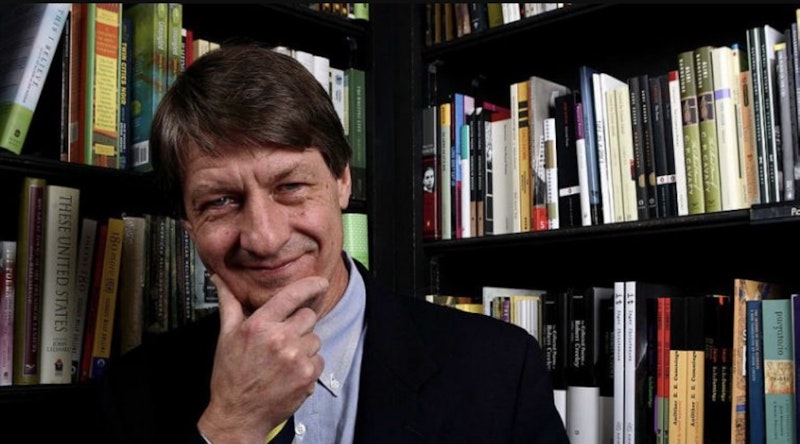

I first learned of P.J. O’Rourke, who passed away last week, from leftists protesting in advance of a speech he was to give at Brown University, where they’d posted passages from his essays about troubled foreign lands, insightful but filled with callous slang and broad ethnic generalizations. Each passage was topped with the activists’ question “Is this funny?” Unfortunately for the activists, the passages—mostly from O’Rourke’s book Holidays in Hell—were hilarious and served as inadvertent advertising.

I went to his speech, which was humble and cautious, filled with the sorts of semi-apologetic contextual explanations that many on the right now advise never, never giving to a leftist audience, lest you encourage them. But by today’s standards, the audience was fairly smart and attentive, and things went pretty well. After that, I took some of my inspiration as one of the campus libertarian humor writers from O’Rourke, which led to an apt face-to-face encounter with him several years later.

During my first few years of writing professionally about libertarian issues, I thought I should seize an opportunity to visit free-market Hong Kong in 1997 during the week of its transfer back to control by the Communist government in Beijing—a trip arranged via the Claremont Institute, nowadays associated more with populism than libertarianism, though a young Michael Anton was part of the travel group back then, two decades before he became famous for his populist argument that Trump must seize control of the government like passengers revolting against airplane hijackers.

I found myself in the Foreign Correspondents Club bar of Hong Kong, and the Marxist New York Times photographer with whom I’d agreed to meet up was late. You had to be a club member to buy a drink, though, so I was stuck just standing around—until I spotted one stranger in the crowd who I recognized: P.J. O’Rourke. Asking a famous stranger to buy you a drink (without sexual overtones) would be absurd in most cases, but O’Rourke was very understanding about such things, especially under strange circumstances in distant lands. So, I mooched a drink and got to hear some stories about him turkey-hunting in knee breeches in New Hampshire until the Marxist arrived.

The Marxist, in a reminder that very different policy valences prevailed just a few decades ago, explained that one of the few things about Hong Kong law he admired was their resistance to immigration, since he didn’t think small islands should be letting people in willy-nilly. He thought we should be grateful if regulations such as rent control back home in Manhattan were having the unintended effect of dissuading newcomers from settling there, since Manhattan was too crowded. I haven’t kept in touch with him but imagine he’s somewhat pleased by the recent exodus of Manhattanites seeking lower prices and masklessness in red states.

Less surprising to me than the Marxist’s dislike of immigration (or Anton’s conviction that apparent logical contradictions in ancient writings must be deliberate Straussian-style messages for the elite, which another member of our travel group, who’d go on to work for the Trump administration, wisely argued might simply be a side effect of the ancients writing without the easy deletion and cut-and-paste functions of modern word processors) was O’Rourke’s easy straddling of the divide between conservative cynicism and libertarian humor.

National Lampoon, for which he had written before moving on to more serious political venues, had given the world the movie Animal House, after all, and what is Animal House if not a treatise on the ways that a local, fraternal tradition of rebellion can be a bulwark against coldly dispassionate official tyranny? Whether Delta House is violating its housing contract and whether Dean Wormer is a government-funded official or just a private-sector jerk is a secondary question; whether my fellow libertarians or any other sort of ideologues want to hear that. On a more fundamental level, as I’ve written before, you know Wormer is an authoritarian who deserves to face resistance, which is the main point.

Comedy, despite what the recent new generation of humorless critics has told you, should always have some element of resistance and irreverence about it, whether the thing being resisted is government, religion, the stuffy corporate boardroom, racism, anti-racism, or just humorlessness itself. I think philosopher Daniel Dennett has correctly identified a defining aspect of humor that makes it a natural ally of both rebellion and the somewhat conservative correction of error: Humor tends to draw our attention to jarring errors in logical framing. You think you’re dealing with a question about a chicken’s emotional state and then you abruptly realize you’re just facing a question about the chicken’s physical location. It’s an educational opportunity to admit you made some implicit, false assumptions. And so you grow mentally—if fuddy-duddies don’t put a stop to the whole process.

Far from being safe and polite, comedy, like philosophy and sci-fi, gives us opportunities to ask dangerous, provocative questions at low cost, and that’s good. I notice Matt Yglesias in the past few days lamenting the decline in jokes about contrarian “Slate pitches,” and I see a writer who defends sex workers online fending off criticism because she leans toward defending Prince Andrew against the formerly slightly-underage woman who recently sued him for having sex with her a couple of decades ago.

I’m not sympathetic to the Prince, but as an admirer of philosophy, debate, and comedy, I find myself grateful that someone’s willing to take up a very unpopular side of the argument on that issue (whereas the Prince himself left the arguments to his lawyers). In fact, I can’t help but think of some comedic lines that might help to underscore the suppressed complexity of an issue like that.

For instance: If Stranger Things season 4 airs in 2022 when Millie Bobby Brown is 18 but was shot a couple of years earlier when she was only 16, is it wrong to masturbate while watching the show? (You see how I slightly defied your expectations about where that question was going.) Furthermore, Brown turning 18 means some enterprising porn producer could now legally hire her and Jeri Ryan (54) to do a lesbian parody film in which they play their best-known roles and call it 7/11. Hey, don’t complain to me. They give Paul Thomas Anderson awards for films inspired by these sorts of ideas.

More importantly, as Straussians like the aforementioned Anton well know, comedy is sometimes the subversive or philosopher’s best defense against a humorless censorship regime that can’t quite figure out whether he’s violated the rules and thus can’t quite justify cracking down.

If, say, we one day learn that there was something criminally fishy about that recent fatal blow to the back of comedian Bob Saget’s head and that it was confirmation of years of conspiracy theories about a regime of dangerous Hollywood molesters abusing his co-stars the Olsen twins, we might look back with gratitude upon Gilbert Gottfried for offering us a comedic formula for discussing such things when he repeatedly yelled at a celebrity roast years ago that “Bob Saget raped and murdered a girl!”

From underground Soviet cartoonists to punk musicians pretending to eat toxic waste, we need the funny transgressors from time to time and should be wary of their establishment critics. Don’t pretend you haven’t thought the same thing.

—Todd Seavey is the author of Libertarianism for Beginners and is on Twitter at @ToddSeavey