Need any more proof that New York City’s a strange and occasionally confusing place, that it can baffle anyone looking for common sense in urban planning, or a place that can give urban explorers fits of head-scratching? Take a look at Edgemere on the Rockaway peninsula in the Beach 30s and 40s streets, whose mile after mile of ocean beach front has been left to rot.

Edgemere, at least in the part of it south of the elevated, presents what appears to be a developer’s dream: an endless vista of sea and sky along the Atlantic Ave.; south of here your next landfall is Central America. In a sane world, it’d be lined with parks and nature trails, or amusement areas rivaling Coney Island, or gambling meccas like Atlantic City. Instead, this is reality in Edgemere.

Sand dunes, weeds and unwired telephone poles punctuate Edgemere south of the elevated subway, with high-rise developments in nearby Far Rockaway looming in the distance. A century ago Edgemere’s streets were lined with beachfront hotels and more modest houses and bungalows. In 1892, Frederick J. Lancaster, heading a group of investors, purchased a wind-whipped, barren stretch along the Rockaway peninsula just west of Far Rockaway. At the time, ironically, it was just as empty as it is today with the exception of an artificial canal, Norton’s Creek, that bisected the region.

Lancaster opened the Edgemere Hotel at Beach 35th St. in 1895. A clue about why Edgemere has fallen into disuse can be obtained from the story of the lavish hotel, which was buried under tons of sand from a big storm that struck just one year after the building opened. It reopened the next year after two bulkheads were built and Norton’s Creek was drained.

Though Edgemere (whose name means at the sea’s edge) was downplayed for the most part as a seaside resort area, with most summer vacationing areas concentrated in Far Rockaway, the majestic Hotel Lorraine was constructed at Beach 36th St. and Sprayview Ave. by Henry Holt in 1908, featuring a telephone in every room, a dance band and golf, and by 1910, electric elevators and hot and cold running water, all of them innovations at the time. This photos above were taken in. Robert Moses tore down the Lorraine in 1941 for a parking lot, itself now under sand and weeds.

The Long Island Rail Road arrived in Edgemere in the 1890s, with stops at Wavecrest (Beach 25th), Edgemere (Beach 36th), Frank Avenue (Beach 44th), Straiton Avenue (Beach 60th) and Gaston Avenue (Beach 67th). The line ran at grade between Edgemere Avenue and Rockaway Beach Boulevard until 1942, when it was elevated along a lengthy concrete elevated trestle with a new roadway, Rockaway Freeway, constructed beneath it. After a fire destroyed a LIRR bridge in Jamaica Bay in 1950, the NYCTA purchased it for $8.5 million and then ran subway service along the line beginning in 1956 (though it cost a double fare until 1975, when the fare was raised to 50 cents). Above is the Edgemere LIRR stationhouse in 1914.

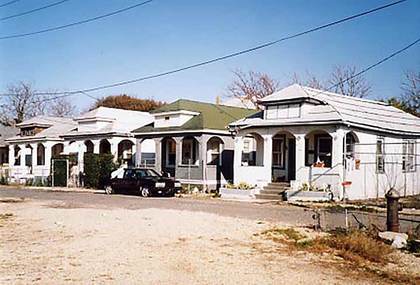

In the early 20th-century Edgemere developers concentrated more on residential living than on resorts or amusement areas, though there were oceanside hotels like Norton’s Half-Way House at Frank Ave. (halfway to Far Rockaway we presume) as well as the Belvedere, Frontenac, Coronado, and Shelbourne. Street after street was filled with cottages catering to summer boarders. However, there were more permanent residences built like the ones above left, on Frank Ave. (Beach 44th). Note the open porches and numerous windows from the pre-air conditioned era.

Though the Edgemere bungalows were plowed under long ago, some surviving examples can be spotted throughout the peninsula, especially in a concentrated area from Beach 25th-28th Sts. south of Seagirt Ave. This fast-disappearing enclave was featured on the PBS special A Walk Through Queens with David Hartman and Barry Lewis, and the homeowners have their own organization, the Beachside Bungalow Preservation Association. Seen here are bungalows at the south end of Marvin St., near the boardwalk.

Can Edgemere be brought back south of the el? Various plans exist, most of which call for residential development. This should be an amusement area, a playground, a place for sea, sun and sand. If Atlantic Beach and Long Beach, which aren’t very far away from here, can be summer spots, so can Edgemere. It has subway service that can feasibly be converted to a super-express from Manhattan or Brooklyn. Unlikely NYC neighborhoods have made comebacks, like the meatpacking area in the Village and Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Those, however were brought back by trend-seekers; they came and stayed, bringing unaffordable housing costs with them. Seaside development should be done without the privileged few occupying the shoreline and leaving out the less lucky.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)