Nobody has done a good enough job explaining why, in Back to the Future, Marty McFly starts disappearing from his family photo. Here’s the setup: unless Marty—while stranded in the world of 1955—manages to introduce his parents to each other, he’ll disappear from the photo, and the world, for good. He’s interrupted a sequence of events leading up to his own birth, and only he can heal the breach.

Consider: if the future was really that fragile, then nothing Marty did could ever have restored anything. Reality would just give up and go to pieces. Furthermore, the countdown is a bizarre form of mercy. Marty has enough time to take action, since he’s disappearing slowly, instead of doing the logical thing and just blinking out of existence all at once.

In short, the physics won’t wash. Every plot hole is a giant invitation to look elsewhere for the raison d’être.

As millions know, Marty saves himself by going to a dance his (future) parents are attending. His initial plan, which involves making advances on his mother, falls short. He then runs onto the stage, seizes a guitar, and invents rock ’n’ roll on the spot, generating enough heat to glue his mother and father together on the dancefloor. Just like that, Marty’s future snaps back into place.

It’s now my duty to inform you that all of the events I’ve just described are unbelievably Freudian. Marty’s attempt to force himself on his mother, even as a ploy, is a clear replay of an infant’s Oedipal love affair with his mother during the period when the infant views his father as a rival for her affection. Marty’s plan, of course, is then disrupted/carried out by his evil twin, Biff the rapist. Marty’s gradual “disappearance” is the opposite infantile response: neurotic guilt. Marty’s castrating himself—his limb mysteriously “vanishing” of its own accord—to get rid of taboo desires. The musical performance, conversely, is (at last!) the mature act of a young man who accepts sex as a universal, and concedes the sexual relationship between his parents.

Whenever Freudian readings like this one go to print, they suffer most from their own correctness. They make art seem like a sad standard-bearer for outdated psychological theories. It’s Robert Zemeckis’ movie, and he can make Marty come on to his own mother, just like he can make cars fly backwards and forwards through time. All it proves is that believing in Freud is like trying to run a car on plutonium—see how far that gets you in real life, friend-o.

Moreover, Freud’s sexual obsessions tend to pre-empt other thoughtful readings. What if the real meaning of the film lies in Marty’s attempt to come to terms with his own radical contingency—the fact that, except for a tawdry series of accidental events, he wouldn’t exist. By playing “Johnny B. Goode,” Marty affirms his own reasons for existing, in defiance of a universe without purpose or design.

That song, “Johnny B. Goode,” is still undeniable. The adrenaline rush of listening to it hasn’t diminished at all, which is how just one oldie manages to propel Back to the Future to its climax. What makes “Johnny B. Goode” so deathless is, ironically, its place in history. The song celebrates the birth of a new profession: the rock ’n’ roll star. It pushes Chuck Berry’s electric guitar to the wailing edge of over-amplification. The vocals are shouted, and sung, and that internal tension lets us actually hear that the shouting is a novel and reckless thing to do. Like all great works of art, “Johnny B. Goode” is both of its time and ahead of it. It’s the prison and it’s the jailbreak. To listen to that song is to experience it not only as a product, finished and complete, but also to hear Berry kicking over the traces in 1958.

Back to Freud and Oedipus. In his great work Structural Anthropology, Claude Levi-Strauss tackles the story of Oedipus from the standpoint of myth. The Oedipus story deals, he claims, “with the inability, for a culture which holds the belief that mankind is autochthonous… to find a satisfactory transition between this theory and the knowledge that human beings are actually born from the union of man and woman.” The word “autochthonous” is opaque there, but all Levi-Strauss means is that the Greeks felt human beings were something unprecedented, unlike the rest of creation. Thus they ran into a chicken-and-egg problem: if all children are born to parents, how could the miracle of humanity have ever taken place?

The Oedipus myth doesn’t solve this problem; that’s not its function. Its function, rather, is to articulate what problem the Greeks are trying to solve: when Oedipus runs into the Sphinx, and realizes that the answer to the riddle is “man,” he awakens. He becomes aware that the question of his origins, as a man and a human being, is the most important unknown in his life.

The reason that a Freudian reading of Back to the Future feels pat and irrelevant is that when it came out, in 1985, Zemeckis was already well sick of purely interfamilial dynamics. The nuclear family was an anti-historical fiction designed to insulate postwar Americans from any sense of their place in the larger world, which is why its apotheosis (in the 1950s) was coeval with the Red Scare. The mess that young Marty is really trying to clean up involves terrorists, plutonium, and technologies that endanger the entire planet. Like Marty, we may owe our existence to past accidents and errors, but that’s no reason to ignore lessons buried in the past. (When Doc finally heeds Marty’s frantic advice and puts on a bulletproof vest, it saves his life.) The question Zemeckis asks us, as Levi-Strauss would put it, is what it means to be an American—now, in 1985. His film raises the possibility that the best things about being American may vanish if no answer is forthcoming soon. That’s why, near the end of the movie, Doc is screaming at Marty that the problem “is your kids!”

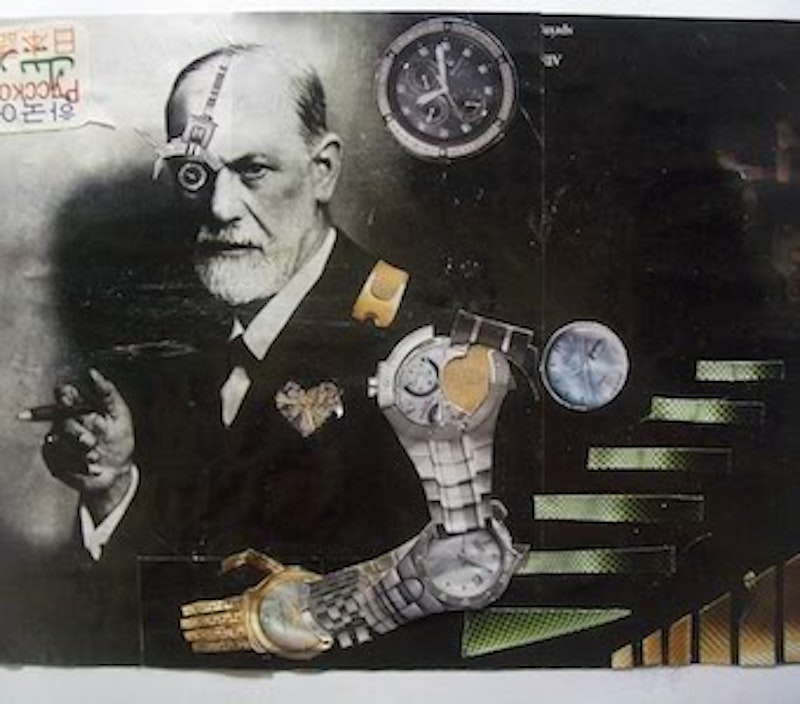

And so it is, when we consider Sigmund Freud, that we have to place him in his own historical moment as well. Freud would’ve been glad to be wrong about this or that feature of infantile development, female sexuality, or dream-logic. The value of his work can’t be estimated by uprooting his hypotheses and judging them by our current assumptions. Reading Freud, one observes a man largely baffled by clinical phenomena, frustrated by the shackled discourses of Victorian psychology, and eager to discover and codify a scientific method of some actual use to his patients. Freud without his doubts, his compassion, his revisions and enigmas, is of no use whatsoever. His veracity on any specific psychological point is arguable. But without him, I would never have wondered why Marty disappears so slowly, or why Chuck Berry still sounds fresh, or whether Biff might be a projection.

Because Freud’s there, perpetually trying to unriddle us, there are stubborn, Freudian questions we feel duty-bound to answer. If however we let him disappear, on the grounds that he has been “disproven,” such questions will cease even to be asked. I can’t look gladly upon losing so much light.