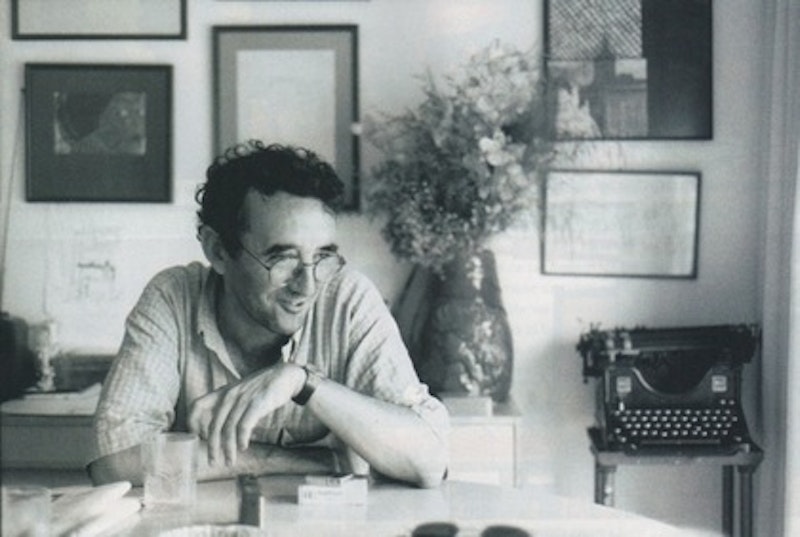

Roberto Bolaño was already deceased by the time his oeuvre reached English-reading audiences—first as a steady trickle of novellas from New Directions press that later grew to a great critical-commercial watershed with the translation of his award-winning book The Savage Detectives last spring—and as such, he came to American readers with a pre-packaged myth. Born in Chile in 1953, Bolaño lived a quintessentially literary-romantic life: globetrotting throughout Europe, Mexico, and South America; founding a youthful school of poetry called the “infrarealist” movement; drinking and taking drugs to such an extent that he apparently left teeth behind in every place he stayed; turning to fiction writing out of financial necessity (seriously) once he had children; and completing the slew of prose that constitutes his most enduring work under the specter of death, during a period of declining health that led to his eventual expiration from liver failure in 2003.*

The bio—Beats-style hard living and travel mixed with a Keats-style race against fate—makes for sexy lede copy, yes, but it also helps explain the unprecedented level of histrionic, effusive, gushing praise that has been piled on the most recent Bolaño translation, that of his posthumous 900-page enormo-novel 2666. In its themes, historical scope, characters, and ambition, 2666—which he purportedly put off cancer surgery to finish—certainly represents some kind of ultimate artistic statement on Bolaño’s part; but this self-styled masterpiece is also a frequently miserable reading experience, its occasional patches of beauty and insight crippled by its author’s juvenile and unforgivably nihilistic worldview. It’s hard to imagine another book this long and learned that nevertheless says so little about the world; equally difficult to think of a book that so romanticizes the literary life while systematically denying its readers even the slightest customary dividends that fiction affords—narrative, stylistic, moral, or otherwise. 2666 is often fascinating and occasionally exhilarating in the breathless manner of the superior Savage Detectives, but the chorus of decidedly un-critical hosannas feels more like the outcome of publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux’s marketing muscle than any serious intellectual consideration of Bolaño’s work itself. (More raves available here, here, here, and here.)

2666 comprises five sections, ranging from 60 pages to almost 300, that were initially to be published as separate books but have now been bound together, which is appropriate as they share motifs, settings, and characters. All are ostensibly about different protagonists and are written with very minor stylistic variations, but it’s slightly misleading to read this as a five-part novel. 2666 actually resembles The Savage Detectives’ three-part form, which introduced its poet protagonists through a hanger-on’s journal entries in Part 1, waded through an extended middle section concerning events that followed the protagonists’ disappearance, and then resumed the journal in Part 3 to explain the mystifying truth. Here, Bolaño’s bookends are similarly literary—parts 1 and 5 concern the fictional German novelist Benno von Archimboldi—while the greater middle of 2666 lowers us into another elliptical detective story, here concerning hundreds of unsolved murders in a fictionalized Ciudad Juarez called Santa Teresa. The novel’s underlying tension is the implication that this writer's work and life somehow relate to the ongoing tragedy in the Sonora Desert, but by the time Bolaño gets there, in the final 15 pages, even this puzzle’s explanation has been made to seem small; the relationship between the two storylines explains everything and answers nothing, which is the only proper ending for a book so riddled with references to disappearance, oblivion, and nothingness.

Bolaño’s style is terse and arid, almost devoid of adjectives and direct access to his characters’ emotions. It’s a style reminiscent of Borges’ Universal History of Iniquity, an obvious influence that itself mimics sub-literary fare like detective novels and police reports. When Bolaño indulges his pure storytelling powers, his writing reaches an incredible pitch that feels simultaneously effortless, insinuative, and frightening—it’s a given that none of his stories end well. In those moments, he is the rare “literary” writer whose work breezes by. 2666’s first part, “The Part About the Critics,” freely dispatches this gift, resulting in some of my favorite Bolaño writing. Four pan-European critics—three men and one woman from France, Italy, Spain, and England, respectively—are introduced as they individually discover Archimboldi’s work, and they soon build a comradeship from occasional meetings at German literature conferences. The English woman finds herself in a love triangle between the Frenchman and Spanish scholar, and their cautious, confusing non-romance is so engrossing, to us and to them, that the true story is resigned to the background—thanks to their academic efforts, Archimboldi goes from cult unknown to perennial Nobel candidate. Bolaño’s characters are almost always writers, but in this section he most perfectly accentuates the simultaneous heroism and futility of writing itself—the way a novelist can consume a person’s entire intellectual and professional life yet remain secondary to that person’s own piddling romantic drama.

The scholars are eventually drawn to Santa Teresa on a hunch from Archimboldi’s publisher that the reclusive writer is living in the town. They don’t find him, naturally, but they all reach a certain state of forlorn grace by the section’s end; the bond they share over Archimboldi’s work (which, tellingly, we only experience by way of their reactions and passions) stands as the greatest possible intimacy after their various couplings fail. But from here, Bolaño stays focused on Santa Teresa even as the critics presumably leave. The next three sections, a total of 500 pages, examine the town’s murder spree from the point of view of a local professor and father, a visiting New York journalist, and the police. These are dark pages, unrelentingly so, with only a few novelistic crumbs sprinkled along the way (recurring metaphorical motifs, judicious foreshadowing, the sudden unearthing of seemingly helpful clues) between scenes of brutal violence and encroaching madness.

Parts 2 and 3, regarding the professor and journalist, are both so slight that it’s a wonder Bolaño didn’t simply incorporate them into the titanic Part 4, which itself contains innumerable separate plots and characters. A few of these, like an elderly seer named Florita Almada and a church desecrator nicknamed The Penitent, provide some of 2666’s most stirring passages and exhibit Bolaño’s gift for economical character sketches. But they’re made insignificant, no doubt intentionally, by the unflagging body count. On and on Bolaño goes, giving a grisly coroner’s-eye-view of Santa Teresa from 1993 through 1996, the phrase “anally and vaginally raped” popping up throughout like the chorus of a folk song. At one point a number of women in a row have their nipples bitten off; at others, the killings stop for months at a time, only to resume again with unchanged ferocity.

The combined effect of “The Part About the Crimes” is certainly bludgeoning, as many critics have noted, but it’s also often boring or, worse still, perverse. The rash of unsolved sex crimes and murders has a real-life precedent in mid-90s Juarez, but Bolaño stampedes over the metaphorical potential of this gruesome desert in favor of literalization. The most damning and relevant aspects of these crimes are the perceived mishandling of the investigations by the police; the horrifying nature of each individual attack does nothing to enhance our understanding of the event or its societal implications. What does Bolaño achieve by guiding us through hundreds of blood-soaked crime scenes and violated orifices that he wouldn’t achieve by guiding us through 10, or five, or two? What's worse, Bolaño even acknowledges as much in Part 1, when the Spanish and French scholars express amazement over "the way Archimboldi depicted pain and shame": "Delicately." If only Bolaño's readers were allowed the same experience.

When we read this parade of atrocity, particularly in light of the other moments in 2666 when women are raped or otherwise forcibly used for sex, it’s hard not to imagine that Bolaño took some small level of skewed enjoyment from the project. Even in his more romantic (or at least consensual) sex scenes, the people involved always “fuck until the sun comes up” or some variation on the phrase. Sex is an altercation, in other words, and orgasms are always full of pressure release but never emotional catharsis. This is of a piece with Bolaño’s general worldview, which, particularly in 2666, is so bleak that it seems disingenuous coming from a man of his obvious intellectual curiosity. Periodically during Part 4, one character or another will assert, for instance, that, “the secret of the world is hidden in” the Santa Teresa killings, or that hardscrabble, politically bankrupt Mexico somehow resembles a microcosm of the contemporary world. Bolaño of course leaves these assertions unchallenged and unspecified, as is the wont of an artist this obsessed with obtuseness and pointlessness. But if such an artist expects his audience to wade through this amount of unrelenting horror and despair, the audience should be made to feel that such a journey is morally useful or instructive, and Bolaño offers no such comfort.

In 2666, all aspects of contemporary existence lead inexorably into the void. The scholars end Part 1 emotionally unrequited and no closer to finding their hero. Amalfitano, the professor in Part 2, goes slowly insane. Charles Fate, the journalist in Part 3, is led into a lower level of the Santa Teresa inferno that only expands our knowledge of the urban underbelly’s scale without illuminating how our why such an immoral morass forms in the first place. Part 4 is essentially a series of dead leads, false arrests, and unflinching brutality. Even Part 5, where Bolaño reveals the link in the chain connecting his stories, is a red herring, and contains no real closure or explanation of the violence. Along the way, minor characters fight their own pointless battles for artistic relevance or personal connection or emotional understanding, and all are unceremoniously denied their pursuits.

Such blanket discontent is Bolaño’s prerogative, but his ultimate explanation for the world’s meaninglessness is juvenile. The majority of the killed women are workers in Santa Teresa’s many maquiladoras—the assembly factories where western manufacturers exploit cheap workers and loose labor laws—so Bolaño invites us to see these killings as some kind of capitalist endgame. Thus Charles Fate enters a McDonald’s-esque restaurant in Santa Teresa and observes, “This place is like hell.” Or an investigator realizes that the strict timing of maquiladora shifts might make it easy for the killer to target specific girls by memorizing their schedules. Later, a different investigator discovers that the majority of victims are workers, not whores as he originally suspected, and “as if a lightbulb had gone on over his head, he glimpse[s] an aspect of the situation that until now he’d overlooked.” And even this minor, silly point is undermined for the benefit of greater nihilism: “It’s fucked up, that’s the only explanation,” yet another inspector intones later on, and Bolaño gives him the final word before the according section break.

It’s inevitable and perhaps even fitting that a book of this scope and moral darkness would ennoble an underground following—2666 also abounds with cult-friendly references to the greater Bolañoverse, including the continuation of themes and styles from his earlier work like Nazi Literature in the Americas, cameos from his other books’ characters, and the title itself, which is implicitly the same vague apocalyptic date alluded to at the end of The Savage Detectives, here given a hip semi-Satanic twist. But it’s inexplicable how such a book has become the literary sensation of the season. (The author would have perhaps agreed; Archimboldi says in Part 5, “Everything that ended in fame and everything that issued from fame was inevtiably diminished... Fame and literature were irreconcilable enemies.”) Not to belittle Bolaño, whose writing is clearly the outcome of serious thought and artistic intensity, but it’s odd to see such a grim book be greeted with this level of unabashed journalistic adoration. It seems impossible to me that any reader could finish 2666 and recommend it unreservedly as so many critics have done, mainly because it feels, unlike The Savage Detectives or Bolaño’s shorter work like the fascinating By Night In Chile, so contemptuous of its audience. Those books are shocking and dark in their own ways, as well, but they allow a certain amount of joy and complexity to seep through, if only through their impressive stylistic reach. 2666, meanwhile, is a singular work, but a thoroughly, purposefully unrewarding one. I admire the persistence of Bolaño’s vision in it, but I find that vision ridiculous, reminiscent the younger self that Thomas Pynchon rejected in the preface to Slow Learner: “A pose I found congenial in those days—fairly common, I hope, among pre-adults—was that of a somber glee at any idea of mass destruction or decline.”

It’s that pervasive contempt that makes 2666 so disappointing and sad. If Bolaño actually viewed the world this way, it’s tragic to envision this man, slowly dying from cancer, his faith in humanity ossified beyond repair; if he instead somehow falsely felt that his grandest artistic effort required such bleakness, it’s unfortunate to think of such a gifted man sacrificing his work’s natural effortlessness to make such a hollow statement on our world. I can’t help but think that, were our country’s literary critics paying less attention to Bolaño’s marketing buzz and more attention to the book itself, they wouldn’t be able to muster the strength for such sensational praise.

2666 by Roberto Bolaño. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 898 pp., $30.

Also recently available: The Romantic Dogs: Poems by Roberto Bolaño. New Directions Press, 143pp., $15.95.

*[UPDATE: This paragraph originally stated that Bolaño died of lung cancer. He in fact never had the disease, and died from complication due to liver failure, as the change reflects.]