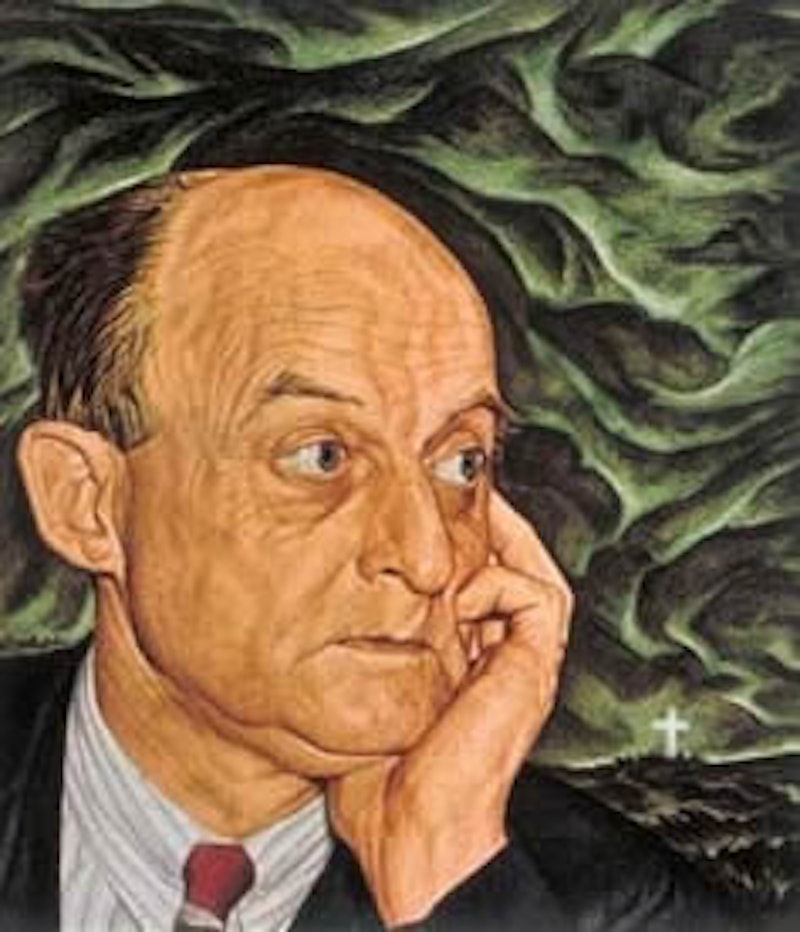

Why Niebuhr Now? asks John Patrick Diggins as the title of his brief, borderline hagiographic discussion of theologian Rienhold Niebuhr’s ethical and political thought. Why does everyone from Barack Obama to John McCain to Andrew Sullivan cite Niebuhr as an influence and an inspiration? Diggins’ answers are more or less what you’d expect—Niebuhr is profound, Niebuhr is thoughtful, Niebuhr’s analysis of power and evil and morality remains relevant.

All of which is no doubt true, but I wonder if Niebuhr’s ongoing popularity doesn’t rest on other sources. I think this passage from Why Niebuhr Now? is more to the point than Diggins quite intended:

Is the ethic of Jesus sufficient for mankind? It is noteworthy that Niebuhr’s own ethical teaching does not rely on it. Indeed, the theologian appeared at times compelled to remind the Savior not to forget that there is sin in the world… Niebuhr further diminishes the love ideal by suggesting in the politest terms that Jesus who died on the cross cannot be expected to offer useful instruction to humankind on how to live.

Niebuhr is a Christian theologian who believes that Christ is insufficiently realistic, and that those who follow Christ need to be taught “lessons about life.” In other words, he’s a Christian theologian who sounds like an atheist. In particular, he sounds like the atheist Nietzsche, who, Diggins says, Niebuhr read and appreciated.

The answer to “Why Niebuhr now?” therefore, could well be that Niebuhr is not all that Christian. In a secular society, a theologian of secularism is likely to be beloved. Certainly, as an atheist myself, Niebuhr’s skepticism of Christianity and tolerance of other viewpoints was one of the things I found most appealing in his writings. For example, in his essay “Can the Church Give a Moral Lead?” Niebuhr argued that Christians have no more access to the truth than anyone else—unless that access is the knowledge that they have no more access. “…the Christian faith gives us no warrant to lift ourselves above the world’s perplexities and to seek or to claim absolute validity for the stand we take,” Niebuhr maintains. Instead, Christianity “encourage[s] us to the charity, which is born of humility and contrition.” He concludes, “If we claim to possess overtly what remains hidden, we turn the mercy of Christ into inhuman fanaticism.” He drives this point home in “The Catholic Heresy,” in which he argues, “Nothing but embarrassment can result from the policy of commending Christ by pointing to the righteousness of the believers and the sins of the ungodly.” Christians are as much in need of repentance as non-Christians. All are steeped in sin.

Diggins argues that a consciousness of sin, and of human imperfectability, is at the heart of Niebuhr’s theology. This is so much the case that, as noted above, Niebuhr suggests that Christ himself did not take sufficient account of sin. Christ commanded human beings in this world to build their lives on love— a noble goal, but, Niebuhr says, not an actual possibility for sinful creatures.

For Niebuhr, sin is not primarily identified with desire, but with pride. Pride leads humans to believe that they know the mind of God and that they can perfect the world and themselves. It is pride that makes liberal reformers, Christian and otherwise, think that science and reason will solve the problems of inequality and prevent the misuse of power. It is pride that leads Christians to believe that they have the key to human happiness and salvation. And, conversely, it is pride that leads atheists to believe that, without religion, the world would be perfected. In what is perhaps Niebuhr’s most famous formulation, it is pride that leads to pacifism.

Pacifists, Niebuhr argues in “Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist,” have:

absorbed the Renaissance faith in the goodness of man, have rejected the Christian doctrine of original sin as an outmoded bit of pessimism, have reinterpreted the cross so that it is made to stand for the absurd idea that perfect love is guaranteed a simple victory over the world… This form of pacifism is not only heretical when judged by the standards of the total gospel. It is equally heretical when judged by the facts of human existence.

The last two sentences are quintessential Niebuhr. Christianity for him is not a challenge to “the facts of human existence,” but a profound description of them. It is not a utopian vision, but a chastening of utopian visions. Humans are flawed, but their own false pride tells them they can control destiny and achieve happiness. Christianity is the path to humility, because it knows that power, pride, and sin are humankind’s lot on earth.

Niebuhr’s philosophy is convincing; he’s a thoughtful, profound thinker, and his warnings about utopias, fanaticism, and modernity’s delusions of perfectibility remain relevant and telling. But when I see the eagerness with which he’s embraced by Neocons or Barack Obama, I wonder if his theology is really quite as opposed to pride as Diggins insists. Not to impugn Obama, but anyone who gets his butt behind the desk in the Oval Office is unlikely to be overly afflicted with humility.

In fact, I think that, despite pointing out the mote of pride in his neighbor’s eye, Niebuhr has a beam or two in his own. After all, you’ve got to have a fairly high opinion of yourself to tell God he doesn’t understand sin. Niebuhr saw clearly the pride inherent in optimism and utopian perfectionism. But he was less aware of the pride of pessimism and, indeed, of realism. Understanding the dirty, dark secrets of how the world works, understanding the ubiquity of power and the corruption of your fellow human beings—there’s a rush there, as there always is in being the one-who-knows. Obama can have a tragic sense of the limitations of humanity and of the inevitable imperfect consequences of his actions—and with that sorrowing Shakespearean insight, he can drop bombs on Libya and shake his head sadly at those who critique him for failing to understand the necessary compromises of power. Is that really less egotistical than George Bush exclaiming “Hyuk! Axis of Evil!” and sending the planes into Afghanistan? And, if we’re going to talk about pragmatic realism, what practical difference does it make exactly to the folks on the ground that they’re being bombed by a chastened realist rather than by a vaunting idiot?

Everybody complains about the religious right, but the real religion in America today, the faith of our rulers, is not in Christianity or utopia. It’s a faith in reality and pragmatism. If we only look at the world clearly, these rulers tell us, without rose-colored glasses or unnecessary ideological baggage, we can manipulate results in a bipartisan fashion approved by experts and arrive at solutions that, while not ideal, are the best that can be hoped for. Faith, hope and love allow us to better appreciate and tolerate the painful necessities of our pragmatic decisions. They certainly don’t challenge us to question those necessities. There are no miracles, which is another way of saying that we know how the world works.

Jesus died on the cross to tell us to carefully weigh power relationships and choose the least bad option. That’s a moderate, non-utopian message that technocrats can get behind. Which perhaps explains “Why Niebuhr now,” and why Niebuhr later, and why Niebuhr as long as serious people want to tell themselves they are behaving seriously when they exercise power, tragically or otherwise.

—Noah Berlatsky can also be found at hoodedutilitarian.com