet another updraft and began rising yet again.

Through all this, Lansdowne remained perfectly calm and the bridge crew continued working as calmly and efficiently as in normal flight. The commanding officer, knowing Shenandoah had lost nearly 10,000 pounds of lift with the released helium, having only 2500 pounds of ballast left, ordered the keel watch to stand by to drop fuel tanks as the only way to save the ship in another descent. He ordered Rosendahl up into the ship to see they were ready to drop fuel. Later, Rosendahl remembered, “The ship took a very sudden upward inclination.” A violent gust of wind struck the underside of the bow, forcing it violently upward. It was as if she were being twisted in two directions at once. She rolled to port. Engine No. 4 broke from its attachments and swung down beneath the hull. At 4:52, over Caldwell, Ohio, her frame gave way and she broke in two.

For about 90 seconds, the rudder and elevator cables held the two halves of the ship together. Then the tail began sinking, pulling the control car by the cables. The strain snapped the car’s suspension wires, one by one. Then the end links of the chains holding it to the hull opened and the control car fell away, throwing Lansdowne and his bridge crew into the sky. The altimeter readings have been charted, showing the ship tossed up and down as Lansdowne fought for her survival, until a sudden break records where Shenandoah was overcome. At the end of the chart is a long, jagged, downward line, recording the altimeter’s final plummet through the Ohio night.

Yet, 29 men survived. The tail section fell slowly, the remaining gasbags easing its descent, and came safely to earth with some 20 men. The other fragment, some 210 feet long, first soared to 10,000 feet. Rosendahl, clinging to the wreckage, realized they had a chance. There was 1600 pounds of ballast and the fuel tanks Lansdowne had ordered jettisoned, and the valves on the surviving gas cells still worked. He could maneuver the fragment: he could free the balloon to a landing.

Rosendahl assigned men to ballast bags and valves. He ordered the trail ropes—the lines held by ground crews to restrain the ship—dropped. Then he crawled to the open end of the nose, where the ship had torn apart, to see where he was going, and began giving orders. Around 5:45 a.m., while passing over farmland near Sharon, Ohio, Rosendahl saw Ernest Nichols, a farmer, already at work. Apparently, Nichols hadn’t noticed a 210-foot long flying object dragging ropes through his fields. Rosendahl shouted, “Grab the ropes.” Nichols looked up in astonishment, and then, to his credit, he grabbed a trail rope and snubbed it around two tree stumps. Then the crewmen jumped down.

By 7:00 a.m., Rosendahl, now the senior officer, had listed the dead, injured, and survivors. The 14 crushed bodies had been recovered. Then he telegraphed Lakehurst, while the dead were embalmed and placed in coffins marked “not to be opened.” Rosendahl later received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions on September 5, 1925.

Caldwell, the nearest town, was having a county fair. The yokels descended on the crash site, “providing in the hot, dusty sunlight a Roman holiday atmosphere the survivors long remembered with loathing.” They stripped the tail section of most of its fabric, equipment, logbooks, and instruments. They broke into the dead crewmen's lockers for souvenirs.

Nearly a century later, the crash of Shenandoah is the greatest event that ever happened in Noble County, Ohio. The locals have even set up a picnic ground where the control car and its crew fell to earth, on a farm east of Route I-77. To this day, framed pieces of Shenandoah’s envelope and other memorabilia, including, one assumes, the personal property of her dead crewmen, are treasured at regional farm auctions and flea markets.

A witness later testified at the court of inquiry, “No European designer could possibly imagine the violence of weather conditions in the American Middle West.” The court found no negligence or culpability.

The experimental airship program continued for another 11 years. The U.S.S. Los Angeles, the only American dirigible built at the Zeppelin Works, had the second-longest career of any dirigible in the world, remaining in service from 1924 to 1932 as a scout, flying aircraft carrier, and test platform. From 1926 to 1926, Rosendahl served her as executive officer and then commander. Los Angeles was decommissioned as an economy measure, and then re-commissioned in 1935. In 1939, she was finally moored in hew hangar at Lakehurst, struck from the Navy list, and dismantled. She was a good ship, the only Navy dirigible that didn’t fail.

In 1928, the Navy contracted for two new dirigibles: U.S.S. Akron and U.S.S. Macon. They were immense: 785 feet long, roughly 2½ times as long as a Boeing 747. They were the culmination of the American experience with dirigibles, the learning accumulated through working with Los Angeles and the loss of Shenandoah. Neither survived two years in service.

Akron first flew on September 23, 1931. Rosendahl commanded her for eight months in 1931-32, testing her for use as an aircraft carrier. On April 3, 1933, she departed Lakehurst on a routine training flight around 7:28 p.m., encountered an unexpected and violent thunderstorm, and, carried down by low-pressure turbulence, smashed into the sea off Barnegat Light, New Jersey around 12:15 a.m. Three men survived of a crew of 76.

Macon was launched on April 21, 1933. On February 12, 1935, Macon was off Point Sur, California on a training exercise when a crosswind shattered her upper fins. Within minutes, she was in the water. President Roosevelt ordered the dirigible program discontinued. When the Zeppelin Hindenburg burst into flame, crashed, and burned while mooring at Lakehurst on May 3, 1937, Cmdr. Rosendahl, then station commander at Lakehurst, led the firefighting and rescue efforts.

The Hindenburg disaster ended the dirigible era.

On September 6, 1942, Rosendahl took command of the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Minneapolis. Two Japanese torpedoes blew off 80 feet of her bow and disabled three of her four boilers. Rosendahl and his crew kept Minneapolis afloat and, on one engine, sailed some 33 miles to Tulagi through “skillful damage control work and seamanship.” Her crew jury-rigged a temporary bow out of cocoanut logs purchased from the locals and brought her to Pearl Harbor. Captain Rosendahl received the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second-highest honor for extraordinary heroism in combat.

Vice Admiral Rosendahl retired in 1946 and died in 1977.